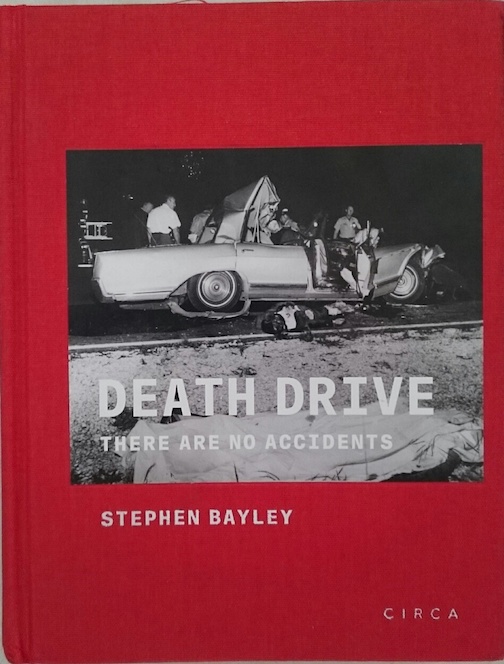

Death Drive: There are No Accidents

Is it possible to write a book about fatal car crashes without being morbid, crass or tasteless? Before I read this book my answer would have been in the negative but, after enjoying every one of its 230 pages, I have to tell you that my reservations were unfounded.

As you would expect from a former director of London’s Design Museum, Stephen Bayley not only has an acute perception of the zeitgeist but also writes with an endearing effervescence and brio. He is knowing and wry but also acutely respectful of his subjects who range from the predictable James Dean and Isadora Duncan to the less expected General Patton and Jackson Pollock. Bayley writes about twenty fatal accidents in all, with the introductory caveat that “Had Volvo patented the three point seatbelt in 1927, instead of 1959, this book would have looked rather different.” Although his reasons for doing so are not entirely convincing, I was nevertheless relieved to see that Princess Diana’s fatal crash in 1997 was not included; so seismic an event was it (even to this borderline Republican) that the space it would have merited would have disturbed the balance of the book.

As an object to touch and feel the book is exquisite, with a heft its modest price belies. Bound in cool red and black, the front cover features a glued-on black and white picture of Jayne Mansfield’s wrecked Buick Electra 225, a car possessing what Bayley terms “cetacean elegance.” Potential buyers will certainly be left in no doubt as to the subject matter. . . . The book comprises a five- or six-page biography of each victim, the circumstances of the crash, and a discourse on the vehicle involved with the start of each chapter being punctuated with a pointillistic black and white portrait of its subject.

As I read the book I was reminded how often death can add an unimpeachable punctuation mark, often an exclamatory one, to a career that might have been waxing like James Dean’s or waning like Marc Bolan’s. Would we feel the same about the genius of Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, or Jim Morrison if they were now just washed-up has-beens on daytime TV instead of shining in the eternal lustre that membership in the 27 Club bestows? Bayley describes how the criteria for inclusion comprised the “pattern of elegy and absurdity that is recurrent here,” building on Albert Camus’ apercu that there can be “nothing more absurd than to die in a car accident.” Which, of course, is precisely what happened to Camus, having met his ironic demise in that most stylish of French cars, the Facel Vega HK500.

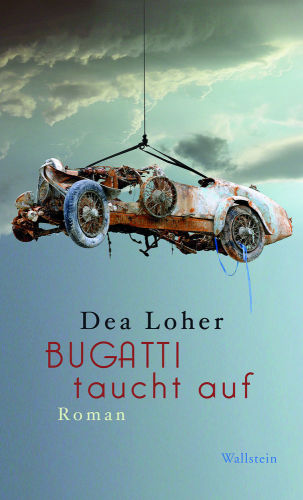

I appreciated the rigour Bayley applies to his subjects and I suspect I won’t be the only reader who learns that the conventional narrative of many fatal accident stories is quite wrong; Isadora Duncan did not die in a Bugatti after all but in a rather more humble Amilcar driven by one Benoit Falchetto, a man who worked for Bugatti as a salesman-mechanic and who was nicknamed “Buggatti” (sic) by his passenger. Bayley writes that “her final career arc, wrenched by great force from car to sidewalk by unforgiving silk, was the most dramatic Isadora Duncan move of them all.” I just had to smile at that, even if there might have been a scintilla of guilt for having done so. . .

The incident that killed General George S. Patton in 1945 was, as Bayley puts it, “the result of a low speed crash in suburban Mannheim” and was rendered all the more extraordinary because Patton was the passenger in a seven-seater Cadillac 75, a vast machine that looked impregnable. With his customary elan, Bayley comments that it was “so pitiful an irony that the hinterland of the accident has excited wild speculation , becoming a locus classicus of the demented fabulism that is now known as ‘conspiracy theory’.” Chief suspects ranged from the Russians to Eisenhower via “dark forces”—in other words a perfect example of how, no matter how clear a fatality’s causation may be, the more famous the victim the less inclined the public is to accept it (see also Elvis Presley and, of course, Princess Diana) .

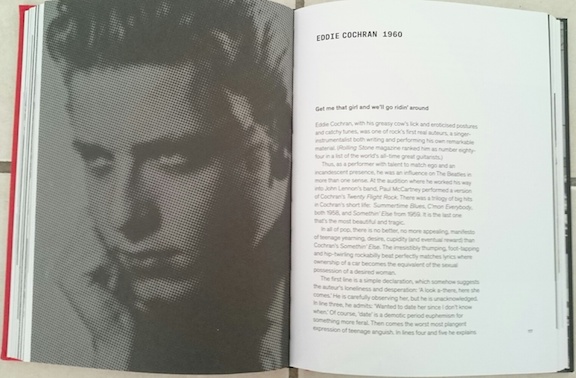

Rock n’ roll notoriously has a long roll call of the prematurely departed, from Buddy Holly and the Big Bopper in 1959 to John Lennon in 1980 to Amy Winehouse in 2011, and Bayley includes accounts of both Eddie Cochran’s death in 1960 and Marc Bolan’s hideously mundane shunt in a Mini 1275GT in 1977. Cochran’s demise has an eerie subtext; Bayley deconstructs the lyrics of Somethin’ Else, the song he describes as “a manifesto of teenage yearning , desire (and ) cupidity,” and reflects on the singer proclaiming his ownership of a car at last, even if it was “just a forty-one Ford, not a fifty- nine.” And Cochran died in a fifty-nine Ford, if not the Thunderbird or Galaxie Sunliner he was probably yearning for in the song. Instead, it was a Ford Consul Mark II, a lame UK Ford saloon with stylistic cues from both Thunderbird and Fairlane, and it was driven by a taxi driver in Chippenham, Wiltshire, a very long way from Cochran’s native Minnesota.

Amongst the car enthusiast community there is often a tendency to deprecate the amount of primary and secondary safety systems in the modern motorcar. These might include ABS which triggers prematurely, TCS which inhibits oversteer tomfoolery, or the host of complex and sometimes weighty secondary systems such as airbags or strengthened A, B and C pillars. Having read Death Drives I am left reeling at the minor nature of so many of the fatal accidents that nowadays might only be routine “fender benders” with no greater injury than hurt pride. Cars such as Nathanael West’s 1940 Ford Super De Luxe Woodie that crashed en route to Scott Fitzgerald’s funeral, or Porfirio Rubirosa’s 1959 Ferrari 250 GT cabriolet are damaged seriously enough to be undriveable but from a 21st Century perspective it seems inconceivable that their occupants would not have survived. Yet again we are reminded of LP Hartley’s words that “the past is a foreign country, they do things differently there.”

Should you buy this book? I think you should—it is beautifully written, wryly amusing and, actually, not all macabre. Like it or not, the importance of the fatal car crash in modern popular culture cannot be denied, featuring as it does in works as disparate as J.G. Ballard’s Crash and Grace Jones’ Warm Leatherette, but nobody has analyzed its relevance quite so shrewdly and entertainingly as Stephen Bayley in Death Drive.

Copyright 2016, John Aston (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter