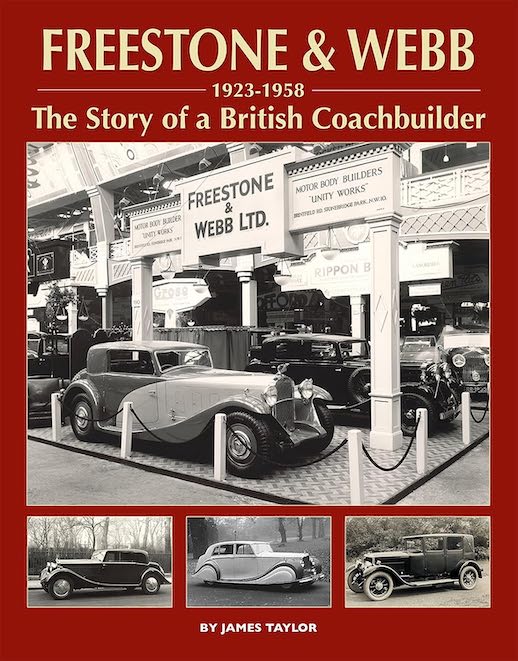

Freestone & Webb, 1923–1958

The Story of a British Coachbuilder

by James Taylor

by James Taylor

In 2006 the publishers Herridge & Sons released Coachwork on Vintage Bentleys, the first of what has proven to be a consistently admirable, uniform series on primarily but by no means exclusively British coachwork.

Initially concentrating on the years between the world wars—almost universally recognized as the Golden Age of coachbuilding—the series has been expanded to cover the post-WWII twilight years of the traditional coachbuilding era. Its successful formula involves a standardized physical format of A4 dimensions, which gives the volumes adequate size and heft, as well as adequate room for the use of photos, in the sense of Rolls-Royce listing their cars’ horsepower as “adequate.” Perhaps just barely adequate? More on that in a bit.

Because of this common format, the books present a most attractive appearance when grouped together on the bookshelf. The internal format too is highly similar, if not quite identical volume to volume, but it provides a consistency that makes the series an easy-to-use reference tool. Once you learn the format, which isn’t at all difficult, finding specific information of a similar nature in the companion volumes is a simple task. All the volumes make good use of historic black and white photography as well as modern color photos of which a good number are taken specifically for the book/s. Overall, photographic reproduction is at least very good to excellent, with thankfully rare inevitable exceptions, of course. Those exceptions invariably fall in the “A poor historic photo is better than none” category, though a very small number are of such poor quality they arguably may cast some doubt on that. In those few cases it might be better to assert that “A vague idea is better than no physical evidence whatsoever.”

That first volume was written by the late Nick Walker, with modern photography by Rowan Isaac. An unusual feature with all of these volumes is the photographer’s name prominently displayed along with that of the author. This seems only fair, as a substantial portion of each volume is composed of the aforementioned superb modern color photography that in most cases tells the story and fills in the blanks better than the often muted b/w historic photos. Blame the lack of contrast in many of those photos on the typically cloudy environment of the British Isles on the day the photo was taken, and not on hasty darkroom work. Another comment on the historic b/w photos that is more or less consistent volume to volume is the disappointingly small size of a great many of them, which makes appreciating subtle details extremely difficult, if not nearly impossible. This new volume is no exception in this regard and is due to the inevitable editorial conflict between size of the book, size and quantity of photos, and retail price. These books are not inexpensive to produce. Consequently, their pricing reflects the necessary compromises involved in producing a book that will be sufficiently attractive to a sufficiently wide audience that it can be expected to sell in adequate numbers. That the series continues to grow is a good indication that the publishers have hit the sweet spot.

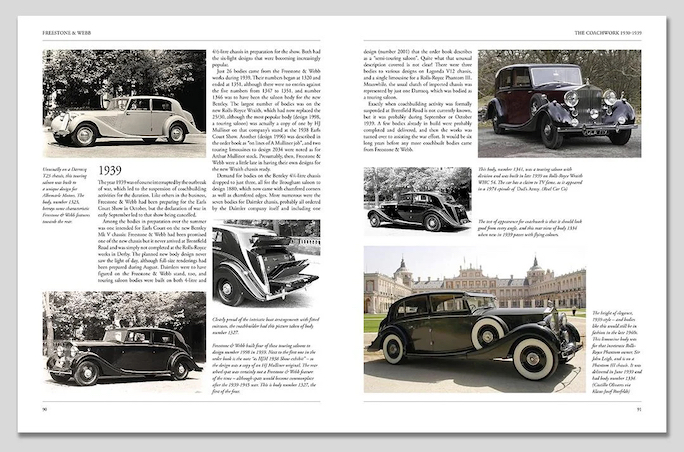

James Taylor, a recognized authority on the subjects of high-grade chassis manufacturers and coachwork in general, has repeatedly proven himself to be more than equal to the task of properly and accurately researching each of the specific topics on which he has chosen to concentrate, thereby assuring the enduring reference value of his endeavors. Regarding British coachwork, he has authored Coachwork on Derby Bentleys (2018), Coachwork on Rolls-Royce and Bentley 1945–1965 (2019), Coachwork on Rolls-Royce Twenty, 20/25, 25/30 & Wraith 1922–1939 (2021), and now Freestone & Webb 1923–1958, The Story of a British Coachbuilder (2021).

Freestone & Webb, the smallest and weakest of the “Big Five” coachbuilders to resume traditional coachbuilding after WWII, were nonetheless well-known and internationally respected purveyors of their craft. The company’s story has never been told in any degree of detail, possibly due to the incomplete preservation of the company’s records following the closing of its doors in 1958, as has been done to a greater degree with the other four firms as they ultimately “transitioned.” In this regard, it addresses a very real and overdue need.

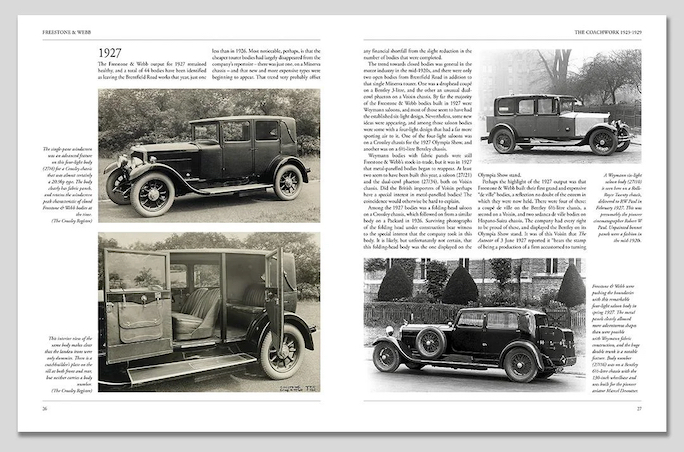

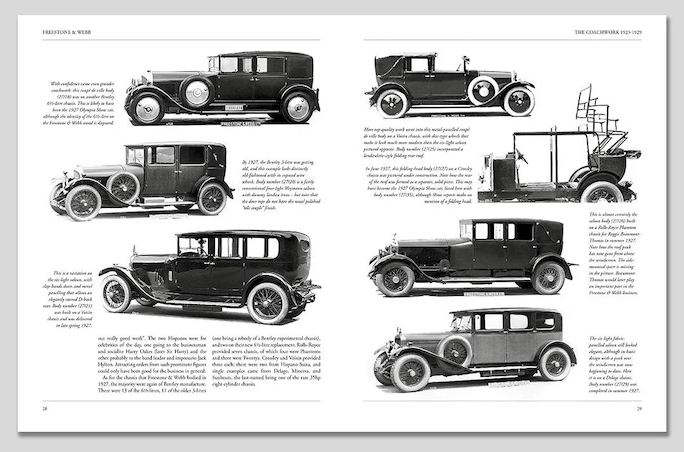

I’ve heard it argued that F&W’s standards of workmanship, fit, and finish, particularly postwar, weren’t quite as good as those of its competitors, but there was no arguing that they offered a lot of “bang for the buck.” Real bargains as it were. They alone among the Big Five continued to exclusively utilize traditional coachbuilding materials and methods of seasoned ash framework covered by hand-formed alloy panels finished in multiple coats of nitrocellulose lacquer, though it hadn’t always been so. Upon its founding in 1923, F&W were among the first to promote the Weymann method of deliberately flexible construction, which was initially quite popular, and continued to offer it until it ultimately completely faded from fashion a decade later. The Weymann construction method, its advantages and disadvantages, and the reasons for its ultimate demise are thoroughly explained.

There are a number of revelations in the book of which I’ve been unaware. Throughout its existence the company operated out of a purpose-built facility of ample size in what today we would call an early form of industrial park. Curiously, in all photos this facility is prominently identified across its façade as Unity Works; nowhere are the names Freestone and Webb to be seen. The reason for the name “Unity Works” remains obscure, but there must have been a compelling reason for its adoption and prominent display.

Author Taylor’s research is so thorough that for the first time that I’ve seen anywhere do we learn of the firm’s production in specific figures. In the course of its 35 years, it appears that slightly less than 1,000 bodies left the works, and of course, none at all from late 1939 until 1946. I say “it appears” because the company’s records for its first eleven years of operation have been lost, so the figures for those years are more or less educated conjecture, based primarily on the body numbers of survivors and the documented manufacture date of the chassis on which they are mounted. Translated into annual average production, the company rarely delivered an overall average of more than one car a week! For many years it was half of that! Freestone & Webb’s coachwork may have been considered to be bargains in comparison with their more prestigious competitors, but even so, the profit margin on each car must have been substantial in order to pay the rent, keep the lights and heat on, purchase materials, and meet payroll as work progressed through the months’ long process from contract design to finished automobile. We learn that the company’s best year was 1934, when sixty new bodies were constructed and delivered, only slightly better than one a week. That revelation was almost astonishing to me and tells me that with the possible exception of only a very few years, Unity Works likely had more than adequate space for all phases of its activities throughout its existence.

The details of each year’s production are displayed at the end of each relevant section in a table of columns that show ID no., Type, Date, Chassis type, and Chassis no. Those readers whose eyes glaze over when confronted with page after page of such dry data need not worry. The longest of these annual lists occupy only a single full page, with an additional column of ancillary notes continued across the gutter where necessary, but this occupies only about a third of a page. For those who love such comprehensive displays of historical data, don’t worry, you are not left out, either. The last chapter covers the period 1950–1958 and all the production details for those years are condensed into single, seven-page section. These tables make up for the lack of a comprehensive index and should actually make referencing efforts a bit easier as they are no more than a few pages away from photos and amplifying information in the text.

So how does this latest volume, devoted as it is to the craftsmanship of a single coachbuilder, compare with its predecessors in this series that cover specific models? It would be easy to say that it shares all of their pros and cons, only more so, and let it go at that. The overall production quality is commendably consistent, which is to be expected. My only real disappointment is with the historical b/w photos, which, as I’ve mentioned above, tend to be small; perhaps in some instances even somewhat smaller than in the previously published volumes. Again, this is an unavoidable trade-off, especially in this case where the author and publisher wanted to include as many examples of F&W’s diverse craftsmanship as possible. Simon Clay’s modern photography is beyond reproach. Time after time he gets the lighting just right for nearly ideal color saturation. No small feat as this has to be a major challenge in the British Isles, with their consistently inconsistent weather conditions, not just from day to day, but often from hour to hour.

Herridge & Sons play their cards close to the chest and don’t discuss future projects, but considering their now well established pattern of excellent volumes devoted to the art of automotive coachwork, we can only hope that there will be forthcoming volumes devoted to histories of the other four of the postwar Big Five-H.J. Mulliner, Hooper, James Young, and Park Ward. Now that will be a set worth having on one’s bookshelf!

I won’t spoil any more of the disclosures, particularly in regards to the firm’s more controversial postwar offerings, of which there are more than a few, other than to say they all get their share of attention.

Add this one (and its predecessors, if you haven’t already) to your library’s coachwork section. You won’t be disappointed.

Copyright 2022, Mark Dwyer (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

Nice work, Mark. Interesting subject.