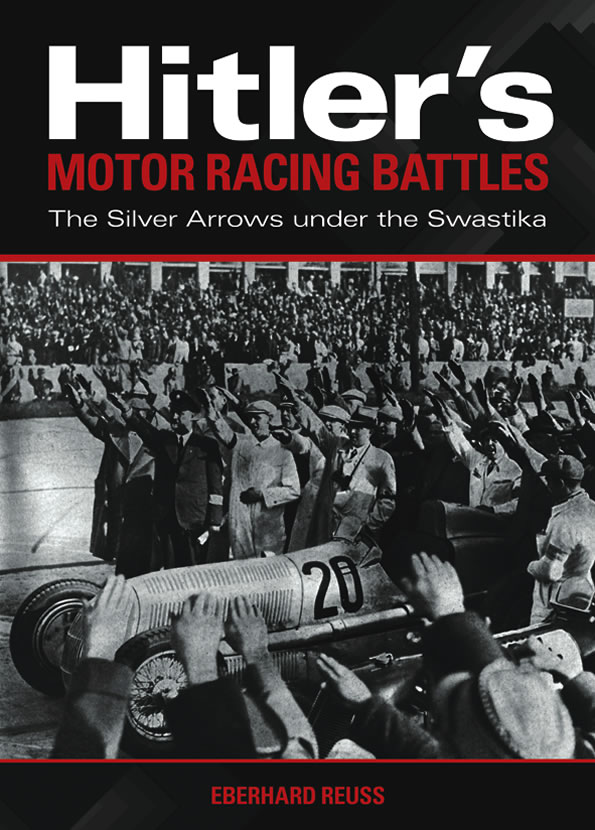

Hitler’s Motor Racing Battles: The Silver Arrows under the Swastika

by Eberhard Reuss

by Eberhard Reuss

“Let us correct the myths and perforce scratch the gloss of the racing legends. For beneath the silver that outshines everything there is a kind of brown stain, which can be attributed not to rust, but to suppressed history.”

Ever since producing a 1999 documentary on this subject for German television the author perceived a vacuum in the literature about the famous Auto Union and Mercedes-Benz Silver Arrows of the pre-World War Two period. Lots of books examine the cars and drivers, and while all provide some basic commentary about the political situation in Germany, none fully exhaust the subject of the “direct involvement of the Nazi regime in financing the teams and using them as naked propaganda.”

To this day, so many decades after the war, the subject of Nazism and the Third Reich remain—and understandably so—a particular German preoccupation both on the individual and the collective level.

In that sense it is fitting that this book was written by a German (b. 1957) because it is reasonable to assume that he arrived at his premises not just by abstract, detached academic reflection but is informed by the sort of general cultural subtext the foreign commentator would not be privy to. To those who fear such proximity to the subject must result in lack of objectivity one would say that the author was on the path to becoming a historian when he switched to broadcast journalism (which he still practices)—both disciplines require rigorous methodology and research. So, not only is Reuss (or, correctly spelled, Reuß) German, a historian, and a journalist—his specific interests lie in motor racing and he has produced many TV documentaries on its history. Just the right sort of qualifications to write a book like this.

The foregoing not withstanding, and without any intent to question his agenda but merely to illustrate the volatility of the subject and its subtext, let us quote a sentence from the penultimate chapter, p. 365, where Reuss says apropos of nothing in particular: “Incidentally, the FIA President today is Max Mosley [at the time pf publication; now Jean Todt], lawyer, one-time owner of a Formula One racing team—and a son of the former leader of the British Union of Fascists, the late Sir Oswald Mosley.” Undeniably true, but what does that mean other than that history casts a long shadow? Shouldn’t the sins of the forefathers be—just that?

Based on interviews with the remaining principals and/or their families (von Brauchitsch especially, also Meier, Pietsch, and Hermann Lang’s son) and other contemporaries, and research in previously un- or under-examined archives, Reuss has tackled this subject repeatedly in magazines and on radio and TV before writing, in 2006, the German version of this book. A primary point he makes is that, after the war, so many Germans professed to having been nonpolitical during Nazism, no matter that so many luminaries in the auto world held Party office or military rank, even if only honorary, and certainly willingly reaped the benefits of their association with the regime. Moreover, Reuss contends, being “nonpolitical” does not absolve one from “guilt by association” but on the contrary is an indictment itself.

Ideally, the reader’s interests would go beyond machinery and motor racing history. While there is plenty of that in the book, it is with constant reference to aspects of the human condition that are ultimately timeless. Sadly. The book is well and persuasively written but the degree of magnification oscillates between the sometimes pedantically detailed and the overly broad or irrelevant.

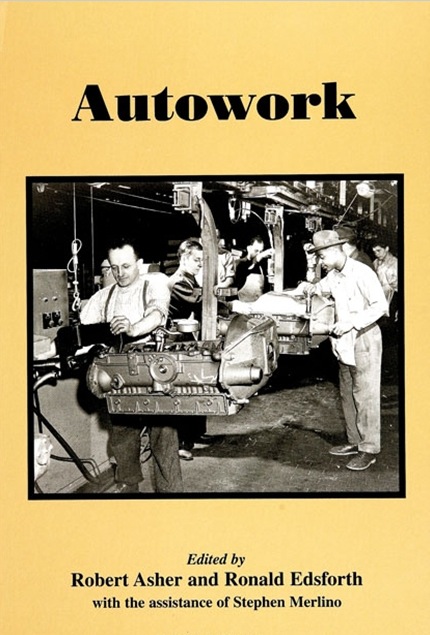

On the car front, as it were, the book covers motorsports in pre-Nazi Germany; Hitler’s friendly disposition towards sports of any kind, cars in particular; the state of German racing; and high-profile races, drivers, manufacturers, and functionaries. An extensive Bibliography, list of abbreviations (with translation), and a very nice Index round out the book. The photo captions are commendably specific, identifying all the people and locations. The photos are not necessarily new to the record but certainly this combination of political and car-specific imagery will be new to many readers.

Of note is the translator’s work whose additions in the form of explanatory chapter notes make the book significantly more accessible to foreign readers and presumes no prior familiarity with German history.

Won 2007 Motor Presse Club’s Motor Book of the Year.

Copyright 2010, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter