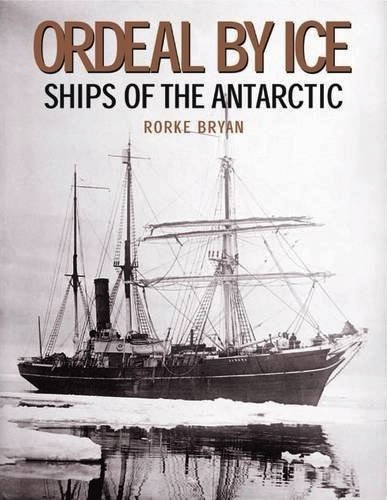

Ordeal by Ice: Ships of the Antarctic

“One would expect rational beings to avoid such a place at all costs, yet over the centuries, thousands of people have gone to extraordinary lengths to visit and to live there.”

Even with the planet relentlessly getting warmer, the mile/s-thick ice that covers 98% of Antarctica will keep it from becoming a summer resort any time soon.

The planet’s fifth-largest continent (twice the size of Australia which, along with South America, was shown on European maps as part of a vast hypothetical “Southern Land”—Terra Australis—until Captain James Cook in 1773/74 demonstrated otherwise) is its coldest, driest, windiest and actually considered a desert. Algae and mites—and penguins—like it fine but temps that can fall to −89 °C (−129 °F) make permanent human habitation unsustainable and even the few thousand temporary staff on research stations are glad not to be indefinitely marooned in this hostile environment.

The book’s title, then, is not just a catchy phrase. Author Bryan opens by saying that writing it has been a labor of love. That he didn’t write as just an armchair explorer is no small feat; in fact, he wrote some of it about 800 miles from the Pole, at research station Vostok, operational since 1957 and Russia’s farthest terrestrial outpost. The son of a merchant mariner he turned his lifelong interest in Antarctica into a profession if not a vocation. After studying Natural Sciences at Trinity College in his native Dublin he joined the British Antarctic Survey in the Falklands and now concerns himself with environmental conservation and forestry in his adopted Canada.

Published more or less concurrently by several publishers in several countries the book was launched at the annual 2011 Shackleton Autumn School, internationally known as “The Polar Event” and featuring a series of lecturers, exhibits, film, drama, an annual dinner, excursion, and re-enactment of that era. Ernest Shackleton became a principal figure in what we now call the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration and his 1916 escape from the ice after having to abandon his ship ranks as one of the most harrowing tales in the history of exploration, fully living up to the slogan on his recruiting posters: “Return uncertain.”

Given the human-interest angle of exploration and that people have eyed the South Pole for centuries it is remarkable that Bryan’s is the first attempt to compile a comprehensive account. Individual expeditions, ships, and explorers have been covered in detail before by others but Bryan weaves together many strands of the complex story of how advances in shipbuilding (the actual hardware), seamanship (navigation, cartography) and even ancillary developments such as food preservation, medicines, or communications relate to the exploration of an environment that even today remains largely uncharted. He writes: “The object of this book is not to disentangle the complex individual and societal motives which draw people to Antarctica, but to examine the pivotal role which ships have played in its exploration.” Even so, he devotes a great deal of attention to historical developments and geopolitical issues including whaling, territorial friction, and tourism.

Given the human-interest angle of exploration and that people have eyed the South Pole for centuries it is remarkable that Bryan’s is the first attempt to compile a comprehensive account. Individual expeditions, ships, and explorers have been covered in detail before by others but Bryan weaves together many strands of the complex story of how advances in shipbuilding (the actual hardware), seamanship (navigation, cartography) and even ancillary developments such as food preservation, medicines, or communications relate to the exploration of an environment that even today remains largely uncharted. He writes: “The object of this book is not to disentangle the complex individual and societal motives which draw people to Antarctica, but to examine the pivotal role which ships have played in its exploration.” Even so, he devotes a great deal of attention to historical developments and geopolitical issues including whaling, territorial friction, and tourism.

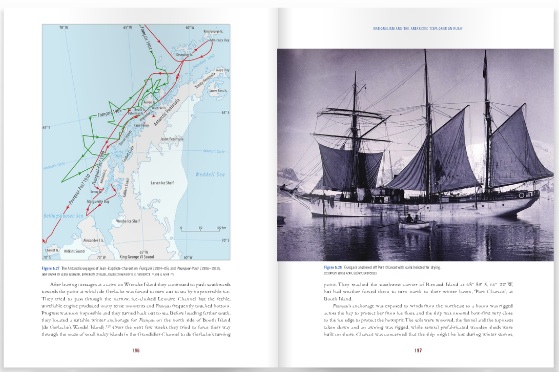

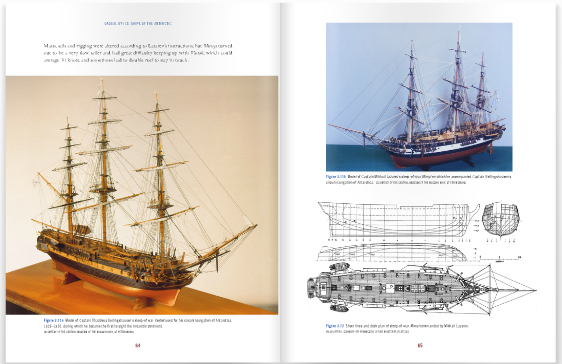

As to the ships, over 200 that “have made a significant contribution to Antarctic research and exploration” are discussed, right up to 2010. Bryan rightly begins his survey with the ancient Chinese whose 10th-century inventions and seafaring activities are only now recognized as predating European efforts by far. The ship-specific particulars—including technical and performance data and line art of cross sections and side views etc.—are embedded into the overall narrative. Maps naturally are a key part of this story and many have been rendered just for this book by cartographer Leena Baumann (University of Basel). The photo selection leaves nothing to be desired or to the imagination; all illustrations, which include several pieces of fine art and model ships, are suitably captioned and properly credited.

As to the ships, over 200 that “have made a significant contribution to Antarctic research and exploration” are discussed, right up to 2010. Bryan rightly begins his survey with the ancient Chinese whose 10th-century inventions and seafaring activities are only now recognized as predating European efforts by far. The ship-specific particulars—including technical and performance data and line art of cross sections and side views etc.—are embedded into the overall narrative. Maps naturally are a key part of this story and many have been rendered just for this book by cartographer Leena Baumann (University of Basel). The photo selection leaves nothing to be desired or to the imagination; all illustrations, which include several pieces of fine art and model ships, are suitably captioned and properly credited.

The first of three Appendices shows annotated sail plans of seven types of ships, another gives currency/purchasing power equivalents and 1804–2010 exchange rates, and the last one Ice Classifications of Vessels. Chapter Notes, good Glossary, deep Bibliography, very good Index with very useful subentries. For easy reference each of these sections is printed on different-color paper. The depth of this material is exemplary. If the book has a weakness it is a physical one: the flat spine is a poor choice for a 30 mm-tall book block.

Anyone with an imagination will find the almost incomprehensibly difficult early parts of this chapter of human endeavor moving. Whenever you feel you have a tough day, just pick up this book and read any random page! This book doesn’t really concern itself with why people started going and continue to go—commercial or military exploitation of this corner of the planet is basically prohibited—but it’ll tell you pretty much everything about the how.

Next time you watch the 1948 movie Scott of the Antarctic, the one that set young Master Bryan on his path, ask yourself if you might have missed your calling to whatever field. The musical score by Ralph Vaughan Williams is certainly rousing, even more so in its later recasting as his 7th symphony, the Sinfonia antartica (1952).

Copyright 2012, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter