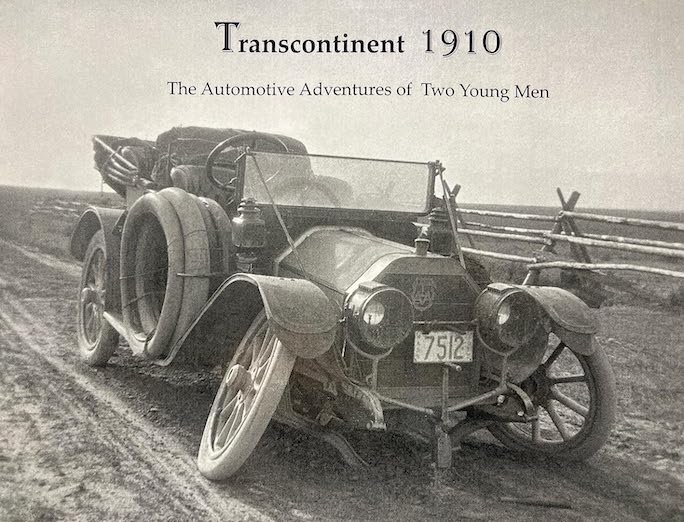

Transcontinent 1910: The Automotive Adventures of Two Young Men

by Mark H. Chaplin

“History is more or less bunk. It’s tradition. We don’t want tradition. We want to live in the present, and the only history that is worth a tinker’s damn is the history that we make today.”

—Henry Ford

In the years before and after 1910 (the year our story takes place) a whole lot of people beside Henry Ford were making history. Some were world famous. Peary had been to the North Pole and Shackleton was preparing to go to the South. The Wright brothers, having flown only 120 feet in 1903 had, by 1910, begun commercial flights between Dayton and Columbus. Freelan Stanley had driven his steamer to the top of Mt. Washington, the first automobilist to make the ascent. And Fred Marriott had opened up his Stanley Steamer on Ormond Beach to reach 127.66 mph—a speed record for steam-powered automobiles that stood till 2009.

Some history makers, however, were ordinary citizens, moved only by the urge to strike out on a new adventure that would take them where their fellow citizens had not gone before. Two of these adventurers were engineering students at what is now Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Among the obstacles history makers faced a hundred years ago was the vast north American continent itself—largely an unmapped open space, it was laced with rivers, mountain ranges, ditches, mud-holes, and thousands of miles of Indian trails and wagon tracks that only horse drawn vehicles could negotiate. Automobiles need not apply!

Conquering this trackless wasteland made fine publicity for ambitious automobile makers. Preparation was required, of course. Cars were specially designed and reinforced for the rigors of the journey. Parts were stashed at railroad depots along the route, as were caches of gasoline and oil. Even manufacturers whose cars failed to complete the entire trip got credit for trying. It is ironic then that the first automobile trip across the country in 1903 was made on a whim, by an amateur motorist with no sponsor, Horatio Nelson Jackson, to win a $50 dollar bet.

By 1910 when university students Alfred Hague and Joseph Fuller decided a coast-to-coast automobile trip would be the perfect way to spend their summer holiday, such trips were no longer unusual. Much had been learned about coast-to-coast driving and its hazards. But many drivers had failed and beginning the trip was no guarantee that car and driver would reach their destination. Hague and Fuller studied what was known about routes to be followed and equipment to be packed. Then, on June 25, 1910, they climbed aboard Fuller’s 1910 Oldsmobile touring car and set out from Boston for Portland, Oregon, 3086 miles away, intending to drive there and then back to Boston in time to register for the fall semester.

Automobiling was still front-page news in 1910 and embarking on a trip across America had some of the news value of setting out to swim the English Channel or trying to cross the Atlantic in a rowboat and the Hague/Fuller trip was sufficiently interesting to be covered by local and national reporters.

Press coverage was never lacking when the trip was factory sponsored. Hague and Fuller, however, were private citizens driving a car of their own. Still, in small towns along the route, many people had never seen an automobile, and reporters made sure that the public was not being starved for news when the big Oldsmobile appeared on the horizon.

Hague and Fuller’s trip made news in other ways. The drivers wandered off what had become traditional routes and, in the end, traveled an extra 1000 miles, losing their way, backtracking, and stopping to visit friends along the way. And, in addition to newspaper reports, they left behind a complete first-person, day-by-day log of the journey, written by Fuller himself. He not only kept a daily journal, he also sent a letter or postcard to his family every single day.

This self-published book reproduces Fuller’s correspondence and includes 120 illustrations—photos, maps, and copies of journal pages—in its 114 pages. The text of the book is entirely in Alfred Hughes’ words, without comment from editor Mark Chaplin. Crossing Montana, with Hughes as guide, the reader begins to feel as though he has opened a time capsule that’s been buried in the cornerstone of the local bank for 102 years.

Hughes was not an expansive storyteller. He was an engineer in training and inclined to report only the facts. His eloquence lies in the homely descriptions of the daily trials he and Fuller faced. The story was written on the road in spare moments, while it was happening. No one was sure what challenge the next day would bring, or whether they’d ever arrive at their destination. Listening carefully to Fuller’s voice, the frustration and the grinding daily routine begins to make you feel part of the trip. An axle breaks and you mutter to yourself, “we’re out in the middle of nowhere with only a few tools—how are we going to get this thing fixed?”

Transcontinent 1910 could as easily have been subtitled “technology vs. terrain.” The Oldsmobile is half the story, the ground it traveled is the other half. The car worked remarkably well. The engine flagged at times but never broke. That it was fully overhauled by these two college boys along the way is remarkable in itself. Brakes, transmission, and clutch met or exceeded expectations. The every-present enemy was the terrain. It rose up and snagged tie-rods. It broke springs again and again. Radius rod hangers (don’t ask) broke repeatedly. Irrigation ditches crossed the roads and barred progress. Streams often turned out to be impassable. Two or three hours to dig the car out of a mud-hole was routine.

Chaplin is a retired banker and a collector of vintage cars and antique clocks. He is also the author of Franklin Vintage: A History of the Car in Its Time (ISBN-13: 978-0979584107). Chaplin came upon this story at dinner one evening when his host, Fuller’s son, casually mentioned his father’s journal and scrapbook of photographs. Words and pictures together were sufficiently unique that Chaplin decided it was a story that deserved to be preserved and published. History buffs, enthusiasts of the West, and vintage car enthusiasts, will agree.

Copyright 2013, Arthur Einstein (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter