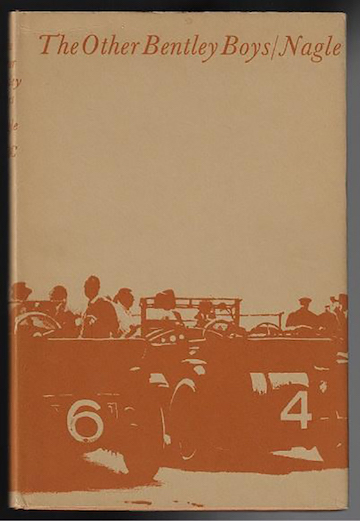

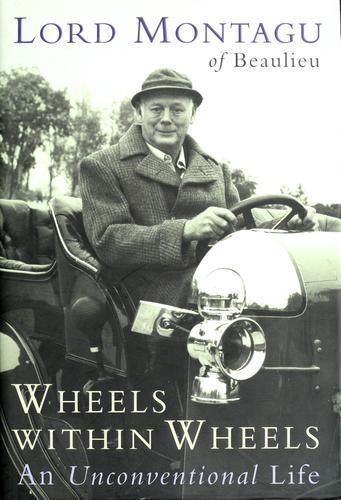

For the Love of Old Cars: The Jack Passey Story

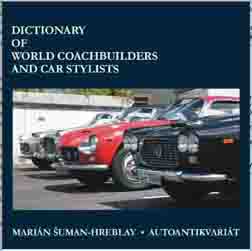

“Some of them, in my opinion, have been destroyed, because people have taken cars that have been beautifully preserved and they should have kept them that way for their historic value. But they have restored them so they could get a $20 or $50 trophy. It’s an ego thing. You should take a fabulous car that has been preserved and keep it that way because it can only be original once. . . . True there are some fabulous restorations, which I am totally in favor of if the car needed it. But if you take a car and do it just because you want to win a prize, then you don’t love that car . . . you just want the prize and the car is the tool to get it.”

Now in his eighties, Jack Passey has had a thing for cars since he cannibalized his uncle’s magazines for car photos as a young boy. And in his case, that thing really is love. In the early days he would not have the heart to drive by an old car (which then would be from the 1910s or ‘20s) with a For Sale sign on it and leave it to an uncertain fate. He would turn over his pants pockets and sofa pillows to round up a fistful of dollars, or work out a monthly payment plan or work an extra job just to “save” a car from the crusher. Later on, he would not have the heart to sell a car to just anybody if that person “didn’t talk right about the car,” meaning with respect and admiration and a believable commitment to preserving or restoring it.

While anyone with a sensibility about cars will relate to the Passey story, few even of his contemporaries can say they saw the light the way he did, and certainly not on his order. Anyone who was of car-buying age since before WWII will recall the days when big old prewar cars were so passé that they only had scrap value. In the 1950s when Passey charged $4 an hour for his auto repair work he could buy an old Duesie for $150. Anybody could have done it—but few did, and fewer still did it for Passey’s reasons, and that’s what sets his story apart.

Among enthusiasts of vintage cars, especially American ones, Passey’s name for decades had and has currency as a restorer, purveyor of parts, car broker, collector, and concours judge. The symbiotic connection among these various strands make his life story unusual, and his early championing of the preservationist cause makes him seem prescient now. It wasn’t until 2002 that the Pebble Beach concours, where Passey has judged for almost 40 years, launched a Preservation Class—the first one fittingly won by a 1919 Locomobile of his. And five years after this book was written, Pebble Beach presented him with the 2013 Lorin Tryon Trophy that recognizes “an automotive enthusiast who has contributed significantly to the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance.”

Who could have known that a person shown on the opening pages of this book in a family photo as a tiny toddler would be the one to drive Passey over the winner’s ramp that day, after earlier taking one of his Lincolns onto the show field and presenting it to the judges? This was his 16-year-old granddaughter, and to see now a third generation of Passeys share a love of old cars, and to see old cars being cherished would have validated everything young Jack once dreamt of in his optimistic but impecunious days.

If only by accident, the life he chose has also made him wealthy but, more importantly, it is a life he considers well lived. And that’s why we have this book, not as a 12-Step program to making a name in the car world but as a look at, on the one hand, being in the right place at the right time while, on the other hand, having eyes to see what others don’t.

The book lists as author Ken Albert who offers a one-page introduction explaining how he came to “write” the book he calls an “Auto-Biography” as it is, obviously, about autos. However, the book is literally an autobiography because throughout Passey speaks in the first person, with no evidence of authorial/editorial intervention, be it in the form of polishing prose and grammar or providing context for, say, names and places, or offering any sort of independent commentary. This hands-off approach preserves Passey’s voice but makes for tedious reading—there’s relentless “I said / He said / I said / He said”—and seems an uninspired choice on the part of someone who not only is a writer of several books (recreational and trade titles) but ran his own publishing company (which makes the typos all the more inexcusable).

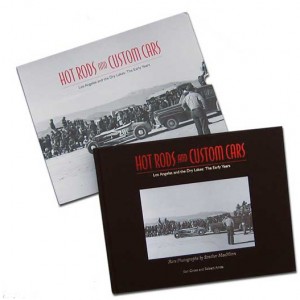

The extraordinarily detailed Table of Contents almost serves as an Index (which is quite serviceable on its own) and points the way to people and cars. The book’s landscape format is an ideal canvas for car photos, all of which are b/w, even the modern-day ones. The captions are rather perfunctory and superficial, rarely drawing the reader’s eye to Passey’s very specific taste, interests, and reasons for favoring one make or model over another.

Passey always had a reputation for having a photographic memory and encyclopedic knowledge and it is a splendid thing that he allowed Albert and others to nudge him into letting someone record it. If you are into vintage and classic American cars and especially if you know some of the players on that stage (collectors, auctions, museums) his book will connect many dots.

Copyright 2013, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter