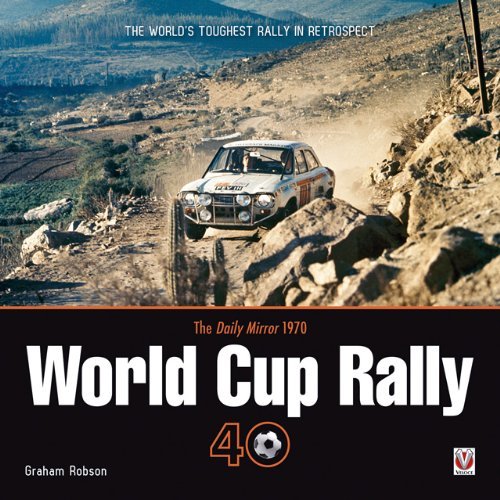

The Daily Mirror World Cup Rally 40: The World’s Toughest Rally in Retrospect

by Graham Robson

by Graham Robson

Any time you need to carry oxygen with you, you know you’re in for a trying time. Then and now the 1970 World Cup Rally is thought to be the toughest-ever rally. Six weeks, 16,000 miles, three continents, 17 torturous stages, elevations of up to 16,000 feet. London to Mexico by way of South and Central America. At one point the organizers worried if there would be enough cars left to see the rally through—of 100 starters, 23 finished. That its place in history has not been eclipsed has more to do with geopolitical issues (c.f. the 1973/74 fuel crisis, border-crossing restrictions, safety and regulatory concerns, funding cutbacks) than a lack of sporting ambition. There were other marathon rallies in that era—London-Sahara-Munich or London-Sydney to name a few—but the sheer scope, the quality of the drivers and the cars, and the physical and logistical demands make the 1970 WCR a thing unto itself. And Robson was there, as a traveling controller, except for the two weeks the cars were crossing the South Atlantic by boat and he rushed home to attend to his “regular” job at Chrysler UK who were probably wondering if their new hire had his priorities straight.

When we reviewed Robson’s last rally history book (Monte Carlo Rally: The Golden Age, 1911–1980) we made the point that Robson is most in his element with motorsports books. If he was ebullient in his writing about the Monte, which he also knew from personal experience, he ranks the 1970 WCR several orders of magnitude higher, describing it as making “all previous ones look second-rate” and himself as “totally fixated by the event which dominated my life . . . and has been unforgettable since.” Stuart Turner, who was Ford’s competition manager at the time seconds that notion in the Foreword he wrote for this book, saying “After many years of splendid work by my psychologist, I thought I’d finally gotten the WCR out of my head . . . ” —only to have Robson rekindle the obsession.

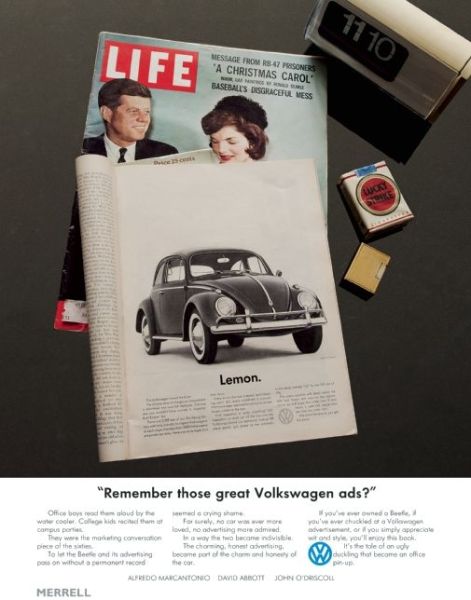

Written 40 years—and 10 football world cups (which take place every four years)—later, the book is intended as an homage. While London was a common rally starting point, it is the football connection that is the primary reason this rally started here, to connect the 1966 football HQ, London, to the 1970 HQ, Mexico City. The rally was sponsored by the British newspaper Daily Mirror which had been founded in 1903 by Alfred Harmsworth (later Lord Northcliffe), the owner of several newspapers, who early on threw his papers’ support behind high-profile events both to boost his own circulation and the causes he championed (1000 Mile Trial, transatlantic air travel, etc.). The Daily Mirror, incidentally, was initially conceived as a newspaper for women, run by women—“to be entertaining without being frivolous, and serious without being dull;” the WCR, like every decent rally, had a little bit of all of that . . .

Rather than just sifting through scrapbooks and news accounts, Robson went straight to those 1970 organizers, crew, mechanics, and colleagues that are still alive, only a few of whom gave him the cold shoulder. Beginning with the first-ever intercontinental rally, the 1968 London-Sidney (“far too easy!”), the book explains the why and how and who. The tales it tells may sound tall but probably aren’t. It really was a different time. From works-prepared and -supported rally cars to privately entered Rolls-Royces (which did not finish) it was a checkered field that took the checkered flag that April 19th. It’s all here, from getting lost to breaking down to handing over a piece of turf from Wembley Stadium to the football organizers at Aztec Stadium.

The text is enlivened by numerous quotes and anecdotes. Interspersed are such useful bits as a list of the prize money (cleverly the 1970 sums are related to other values of the time—such as the price of cars—and so give a sense for buying power), bookies’ handicapping lists, maps, even the rather pointless 1995 WCR “re-creation.” Each stage lists the fastest times; the photos (uncredited—grumble) are mostly of cars and drivers but also some local color. The 23 finishers are listed in all pertinent detail and the seven top finishers are further immortalized by brief biographical notes about themselves and the car. (The winning car is the one on the cover, a Ford Escort still owned by Ford today and trotted out for very special occasions.) The Index is a bit sparse but does list competitors (unintuitively all listed under “W”) but not cars—that data is given earlier in the book, pp. 60–62.

Most entertaining and engaging. Robson’s passion for the subject is palpable; if anything the book is too short!

Copyright 2015, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter