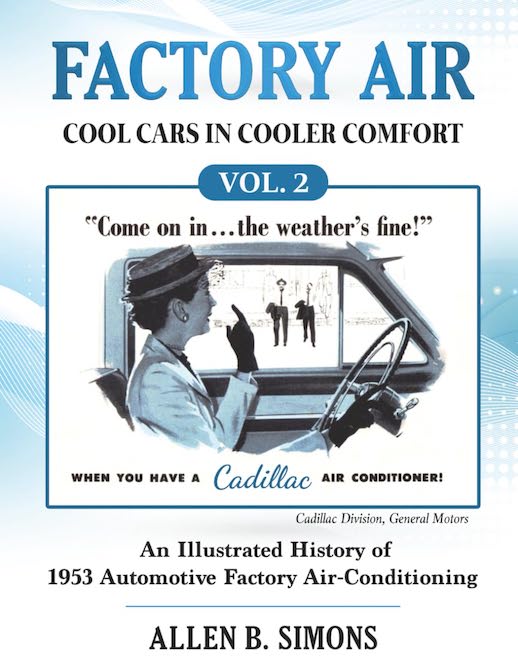

Factory Air: Cool Cars in Cooler Comfort, An Illustrated History of Automotive Factory Air- Conditioning, Vol 2, 1953: The Magical Year

by Allen B. Simons

by Allen B. Simons

“Currently taken for granted as standard equipment, the road to cool, dehumidified driving deserve scrutiny of Detroit’s 1953 introduction, its first mass-produced air conditioning, some 70 years ago.”

It is easy to understand why Allen Simons subtitled this second volume of his Factory Air book The Magical Year because 1953 was the year air conditioning in automobiles truly came into its own. Every major manufacturer offered—and advertised—models that could keep driver and passengers calm, collected, and cool on the hottest or most humid days. GM’s Cadillac, Oldsmobile, and Buick, Chrysler’s Custom Imperials, De Sotos, and Dodges, Ford’s Lincoln division, and Packard all vied for the attention of buyers who desired this new luxury and comfort—and were willing and able to part with the not insignificant amounts of money.

This volume was originally intended to publish the year following his first volume, meaning 2024. Well, sometimes life gets in the way of best intentions. That’s precisely what occurred for Simons and his family, delaying the publication of this second volume. In fact though it bears a 2025 publication date, it’s only becoming generally available as 2026 dawns. That said, it’s worth the wait.

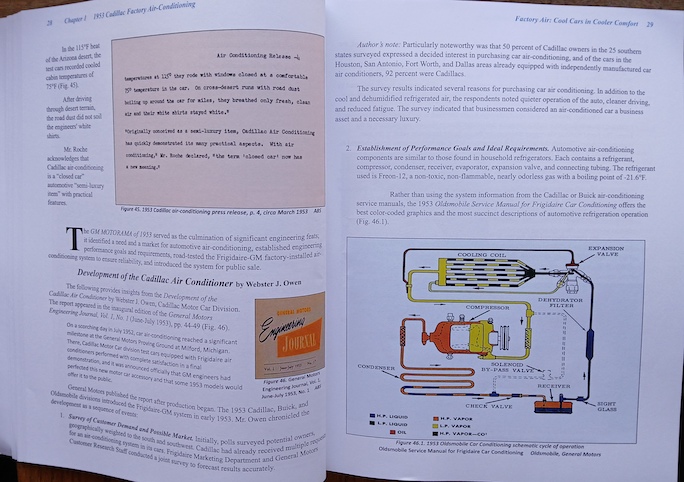

Of particular interest are the dozen pages Simons devotes to the content of Vol 1, No 1 of GM’s Engineering Journal in which Cadillac engineer Webster J. Owen details all the testing conducted to optimize air conditioning function in an automobile. The operating cycle schematic is bottom right.

The first chapter provides a thorough and detailed explanation of the inner workings of GM’s Frigidaire Division’s a/c system and that of each individual component drawing from an SAE paper and the training and service bulletins used to train dealership service personnel. These are all Cadillac applications noting that deviations, made by and used by sister divisions Buick and Oldsmobile, will be noted in the two following chapters.

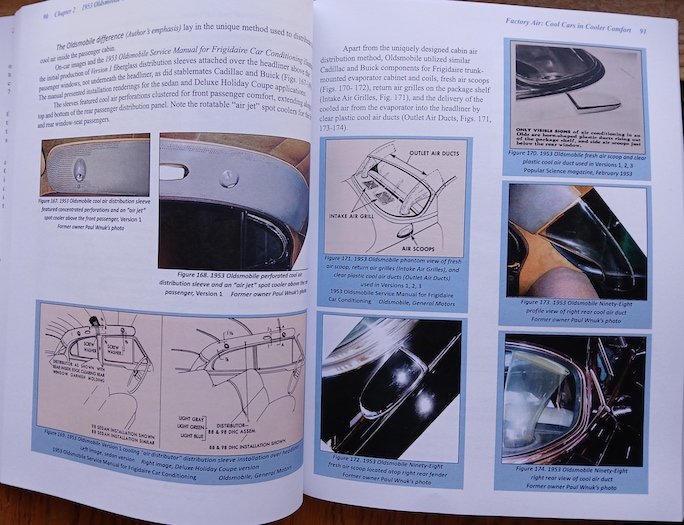

The second chapter focuses on Oldsmobile. It made running changes in the method the cooled air was distributed. Initially air came through honeycombed perforations overhead with spot points via air-jets to targeted areas. The second version replaced the perforations with metal grilles. The third version replaced the single-speed fan with a two-speed controlled by a switch on the dash.

Oldsmobile experimented with different types of air distributions with several illustrated on this page pair.

The next chapter presents Buick’s approach to air conditioning its cars but I chose to temporarily skip ahead three chapters to read what Simons found and had written regarding Packard simply because that company had had no prior in-house engineering experience. Packard had contracted and bought units from Bishop and Babcock for its 1940-41-42 models. For ’53 and ’54 models, it outsourced to GM’s Frigidaire, purchasing 500 units.

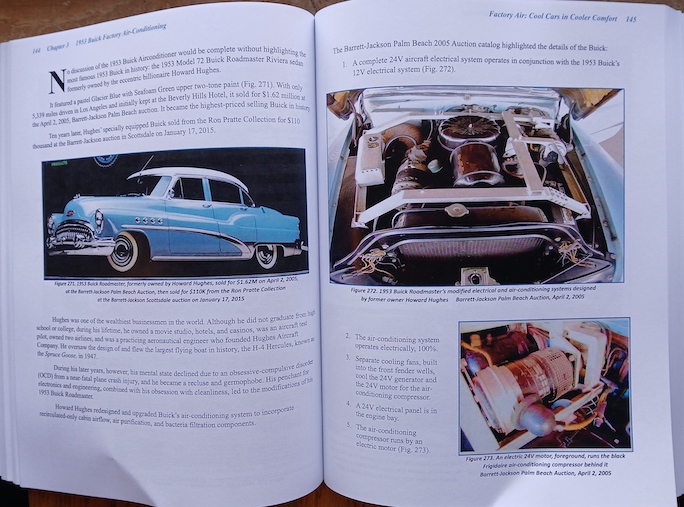

Turning back to read the Buick chapter, as with its sister divisions because air conditioning was so new, it produced several publications to inform and educate the public and its service people. Pages from each are reproduced. Then one of the cars profiled features modifications its owner caused to be done. That owner was the reclusive Howard Hughes who “redesigned and upgraded Buick’s air-condition system to incorporate recirculated-only cabin airflow, air purification, and bacteria filtration components” in his Roadmaster.

As he aged Howard Hughes became more reclusive and germophobic. He caused his ’53 air conditioned Roadmaster to be altered to include bacteria filtration and air purification as shown on these pages.

Chrysler Corporation called its a/c Airtemp developing it from the office air conditioning in operation in its NYC Chrysler building. Its 1953 advertisements claimed it was “the highest capacity system on the road . . . cooling faster than any other system.” As with telling of the other makers’ programs, Simons reproduces both advertising and factory publications to explain Chrysler’s approach as he identifies the Chrysler products for which air conditioning would be offered; its Imperial car line, De Sotos, and Dodge Coronets.

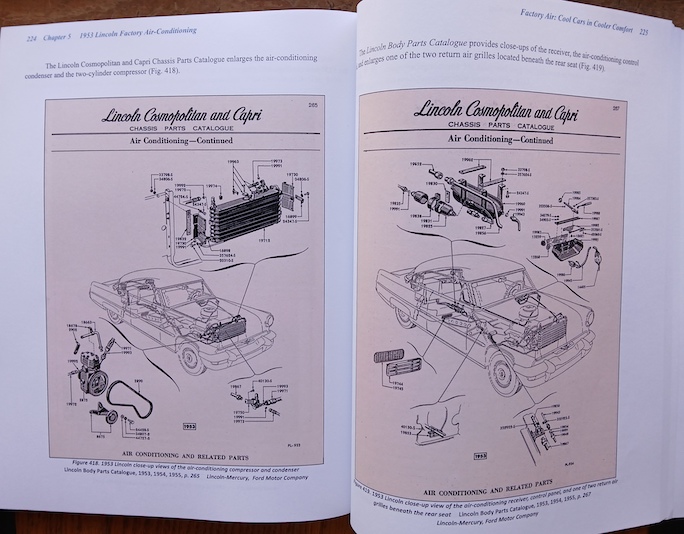

Ford was late introducing air conditioning as it was June 1953 before it even announced air conditioned Lincolns to its dealers telling them “It will require a year-round selling effort.” Each of the chapters—except that covering Ford/Lincoln—concludes with a few pages showing a real car, sometimes two, showing a real car equipped with what has been discussed. Each of these examples Simons had found and inspected with his eyes, hands, and camera.

Pages from a Lincoln Body Parts Catalog detailing its a/c application.

The very last pages are statistics recording information such as the number of vehicles sold with air and what percentage that was of total sales. Prices and other details are included as well. These statistics are supported and reiterated on additional pages at the end that I’d readily identify as appendices although Simons doesn’t specifically identify them as such.

Simons projects his third volume will publish Spring 2027. He plans to include the two cars—one from Pontiac, the other from Nash—as each introduced outlet vents up front located behind the dashboard. It will cover air conditioned cars offered to the buying public during the three years 1954, 1955, and 1956.

Copyright 2025 Helen V Hutchings (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter