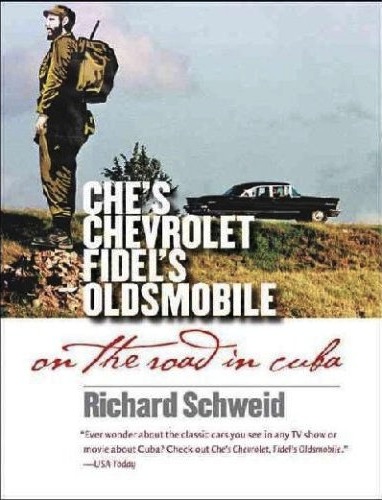

Che’s Chevrolet, Fidel’s Oldsmobile: On the Road in Cuba

by Richard Schweid

by Richard Schweid

A popular urban myth states that the island of Cuba is filled with pristine examples of American cars from the 1950s and, that when Fidel Castro finally dies, a wave of these befinned wonders will roll up on our shores. For his 2004 book Che’s Chevrolet, Fidel’s Oldsmobile: On the Road in Cuba, journalist and author Richard Schweid traveled throughout the island nation researching its automotive history. His story provides an interesting mix of early 20th Century motoring, the Cuban revolution in the 1950s, and how people in modern-day Cuba get from place to place.

The first car in Cuba arrived in 1898. It was a lightweight vehicle built by Parisienne that was purchased in Paris by a rich Havana resident. The second car, which was also purchased in France by a Cuban pharmacist, was a Rochet & Schneider that arrived in Havana in 1899.

Havana was the country’s capital, but it wasn’t the only place with automobiles. The first car in Santiago de Cuba arrived in May 1902. It was a steam-powered Locomobile, built by Locomobile & Company in New York. Soon, gasoline, steam and electric powered cars could be seen in several of Cuba’s other cities and larger towns. They were of limited use however as although the streets within Cuba’s cities were drivable, the roads between towns in the countryside were all but impassable. In 1908, an American journalist named Ralph Estep drove a Packard automobile from Havana to the inland town Sancti Spíritus, taking nine days to cover the 313 miles.

By the late 1920s and 30s, road building began to link the towns and automobile importing increased. American cars, particularly inexpensive and rugged models built by Ford and Chevrolet, became popular among the middle class. Upper range models from Buick, Lincoln, Cadillac, and Packard provided mobility to American gangsters who opened gambling casinos and ran liquor from the island during America’s prohibition period.

Schweid’s book covers these eras well, but it is the revolutionary 1950s that really catches his attention. From 1950 to 1958 the number of cars on the island more than doubled, from 70,000 to 167,000. The vast majority of these automobiles were American built, although importation of the Ford Prefect and a few Jaguars also occurred.

Under Batista’s rule, Cuba was sharply divided between the rich and the extremely poor making it ripe for revolution. Batista was friendly with the American car companies and saw automobiles as a way to show the world that Cuba was prospering. The inaugural Grand Prix of Cuba, held in 1957, was won by Juan Manuel Fangio. The night before the second Cuban Grand Prix race in February 1958, Formula One champion Fangio was kidnapped by rebels as a political statement. Noting that Fangio had been whisked away in a green 1957 Plymouth and returned, after the race to the Argentine ambassador, in a gray 1957 Rambler, led Schweid to carefully reconstruct the various automotive choices of Fidel Castro and other Cuban revolutionaries. Thus we learn that Castro traveled to Santiago for his 1953 attack on government forces at Moncada in a rented blue 1952 Buick; that he rode into Havana in 1959 in a Willys Jeep; and after the revolution Che Guevara’s preference was for a green 1960 Chevrolet Bel Air.

Following the revolution and with the subsequent embargo by the United States, no new American cars came into Cuba from that source so replacement parts grew scarce. Rather than scrap their cars, Cubans became adept at adapting parts from other machines in order to keep them on the road. They call these cars cacharros (literally the masculine noun meaning coarse earthen pot or pots and pans. Used colloquially, it has become synonymous with word “junk” or “jalopy.” ) A 1957 Chevrolet taxi may be running with a Russian diesel truck engine transplanted under its hood, or with a carburetor from an Eastern bloc country automobile grafted onto its cylinder heads. Cuban mechanics are geniuses at improvisation and Schweid spent enough time living in the country to meet several mechanics and car owners, ride the local two-cent bus, do his research in Havana’s José Marti National Library, visit with car clubs and automobile museums, participate in an old car parade and rally and learn of the love Cubans have for their automobiles.

Unfortunately, although clearly besotted with the appearance of big-finned American cars of the 50s, the author’s automotive knowledge occasionally lags behind his enthusiasm. A careful reader will find his errors jarring. Read for its insights into Cuban society and the events before and after the revolution, the book is informative as the author clearly did a great deal of research. However information echoes or repeats from one chapter to the next, with the narrative rambling at times.

But what of the urban myth about those “pristine” 50s cars awaiting liberation back to the States? Schweid is optimistic that some cars are still original enough to warrant interest from serious collectors, but he also notes, “A pampered old age is not what awaits the vast majority of North American cars in Cuba, the cacharros with their battered bodies and smoking modified engines, their Lada carburetors and Fiat Polski points, or tubing coiled around the tailpipe to heat kerosene as it passes through on its way to a mongrel engine. Who will want them?” On the other hand, Schweid hints that some rich Cubans, living in Miami, have already purchased some of the best original cars and have them hidden away in the Cuban countryside, waiting for Fidel to die so that the cars can be sold on the worldwide market. Another urban legend?

Copyright 2009 Kevin Clemens (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter