The Last Enemy

by Richard Hillary

by Richard Hillary

Why review an 80-year-old book? Because it is a classic and keeps getting reprinted. If you have your eyes set on a mint first edition, an antiquarian bookseller in the UK at the time of this writing will relieve you of of a cool £575/$731.

The continuing existence of books, in their traditional form of printed paper sandwiched between hard or soft cardboard covers, is coming under increased scrutiny as the world trends towards electronic media of all sorts and people become reliant on—addicted to, even—their various devices. The continuing popularity of such events as book fairs and the like suggests there will be scope for real books for some time yet, although it must be admitted that the audience does tend to be, shall we say, mature.

But regardless of whether you prefer to spend leisure time or assimilate information from either a backlit screen little larger than a playing card or a printed page, there is no doubt that books have a rather longer effective life than electronic media and can develop their own histories over time.

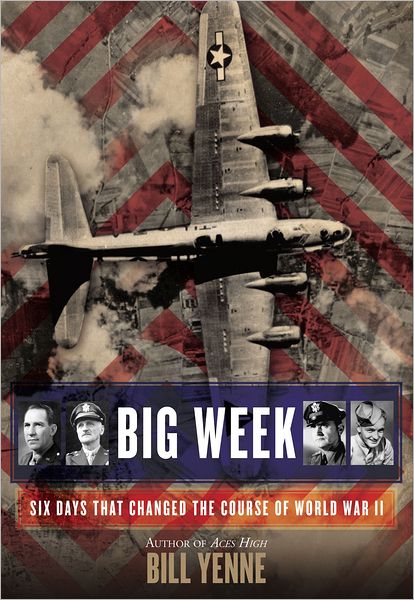

An air-to-air photo shot by the reviewer over Lake Wanaka (NZ) of a Spitfire Mk XVIe, at the time owned by the Alpine Fighter Collection and flown here by Nigel Lamb.

To wit, my copy of The Last Enemy, passed on by a bibliophile friend in Dunoon, Argyllshire (Scotland), is an example. Its title page bears, as well as an embossed address in Windsor Road, Ramsey, Isle of Man, an inscription to one T. Cherry: “A gift from Captain McLoughlan of Trinity inspection ship twin screw drive M.S. Hesperus. Oct 1943.” Subsequent owner from June 1981, Robert Roberts, is also a Manxman, and 43 years after that the book is resident in New Zealand, its dust cover long disappeared.

Both Hesperus and the original Ramsey house are easier to track down than the book’s donor or first owners. Built in 1939 in Dundee, the 202 ft 6 in steel motor ship was powered by two 8-cylinder 2SCSA oil engines by British Auxiliaries of Glasgow. She served the Northern Lighthouse Board, based at Oban and from 1964 at Granton, Edinburgh, before being sold 10 years later and finally broken up on the River Medway in 1985.

But on to matters aeronautical. Born in Sydney in April 1919 to an Australian government official and his wife, Richard Hope Hillary was sent to England at the age of seven to be educated, seeing his parents only during the summer holidays until he was 18. At Trinity College his studies came a distant second to sport, particularly rowing and flying in the Oxford University Air Squadron.

And travel. Hillary’s knowledge of French and German gave him relative flexibility of travel within Europe, and in July 1938 he embarked on a sponsored tour of Germany and Hungary with a collection of rowing friends to compete in a couple of regattas with the emphasis firmly on the social side.

He admits that the war came at the right time for him. Neglected studies were likely to catch up with him, and at the same time “the war solved all problems of a career.” “. . . We were disillusioned and spoiled. The press referred to us as the Lost Generation and we were not displeased. Superficially we were selfish and egocentric without any Holy Grail in which we could lose ourselves. The war provided it, and in a delightfully palatable form.”

Once things started moving, Hillary found himself in Scotland with some of his Oxford squadron friends, training on Harvards and getting offside with the Chief Ground Instructor over his innate laziness and knack for avoiding morning parades and lectures. Thanks to his flying instructor’s patience and consideration, however, Hillary managed to overcome his basic lack of mechanical aptitude and develop into a “quite moderate pilot.” While several from his course were posted on to fighters and others destined to be instructors, Hillary and two of his closer friends were sent to Old Sarum, near Salisbury, for Army Co-operation and Lysanders.

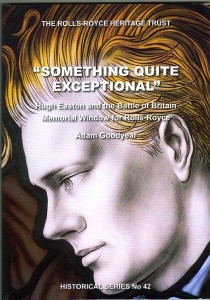

Then came Dunkirk and the sudden need for more fighter pilots as what was later called the Battle of Britain loomed. Hillary was posted to an OTU in Gloucestershire, flying Spitfires and describing some of the finer points of his training, then to his first operational unit, 603 (City of Edinburgh) Squadron at Montrose.

One of the benefits of a memoir written soon after events, when compared with a dry history written from numerous sources, is the value of personal descriptions. “Then there was Brian Carbury, a New Zealander who had started in 41 Squadron. He was six-foot-four, with crinkly hair and a roving eye. He greeted us warmly and suggested an immediate adjournment to the Mess for drinks. Before the war he had been a shoe salesman in New Zealand . . . There was little distinctive about him on the ground, but he was to prove the Squadron’s greatest asset in the air.” (Carbury’s final tally was 15½ confirmed kills, five of them on 31 August during the Battle of Britain.)

Carbury wasn’t the only New Zealander described by Hillary. Another was “of medium height . . . thick-set and the line of his jaw was square. Behind his horn-rimmed spectacles a pair of tired friendly eyes regarded me speculatively. ‘Well,’ he said, ‘you certainly made a thorough job of it, didn’t you?’”

And so enters Archibald McIndoe, the air force plastic surgeon to whom so many badly burned airmen owed so much. Horribly burned on his face and hands when his Hornchurch-based Spitfire was shot down in flames into the Firth of Thames on 3 September 1940, and picked up by the crew of the Margate Station lifeboat, Hillary became one of McIndoe’s Guinea Pig Club members, undergoing pioneering surgery to rebuild his face and hands. That wasn’t the only time Hillary had been shot down, but it was by far the most serious, and The Last Enemy opens with a harrowing account of his final Spitfire flight.

Almost half the book is taken up with a description of his treatment and convalescence, and ends with the realization that he could become a writer, justifying his fellowship with his “dead and to the friendship of those with courage and steadfastness who were still living.”

Later described as one of the classic texts of World War II and fully justifying its author’s intention to become a writer, The Last Enemy was republished in June 2018 by Penguin (right) as part of their series of six books commemorating the RAF’s centenary. This reviewer’s copy of April 1943 is the seventh reprint within a year of the original publication. In the US, the 1942 first edition was titled Falling Through Space.

Later described as one of the classic texts of World War II and fully justifying its author’s intention to become a writer, The Last Enemy was republished in June 2018 by Penguin (right) as part of their series of six books commemorating the RAF’s centenary. This reviewer’s copy of April 1943 is the seventh reprint within a year of the original publication. In the US, the 1942 first edition was titled Falling Through Space.

Alas, most reprints have been posthumous. Against McIndoe’s explicit wish, Flt Lt Richard Hillary returned to flying in November 1942 at 54 OTU, RAF Charterhall, Berwickshire, Scotland. One freezing night less than two months later he and his radio operator, Sgt Wilfred Filson, died in the crash and explosion of their Bristol Blenheim night-fighter. An annual lecture in his honor is held at Trinity College, Oxford.

Copyright 2024, John King (speedreaders.info).

The Last Enemy

by Richard Hillary

MacMillan & Co Ltd, London, 1942

224 pagesp, hardcover

List Price: OUP

ISBN 10: 0-88751-103-1

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter