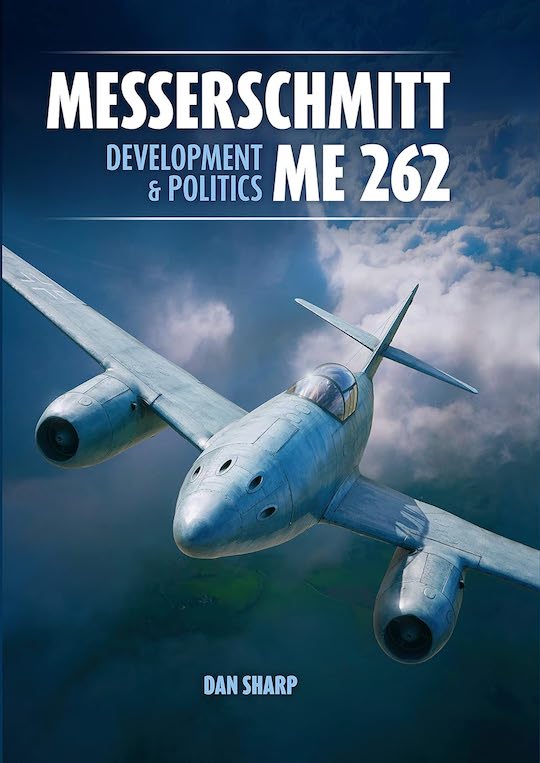

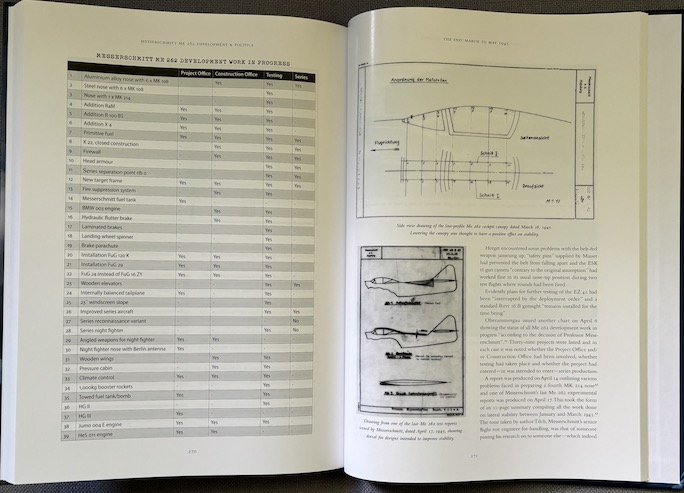

Messerschmitt Me 262: Development and Politics

by Dan Sharp

by Dan Sharp

“The Over-All-Report states that Germany’s ‘inability to bring the [Me262] into operation in any appreciable numbers can be attributed in a considerable degree to the failure of the German Air Force and the Air Ministry in their planning and judgement, and to political intervention into the purely technical fields of aircraft production and tactical disposition of operational aircraft. To this can be added the effects of our strategic bombing on Me 262 production, our low-level attacks on completed aircraft and the German inability to solve completely the technical problems inherent in turbojet propulsion design.’”

Is the dense prose making your head spin already? The excerpt is from an appendix to a 1947 report by the United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Aircraft Division. By virtue of being the first official and comprehensive assessment it became the foundational document of just about everything written in later years, which also means that whatever flaws and bias it contained would become enshrined in the literature. Unless . . .

Unless you are British historian/journalist/editor/writer Dan Sharp, someone who is clearly able to practice independent thought instead of merely parroting other voices. He reviewed thousands of archival documents and thus his resulting book “owes little or nothing to earlier works on the same subject.”

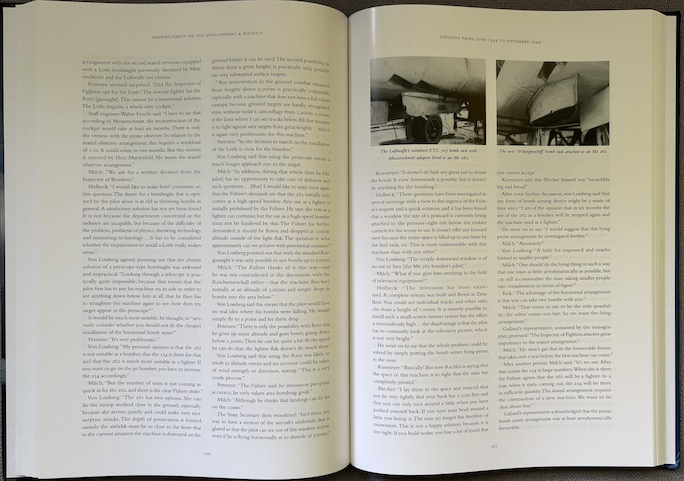

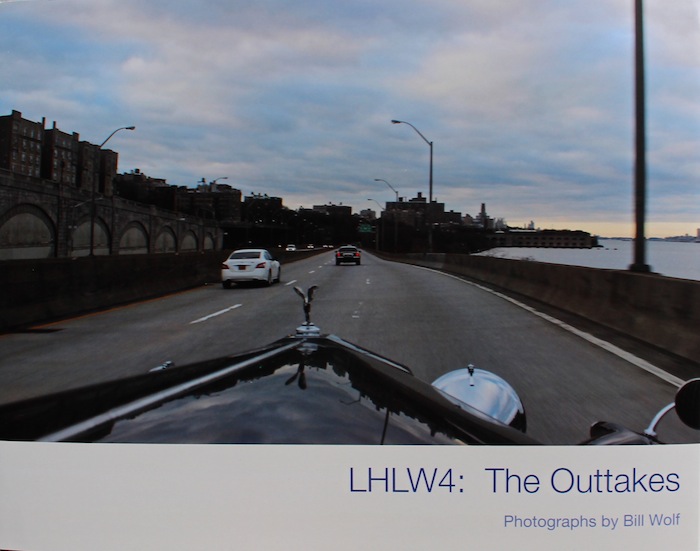

There are stacks of books about this aircraft so why would you need another one? Because this one tells a different story, and it handles the telling of the story differently. Also, precisely because of the second item, this is probably the one book—provided you have the discipline to read if front to back and line for line instead of skipping around—that will give you a sense of having earned whatever you learned. The reason for that is that Sharp draws on innumerable first-person quotes, excerpts from preserved or published primary sources, and even transcripts of actual dialog (sometimes pages long) from meetings and the like but—and this is where you have to work for it—rich as this material is, a dizzying amount of opening and closing quotes are your only “stage direction” for following the plot. Miss one quotation mark, and you are immediately in the weeds (see the following photo). Researchers will note with approbation that sources for much/most of this material is given in the Endnotes, albeit in a frustratingly small type size (even so, they take up 14! pages).

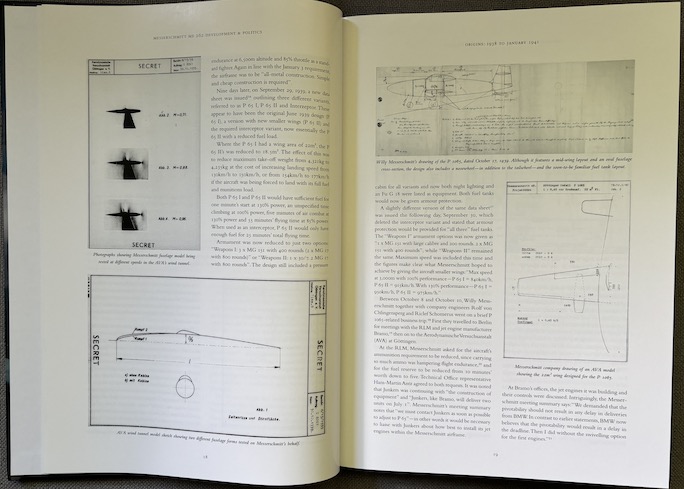

You won’t be able to see it at this size but these pages are one example of basically back to back quotes and transcribed dialog, each marked by opening/closing quotes, sometimes with the author’s connective text interspersed. In the case of paragraphs-long excerpts there will of course only be an opening quote at the start of a new paragraph, and the only point in showing this spread is to illustrate the point about not letting your attention wander.

Everything in that intro quote above is what has become shorthand for what the Me 262 did do and failed to do. Sharp’s reading does not lead him into a different direction but to the realization that of all the stakeholders—on the one hand united in their desire to win the war but on the other hand obligated to also look after their own internal needs and priorities—only Messerschmitt can be said to have achieved their goals.

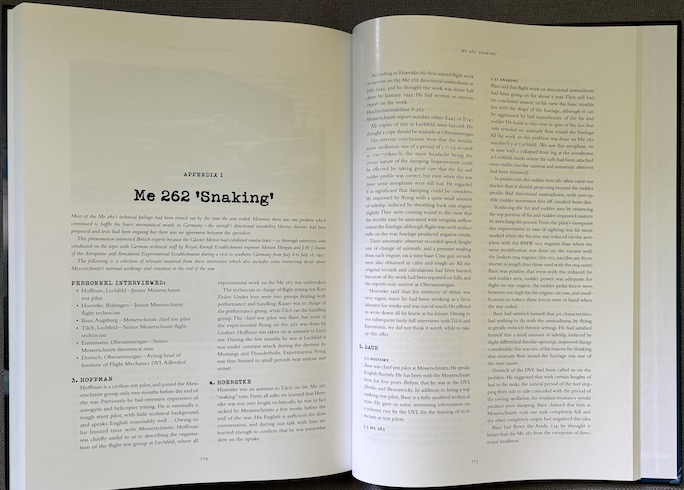

“Directional instability” remained one of the last technical failings, “baffling the finest aeronautical minds in Germany.”

Whittling away at that argument, the book’s main focus is on the airframe and not the engine because that came from another firm (Junkers). When all is said and done, the book is “a cautionary tale about the attempted introduction of radical technological change in a time of national crises.” What will probably surprise readers is that Messerschmitt’s very success in developing this radical new technology meant they had to cannibalize resources from their other, also successful, aircraft lines and ongoing Me 209 and 210 research. Robbing Peter to pay Paul as it were, clearly a dilemma for the people who are just trying to keep the lights on.

As if the technical and logistical issues (retooling factories, training pilots on twin engine aircraft, service/maintenance procedures, lengthening runways etc etc) aren’t formidable enough, Sharp points to the Meddler in Chief’s “unnerving tendency towards micromanagement in areas where he lacked even the most basic technical knowledge” as the key reason why the project, once begun, then ended up for 2 1/2 years—in other words, half the war—in a “drift” because no one was clear if the Me 262 was to be a fighter (day? night?) or a bomber or a recon aircraft, or even a jet.

After a quick dip into jet engine work in Germany the book begins with the commissioning of the aircraft in the summer of 1938 and, in chronological order, goes to the end of the war in May 1945. Supported by archival documents, technical drawings, and photos the book examines all relevant technical and performance aspects. Anybody who has ever attempted to make an aircraft fly, even a paper one, will realize that you absolutely must know where the airframe’s center of gravity is going to be—which means you need to know what shape the engine will be and where it will be mounted, which means the engine maker needs to know first of all what this aircraft is supposed to do. Even if you are not an engineer you can see the problems here, and this book is a very useful case study. Good reference is made to concurrent aircraft like the well-established single-engine piston Bf 109 and FW 190 and their planned successors, and the book makes ever more clear how the changing tactical and strategic picture crippled whatever role the Me 262 could have played.

After a quick dip into jet engine work in Germany the book begins with the commissioning of the aircraft in the summer of 1938 and, in chronological order, goes to the end of the war in May 1945. Supported by archival documents, technical drawings, and photos the book examines all relevant technical and performance aspects. Anybody who has ever attempted to make an aircraft fly, even a paper one, will realize that you absolutely must know where the airframe’s center of gravity is going to be—which means you need to know what shape the engine will be and where it will be mounted, which means the engine maker needs to know first of all what this aircraft is supposed to do. Even if you are not an engineer you can see the problems here, and this book is a very useful case study. Good reference is made to concurrent aircraft like the well-established single-engine piston Bf 109 and FW 190 and their planned successors, and the book makes ever more clear how the changing tactical and strategic picture crippled whatever role the Me 262 could have played.

At a low $55 MSRP this splendid 8.5 x 12” hardcover puts to shame other publishers who struggle to put a meagre softcover together; it is printed on good paper, extensively illustrated. and has an exemplary apparatus (7 appendices, endnotes, bibliography, index). Also praiseworthy: nary a typo in sight despite the many, many German words.

The same author/publisher already dealt with this subject as part of their “Secret Projects of the Luftwaffe” series, in 2020 (ISBN 978-1911658085) as Vol 1 Jet Fighters 1939–1945; and in 2022 (ISBN 978-1911658276) as Vol 3 Messerschmitt Me 262: Development and Politics which is basically a first edition of the version reviewed here.

Copyright 2024 Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter