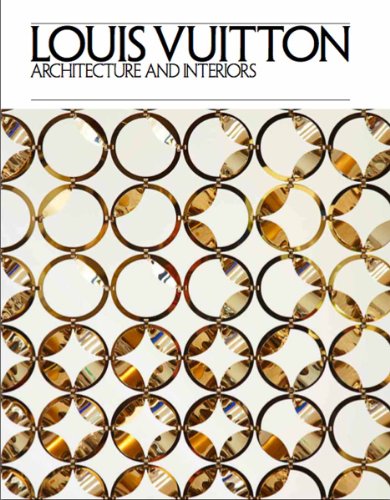

Louis Vuitton: Architecture and Interiors

by Frédéric Edelmann, Ian Luna, Rafael Magrou, Mohsen Mostafavi

by Frédéric Edelmann, Ian Luna, Rafael Magrou, Mohsen Mostafavi

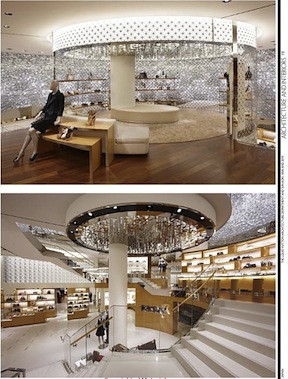

“Form follows function” is the axiom of architectural design in the modern era. Simply said, the design of an edifice is based upon the purpose it will serve. One trajectory of this axiom led to the array of glass monoliths that characterized much of 20th century urban architecture. However, another trajectory has evolved to recognize that how function is defined will cause the form to deviate significantly from orthodox trends of minimalism in design solutions. An example of this trajectory is when commercial aspects of “dazzle” and “brand resonance” become part of the function. This book sets out to document and illustrate the effort to marry one of the most recognizable brands of high fashion and style (Luis Vuitton) with the architecture and design that was created to resonate with their brand.

To tackle the subject, credit is given to four authors, each with an illustrious background to qualify their contributions, but, according to biographies included in the text, only Mostafavi is an architect as well as the Dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Design. Mostafavi also writes the Foreword, which almost sets juxtaposition between orthodox architectural design and the exploration of Luis Vuitton’s in-house architectural department and the associated architects that are behind the twenty-seven projects and proposals covered in the book. Biographies of each of the architects associated with the projects are provided as well.

The projects cover the globe; each is presented by territory, as a case study, covering the various aspects that challenged the final designs, since projects for public, commercial or industrial use ranged from complete site development to adaptive design that would have to conform to the space to be used and the building codes that would protect various aspects of development, including historical building preservation. In addition to the case studies, there are interviews, an essay by Mostafavi and an examination of the treatments for textures, façades and signage. What may be missing in the content is direct sourced commentary from the greater architectural world in critique and/or support of the various projects’ results. Awards won by the architects (including awards for LV project) are noted in the respective biographies.

The projects cover the globe; each is presented by territory, as a case study, covering the various aspects that challenged the final designs, since projects for public, commercial or industrial use ranged from complete site development to adaptive design that would have to conform to the space to be used and the building codes that would protect various aspects of development, including historical building preservation. In addition to the case studies, there are interviews, an essay by Mostafavi and an examination of the treatments for textures, façades and signage. What may be missing in the content is direct sourced commentary from the greater architectural world in critique and/or support of the various projects’ results. Awards won by the architects (including awards for LV project) are noted in the respective biographies.

There is no shortage of lush photography, illustrations and floor plans, making the book also work well as a coffee table book with its 9½ x 12¼ dimensions. There is a section that gives credit to those that made each of the projects possible as well as crediting the illustrations, but there is no index and, given the format of the content, one is not missed. While this review is based on only a digital version of the book, the publisher is Rizzoli, renowned for its high quality in the fine printing market.

There is no shortage of lush photography, illustrations and floor plans, making the book also work well as a coffee table book with its 9½ x 12¼ dimensions. There is a section that gives credit to those that made each of the projects possible as well as crediting the illustrations, but there is no index and, given the format of the content, one is not missed. While this review is based on only a digital version of the book, the publisher is Rizzoli, renowned for its high quality in the fine printing market.

While “form follows function” in its most vigorous application could deliver fantastically efficient designs, it is the recognition of the human factor that puts a subjective check in the path of creating the most successful designs. An example on the far side of this idea was illustrated with the demolition of the old Penn Station in New York City and the erection of its uninspired but efficient replacement, inspiring architectural historian Vincent Scully to famously comment: “One entered the city like a god; one scuttles in now like a rat.” The architectural world has grown in the last fifty years. The reader of this book will know that beyond a purveyor of luxury apparel and accessories, Louis Vuitton has made a reasoned and stylish contribution to the world of architectural design.

Copyright 2012, Rubén Verdés (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter