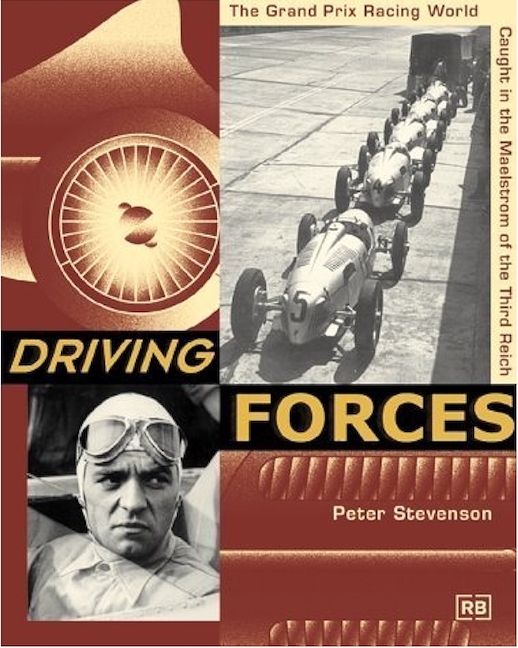

Driving Forces: The Grand Prix Racing World Caught in the Maelstrom of the Third Reich

by Peter Stevenson

by Peter Stevenson

The pre–WWII German Grand Prix cars remain among the most fascinating of machines for vintage motorsports enthusiasts. There is a shelf full of books on GP racing in the 1934–1939 period, but such was the horror of the World War immediately following that most authors have chosen to concentrate on the machines and race results, treading very lightly on political events. This book takes a different tack and looks at the human side of the story and the tension between the technical engineers who just wanted to race and the social engineers of the Nazi regime who wanted to rule the world.

Stevenson’s book reads like a novel (and has all the makings of a good movie if only a script reader discovered it!), with lots of fictitious dialogue, thrilling the reader with the personal struggles of the two principals, Rudi (the Rain Master) Caracciola and Bernd Rosemeyer, as they and the rest of the racing world were swept along by events that brought fame and fortune, but extracted a terrible price in the end.

The state-sponsored racing effort at first worked to the racers’ advantage, with quantum leaps in technology that made the French and Italian competition obsolete almost overnight and turned Rudi and Bernd, along with their teammates, into national heroes.

While pleased with the prestige earned by the racing successes, Hitler’s goal of working-class Germans happily zipping across the country’s network of autobahns in their Volkswagens was running behind and political screws began to tighten on the motor industry and the racing efforts. Gradually the pressure increased and political expediency began to dictate who should win a particular Grand Prix. This intolerable situation reached a breaking point as the Nazis demanded new speed record attempts during January of 1938. In a particularly vivid description of the autobahn runs that resulted in Rosemeyer’s death, the racing community comes to realize the pact they have made with the devil.

The personality angle is calculated to elicit sympathy from the reader, and it does—nothing wrong with that. In strictly historical terms, however, the book does not fully exhaust the panoply of nuanced and complicated relations between the Nazi dictatorship and the manufacturers but it does explore the propaganda value of motor racing which prompted, and sustained, Hitler’s interest in the first place.

Driving Forces is entirely different in concept than, for instance, Chris Nixon’s Racing the Silver Arrows—still a definitive volume on the subject—but it is exciting reading and does offer a less sterile perspective. I enjoyed it thoroughly. Stevenson has included an appendix of resource material for each chapter that will help those wishing for more information, and an epilogue telling how he first discovered those fantastic machines through the early postwar Floyd Clymer publications—an experience shared by many of us.

The Foreword is by Hans-Joachim Stuck, himself a racer (GP, F1) and son of Hans Stuck, who as principal Auto Union driver plays a prominent role in Stevenson’s account. A fold-out map of the world shows the locations for the 1937 season of Grands Prix. Photographically there is nothing obviously new, but the photo selection suits the text and the captions are quite detailed and list photo sources.

Stevenson nurtured an interest in sports cars ever since GIs returning from World War Two brought them to the US. During the course of volunteer work at the Briggs Cunningham Automotive Museum he was able not to only to get up-close looks at the racecars but also meet some of the visiting racing greats like Fangio, Moss, Railton, and Ireland. He has written on the subject for magazines and in 1972 published the book The Greatest Days of Racing(ISBN-13: 978-0684158549).

Copyright 2010, David Woodhouse (speedreaders.info)

A lengthy footnote by Sabu Advani:

We often make the point that no one book about a particular subject ever really turns over every stone. They all have different foci and priorities and the reader needs to understand them so as to be able to choose the one/s that best align with his needs and interests. As an example, consider the treatment of the 1936 GP of Tripoli in three books: Pritchard’s Silver Arrows in Camera, Reuss’ Hitler’s Motor Racing Battles and Stevenson’s.

They all convey the basic fact: that the race result was rigged as a result of government pressure. Pritchard keeps it simple and only says that Achille Varzi won when Hans Stuck (both Auto Union drivers) should have, but refrains from speculation by saying that the aftermath of “the story loses its verisimilitude.” Reuss’ more forensic approach devotes several pages to the episode, quoting extensively from memoirs (in this case Stuck’s and the notorious spinmeister Alfred Neubauer’s) and identifies the sources and elsewhere qualifies them. This is a critical point because memoirs prove nothing except that someone said something; they are nothing but one person’s uncorroborated viewpoint. By understanding who said what and when, the reader, like a juror in a courtroom, can weigh the arguments himself. Stevenson likewise devotes several pages to the story, using many of the same quotes Reuss does but does not identify them as such or attribute them, paraphrases them in the interest of literary tension, and does not tell the reader what is fact and what is conjecture. All three authors, Pritchard again being the most conservative, comment on the connection between Varzi’s embarrassment over the undeserved win and his subsequent heroin use and demise.

While the basic gist of the story is common to all three accounts, depending on the reader’s needs and expectations, the differences in nuance can become important! Also, only Reuss, being German, catches the double meaning in Stuck’s expression of frustration upon being denied the win: “I see. Greasing the Rome-Berlin Axis!” (Axis in German [Achse] means both axis and axle.)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter