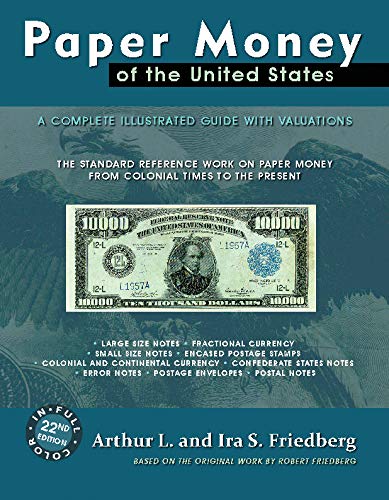

Paper Money of the United States

by Arthur L. and Ira S. Friedberg

by Arthur L. and Ira S. Friedberg

The love of money just might be the root of evil, but to United States paper currency collectors, the love of money is not necessarily avarice. For the collectors of baseball cards, stamps, LPs, Beanie Babies, Hot Wheels, Ferraris—well, you name it—condition and rarity play a large part in an object’s desirability and worth. And this is so for the collectors of United States paper money, but there is more to consider. The historic resonance of these notes is strong as is the aesthetics of their design and fine engraving.

Quick quiz: Who is portrayed on the $1, $20, $100 and $100,000 bill? If you guessed Woodrow Wilson for the last of these, you probably already own this book. If you guessed George Washington, Andrew Jackson, Benjamin Franklin, respectively, for the first three, you would be correct—but not entirely correct: The 1886 $1 Silver Certificate has an engraving of Martha Washington; the 1902 $20 Federal Reserve Note shows Grover Cleveland; and James Monroe is depicted on the 1878 $100 Silver Certificate. And, yes, in 1934, the government printed $100,000 Gold Certificates; these were not for general circulation, but used for bank transactions only.

Paper Money is a scholarly production. The book explains and explores the various types of paper money issued, over the centuries, by the United States: Demand Notes, Legal Tender Notes, National Bank Notes, Silver Certificates, Gold Certificates, et al. (Today, Federal Reserve Notes are being issued and circulated, pieces of paper backed not by silver or gold but by the faith and trust we hold in the United States Government.) Fractional currency and Confederate bills are also found in the book. Imagine a 50¢ paper note with a portrait of Abraham Lincoln. Why fractional currency was printed is explained, and some images found on the Confederate bills are uncomfortably fascinating. The cataloguing for all examples of paper money is quite detailed, and the current value of each, based, as mentioned, on scarcity and condition, is given. The layout and design of Paper Money is attractive. All illustrations are in color—and, by law, shown smaller than the actual bills; these illustrations are sharp and clear. The engraving found on many of the bills, especially those of the late 19th and the early 20th century, are beautiful works of the engraver’s art.

An extensive, quality collection will not come cheap: An 1880 series Rosecrans/Nebeker $1 National Bank Note, with a large brown seal—$12,500; the 1875 $50 National Bank Notes, showing Washington crossing the Delaware on the obverse and the embarkation of the Pilgrims on the reverse, are valued, on the high end, at $45,000; a 1918 series $1000 Federal Reserve Note, with White/Mellon signatures, is listed at $130,000; an 1880 series $1000 Legal Tender Note, with Vernon/Treat signatures, in excellent condition, could set you back $216,000. Some notes have changed hands for millions. But if the market for these notes were to somehow freakishly bottom out, if the collectability of them would somehow become irrelevant, United States paper notes, whether printed yesterday or two hundred years ago, are still legal tender and will never lose the note’s face value. Even for those who lack the collector gene, Paper Money would be a sound investment. The interest in and the allure of money run deep.

A final note (pun intended): Fans of Speedreaders, car people, especially those of a certain age, may recall that on the reverse of the $10 bill, series 1933 to series 1995, three automobiles are shown. The two in the background are tiny; the third, in the foreground, drives past the Treasury Building. Some swear it is a Ford Model T, others say a Ford Model A. Still others claim it’s a Hupmobile. The general consensus is that these cars are generic.

A final note (pun intended): Fans of Speedreaders, car people, especially those of a certain age, may recall that on the reverse of the $10 bill, series 1933 to series 1995, three automobiles are shown. The two in the background are tiny; the third, in the foreground, drives past the Treasury Building. Some swear it is a Ford Model T, others say a Ford Model A. Still others claim it’s a Hupmobile. The general consensus is that these cars are generic.

Copyright 2022 Bill Wolf (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter