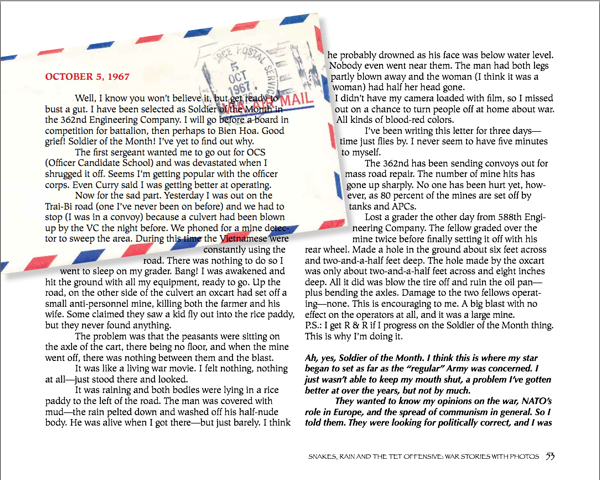

Snakes, Rain and the Tet Offensive: War Stories with Photos

Memoirs from wars, past or present, tend to cover the spectrum of literary form and expression: some are graceful and highly articulate, others just the opposite, awkward and often incoherent. Most are somewhere in between. Relatively few soldiers sit down and put their words on paper and then keep them. Fewer soldiers still illustrate their memoirs with photographs of the quality that one finds in this book.

There were, as the cliché goes, many, many Vietnam Wars. Time and place dictate just which war one might be experiencing and this is, of course, true of wars in general. Of the vast numbers serving in the U.S. First Army only a relative few endured Omaha Beach on the morning of D-Day. Similarly, not everyone in either the Army of the Potomac or the Army of Northern Virginia was present on the afternoon of 3 July 1863, when what may have been the high tide of the Confederacy finally ebbed.

One of the other realities of modern war is that only a relative few actually do much of the fighting. Most everybody else is occupied in some sort of support role. In Vietnam, perhaps only 10 to 20% of those present were there as actual combatants, with the latter number being either rather optimistic or simply vague—and definitely on the high side. Thus, contrary to the commonly accepted image often found in the movies or on television or in far too many books, the vast majority of soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines sent to Vietnam spent most of their time in the rear echelon areas, such as they were.

Alongside the combat arms—the infantry, armor, field artillery, and the combat engineers and those in combat aviation—were those deployed in combat support and combat service support roles. The latter groups were the men (and a few women) who built and maintained the bases, unloaded and loaded supplies, prepared meals, manned communications sites, drove and maintained the trucks on the resupply convoys, kept the paperwork flowing, and handled the many other tasks necessary to keep the modern military functioning. For the most part, their problem was not the Viet Cong or the North Vietnamese Regulars, but boredom and being far from home.

Bill Ingalls witnessed his Vietnam War as a 62 Echo, the code used to designate the Military Occupational Specialty (MOS) for Heavy Construction Equipment Operator. From August 1967 to July 1968, Ingalls fought his war from the seat of a road grader as a member of the 362d Engineer (Light Equipment) Company. His general area of operations was in the Tay Ninh area, which is to the northwest of Saigon.

The body of the book is primarily drawn from letters he sent home to his wife, obviously with no intent of ever publishing or possibly even seeing them again. They faithfully capture both the ennui and the relatively few moments of excitement (or terror) of being at war. Military historians have long known that the diaries and letters of soldiers are an excellent source for weather data and Ingalls does include this vital element in his letters.

The narrative that now connects the letters was added after Ingalls during a bout of office cleaning half a century later came across his old photos. Seeing them stirred up memories—and the thought that others might find it useful to see an aspect of the war not really recorded in any detail elsewhere.

The 275 full-color photos are what set this memoir apart from the many other, similar recollections of Vietnam. That Ingalls had the opportunity to take them in the first place is as remarkable as having held on to them for all these years (and in good enough shape to allow such superb reproduction here). The photographs of what Ingalls refers to as the “Cambodian Border Adventure” tend to be the sort that one rarely sees of the war: what it is like to be a combat support troop caught in a combat operation. “Not fun,” would probably not begin to describe the experience.

The 275 full-color photos are what set this memoir apart from the many other, similar recollections of Vietnam. That Ingalls had the opportunity to take them in the first place is as remarkable as having held on to them for all these years (and in good enough shape to allow such superb reproduction here). The photographs of what Ingalls refers to as the “Cambodian Border Adventure” tend to be the sort that one rarely sees of the war: what it is like to be a combat support troop caught in a combat operation. “Not fun,” would probably not begin to describe the experience.

I found that simply looking at the photos was often enough to gain a feeling for the war that Bill Ingalls experienced. In all honesty, his war was so radically different from my war (again, time and place, as well as luck of the draw—life as a 62E seems to have been quite a lot better in most ways than mine as an 11B, Infantryman) that I found myself quite fascinated by it, and the photos are a major part of that fascination. It does not hurt that Ingalls is quite blunt and leaves very little out in this book; this is not always a “good thing” in some cases, but works quite well in this instance.

Over the years, I have probably read far more memoirs written by soldiers regarding their wartime experiences than I can even begin to number, with more than a few being from the Vietnam War. Inevitably, a sense of “memoir fatigue” sets in—leavened with a good dose of cynicism, when the BS Indicator is tripped in far too many cases. This book is not your run-of-the-mill Vietnam War memoir by a long shot—and the beautiful illustrations set it far apart from the others.

The book’s first printing is limited to 150 numbered and signed copies.

Copyright 2015, Don Capps (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

I have been privileged to see this terrific book and read Bill’s colorful accounts of his experiences. What a great personal story told with panache. The photos are unforgettable!

Great book! Great interviews!