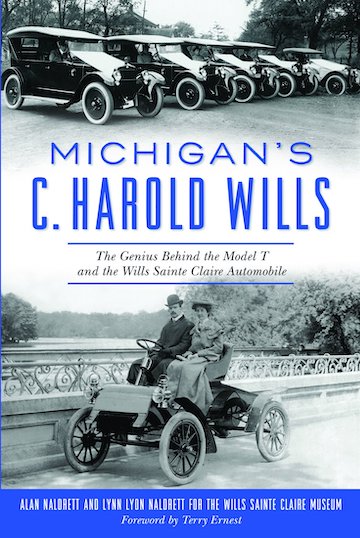

Michigan’s C. Harold Wills

The Genius Behind the Model T and the Wills Sainte Claire Automobile

by Alan Naldrett and Lynn Lyon Naldrett

by Alan Naldrett and Lynn Lyon Naldrett

When the review copy arrived I was heartened by the credentials of its authors; a husband/wife team with he, Alan Naldrett, now a retired research librarian and she, Lynn Lyon Naldrett, with a master’s degree who assists with historical presentations. Their words in the Afterword titled “Or, when legend becomes fact” where they wrote “One wants to find two sources to be sure of a fact,” and thanking in their Acknowledgements a coterie of proofreaders, fact checkers, and others who’d helped them source information seemed to imply their words in the text would be of good quality.

Yet, as the typos accumulated as I read, it became more than likely they weren’t mere typos. So I started questioning and verifying their assertions.

One early sentence “clanked” immediately. “The system was one he [referring to J. Walter Christie] developed while driving…tanks during the Spanish-American War.” Memory told me that conflict had taken place somewhere in the 1890s, so how could there have been motorized tanks already in existence when the horseless carriage was only on the cusp of its debut? A bit of research supported my initial reaction. When the Spanish-American War was contested, the reality of a tank was still two decades in the future and initial ones would come from British minds and military needs.

When, on a later page, the Naldretts had written, “Wills had a molybdenite mine he had purchased in Climax, Colorado in 1918” the timeline just seemed unlikely as Wills was still in the employ of Henry Ford at the time and Ford had declined to use moly-strengthened steel preferring to use his own Rouge-produced vanadium steel. So I keyed Climax, Colorado into the search engine and discovered another book titled simply Climax written by Stephen M. Voynick, first published in 1996 with a second printing a year later. I was able to obtain a copy through the local library’s inter-library loan program. It was an excellent read and what the book about Wills coulda/shoulda been—well researched and documented down to the last crossed tee and dotted i, with nary a typo to be found on any of its 376 pages.

Voynick’s words about Wills indicate it wasn’t in 1918, but rather a year later after Wills had resigned from Ford’s employ, where and for whom he had indeed made large engineering contributions to every Ford-developed car, including the T, since Ford’s earliest days of the 1900s. And Wills had not purchased the mine! It wasn’t for sale, only its “product” was.

Following his resignation Wills determined he would build and market his own automobile, the Wills Sainte Claire, and very much wanted to use molybdenum-alloyed steel. By happenstance he met Climax Mine president Brainerd Phillipson who was seeking customers for his mine’s product which “had a deposit of ore so large that he was able to guarantee unlimited supplies at the lowest possible price.”

Two sentences in Voynick’s book explain succinctly that: “Molybdenum, a silver-gray metal derived from molybdenite, is about as heavy as lead but less commonly occurring in nature, was assigned the atomic number of 42. [Its] two most notable properties are a melting point of 4,730 degrees Fahrenheit, about 2,000 degrees higher than most steels, and an…ability to toughen steel” not by hardening it directly but rather “repressing brittleness, thus permitting more extreme tempering to produce greater hardness.”

He goes on to describe Wills’ first Wills Sainte Claire, that debuted spring of 1921, dubbed “The Gray Goose,” as a “superb balance of beauty, style, performance, and advanced engineering” with “every component of the engine, power train, frame and suspension system subject to even minimal stress consisting of molybdenum steel.” The Naldretts write similarly but with many more words yet expressing fewer specifics or details. Both acknowledge, as did Maurice Hendry in his article on Wills, the man and his car, in Automobile Quarterly Volume 5, Number 2, that the car came to be known as “The Molybdenum Car.”

By far Hendry’s article published in fall of 1966 is the most complete and detailed—and comprehensively readable. The Naldretts jumble the timeline, dropping details. As an instance, Wills’ major contribution to the World War I Liberty bombers is one small sentence in Naldrett’s book inserted in chapter 9 titled “The C.H. Wills Company” which wasn’t even formed until 1920 yet his significant engineering work on the Liberty 8 engines, as detailed by Hendry, had taken place already in 1917 while still working with Henry Ford at Ford’s Highland Park plant.

Although the book has additional factual errors in addition to all the “typos” it is not without worth or value to the automotive historian for it is generously illustrated with the photos made possible by the Naldretts working with the Wills Auto Museum. Over time the museum has built its archives of information and photos thus many/most in the book have not appeared previously in print. Publisher The History Press is an arm of Arcadia Publishing thus the physical book is well-produced, with sharp, clear photo reproduction, and it has both Bibliography and Index. (Still more images are on the museum’s website: WillsAutoMuseum.org)

Copyright 2019, Helen V Hutchings (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter