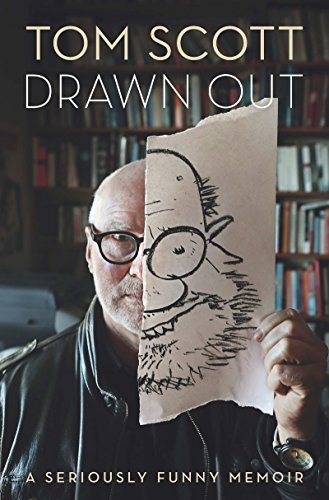

Drawn Out, A Seriously Funny Memoir

Arranged inconveniently over a very active fault line, with matching active volcanoes, adrift in a stormy bit of the South Pacific Ocean, New Zealand measures 103,000 square miles, many of them vertical, and is inhabited by almost 5 million people, about the size of a middling city elsewhere. Just how this small nation, as far away as it is possible to travel from the British who colonized it 200 years ago, and 500 years after its original Polynesian Maori settled, has produced a line of world-renowned nuclear physicists, space scientists, mountaineers, film makers, and sports stars, may be a mystery, but this book will go a long way to explaining it.

Tom Scott was born a twin in London in 1947, from a fleeting alliance of a Northern Irish Protestant father and a Catholic mother from the south. Joan Ronayne’s brothers later tracked down Tom Scott Senior, and delivered him, slightly battered, to the Registry Office, and the family came to New Zealand soon after, settling in the small North Island town of Feilding. Author Scott’s difficult relationship with his father culminated in the play “The Daylight Atheist” (2002), and the “…brilliant man, a comic genius at times, denied by fate and circumstances the chance to express his creativity, which left him deeply frustrated” managed to pass on some of those qualities and caveats to his son. A member of the next generation, Samuel Flynn Scott is a Wellington musician.

An awkwardly shaped and short-sighted boy, Scott compensated for his difficulties by honing his drawing and writing skills. There was a wealth of comic material available in that era when Peter Sellers, Spike Milligan, Peter Cook, Dudley Moore, Tom Lehrer, Joseph Heller, Gerald Scarfe, Stan Freberg, David Levine, Ronald Searle, Ralph Steadman, Mad Magazine, Hunter S. Thompson, Mort Drucker, Herb Block, and Clive James influenced us all. School at Feilding Agricultural College was followed by Massey University in nearby Palmerston North, and after editing the weekly “Masskerade”and failing at veterinary training, there was a variety of mundane jobs before a tutoring post at a technical college near Wellington came his way. Here he “…walked from the CIT campus to the windswept Petone foreshore, where seagulls huddled together for warmth, and stared longingly at the glittering capital city across the water. I felt like Nelson Mandela staring across at Cape Town from the prison rock of Robben Island. Apart from him being locked up at night in a small, damp concrete cell, sleeping on a straw mattress. Apart from him breaking rocks in a lime quarry by day without sunglasses and suffering permanent eye damage as a result. Apart from being allowed only a handful of visitors and denied access to newspapers. Apart from being denied permission to attend the funeral of his mother or his first-born son. Apart from being subjected to verbal and physical abuse from some Afrikaner guards—apart from all that—our experiences were identical.”

In that passage there is the first hint of the important contribution Scott made in managing to unravel the official support of the New Zealand Government, under its repressive Prime Minister Robert Muldoon (1921–92), for the apartheid regime in South Africa. More of that later…

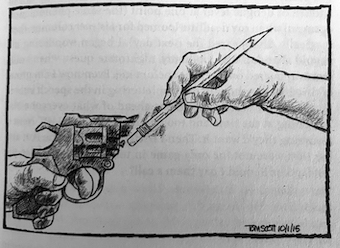

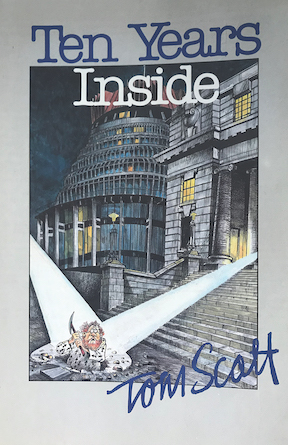

The fairly liberal Evening Post, still family-owned in those pre-Murdoch days, hired Scott as its cartoonist, and from then his work appeared in other New Zealand newspapers, but his break came when he joined The Listener, to write and illustrate a weekly column in 1974. His collected work, prescient, often savage but usually funny even now, in such books as Ten Years Inside, (1985), Snakes and Leaders, (1981), Overseizure (1978) and In a Jugular Vein (1991) still brings vivid memories to those of us who were around at the time, and likely to encounter Scott browsing the same bookshops.

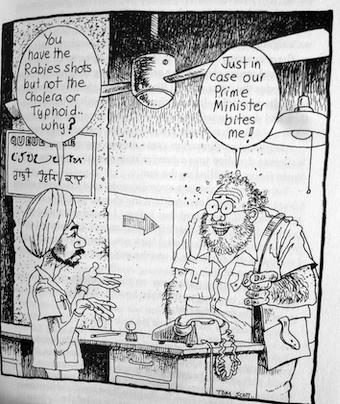

The Listener then as now brought its loyal readership a fine leavening of criticism literary, visual arts and political, to the expected “lifestyle” components, and Scott’s eagerly awaited commentary from Parliament had already brought him to Muldoon’s attention by 1974. At a Press Gallery function, after the Leader of the Opposition, Jack Marshall (1912–88), had greeted Scott with his usual courtesy, Muldoon the Deputy Leader, about to depose Marshall, refused to shake Scott’s hand. “Gentleman Jack” had earlier been admired by the British Press as he gracefully accepted, as New Zealand’s Prime Minister, the terms, or lack of them, accorded to a British Commonwealth country as Britain hastened to join the European Common Market, and always had a wave to walkers outside his farm. We were never engulfed in his dust, as the tar seal extended as far as his gate…

During the next ten years, Scott’s period of “fear and loathing” lasted until Muldoon’s government fell to a landslide victory to Labour, in which Prime Minister David Lange (1942–2005) seemed unable to moderate the neo-liberal agenda which used New Zealand as a conveniently sized test tube for the policies which have done so much to bring us the world which now faces us all. So small is New Zealand that this reviewer had his own “fear and loathing” moment when he realized that the pale blue Triumph 2500 sitting in the other lane at the traffic lights had the Right Honourable Robert Muldoon at the helm. Here was a Prime Minister who kept such a tight rein on his country, that he went on national television to announce the increase of the toll on the Auckland Harbour Bridge from 20 to 25 cents. This was just before a bye-election, and so enraged voters in the affected electorate that they didn’t vote in the candidate, perceived as a threat, of his own party. While there were black comedic aspects of the power Muldoon and his information about who knows what about whom, gleaned from his relationship with the Security Intelligence Service, wielded over the country, it was not a happy time. Apartheid South Africa was supported, in the face of disapproval from most of the world, by New Zealand at successive Commonwealth Heads of Government Meetings, and culminated in the bitterly opposed rugby Springbok tour to New Zealand in 1981, when the worst elements of police riot control suppressed opposition. Even after Lange’s government had been succeeded by a return to government by the National Party, its Prime Minister, Jim Bolger (b1935), couldn’t possibly officially appeal for the release of Nelson Mandela before his 70th birthday, as “he’s a terrorist”. In as neat a piece of hypocrisy as one could wish to see, Lange, who had fought long and hard against racist policies, had to pay his own fare in 1991, rather than join Bolger’s junket to Mandela’s inauguration as President of South Africa. There was an interesting sequel to this, when the Press Gallery learned of Mandela’s 1995 visit to New Zealand in time to gazump the official programme, and Bolger’s offer to introduce the honoured guest at the 125th anniversary of the Press Gallery was declined.

During the next ten years, Scott’s period of “fear and loathing” lasted until Muldoon’s government fell to a landslide victory to Labour, in which Prime Minister David Lange (1942–2005) seemed unable to moderate the neo-liberal agenda which used New Zealand as a conveniently sized test tube for the policies which have done so much to bring us the world which now faces us all. So small is New Zealand that this reviewer had his own “fear and loathing” moment when he realized that the pale blue Triumph 2500 sitting in the other lane at the traffic lights had the Right Honourable Robert Muldoon at the helm. Here was a Prime Minister who kept such a tight rein on his country, that he went on national television to announce the increase of the toll on the Auckland Harbour Bridge from 20 to 25 cents. This was just before a bye-election, and so enraged voters in the affected electorate that they didn’t vote in the candidate, perceived as a threat, of his own party. While there were black comedic aspects of the power Muldoon and his information about who knows what about whom, gleaned from his relationship with the Security Intelligence Service, wielded over the country, it was not a happy time. Apartheid South Africa was supported, in the face of disapproval from most of the world, by New Zealand at successive Commonwealth Heads of Government Meetings, and culminated in the bitterly opposed rugby Springbok tour to New Zealand in 1981, when the worst elements of police riot control suppressed opposition. Even after Lange’s government had been succeeded by a return to government by the National Party, its Prime Minister, Jim Bolger (b1935), couldn’t possibly officially appeal for the release of Nelson Mandela before his 70th birthday, as “he’s a terrorist”. In as neat a piece of hypocrisy as one could wish to see, Lange, who had fought long and hard against racist policies, had to pay his own fare in 1991, rather than join Bolger’s junket to Mandela’s inauguration as President of South Africa. There was an interesting sequel to this, when the Press Gallery learned of Mandela’s 1995 visit to New Zealand in time to gazump the official programme, and Bolger’s offer to introduce the honoured guest at the 125th anniversary of the Press Gallery was declined.

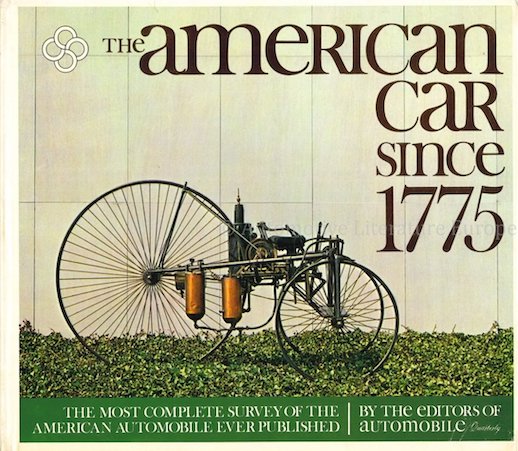

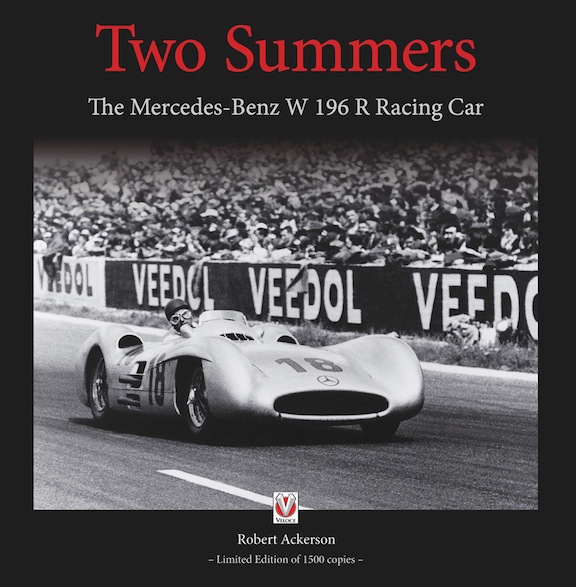

It’s all here, on the page and between the lines. There is not much Speed in here, apart from a BSA 650 motorbike, the cars mentioned being usually those dreadful examples of British design as Morris 8 Sports, Bedford Dormobile and Ford Cortina.

It’s all here, on the page and between the lines. There is not much Speed in here, apart from a BSA 650 motorbike, the cars mentioned being usually those dreadful examples of British design as Morris 8 Sports, Bedford Dormobile and Ford Cortina.

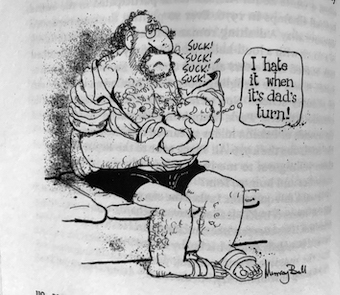

I hope this book whets your appetite for the work of other New Zealand satirists, from David Low (1891–1963), who was on Hitler’s “Hit List;” through Murray Ball (1939–2017) creator of Stanley the Great Palaeolithic Hero published in Punch, a mentor of Scott and born in the same small town; Alan Grant (1941–2000), as funny in high school as your reviewer remembers, as in all his writing; and John Clarke (1948–2017). If there’s a theme here, it’s that everybody has passed on. Luckily, that is not the case with Scott, or the talented generation who have followed him, such as Jemaine Clement and Taika Waititi (or Cohen if he uses his mother’s name). Enjoy!

Copyright 2020, Tom King (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter