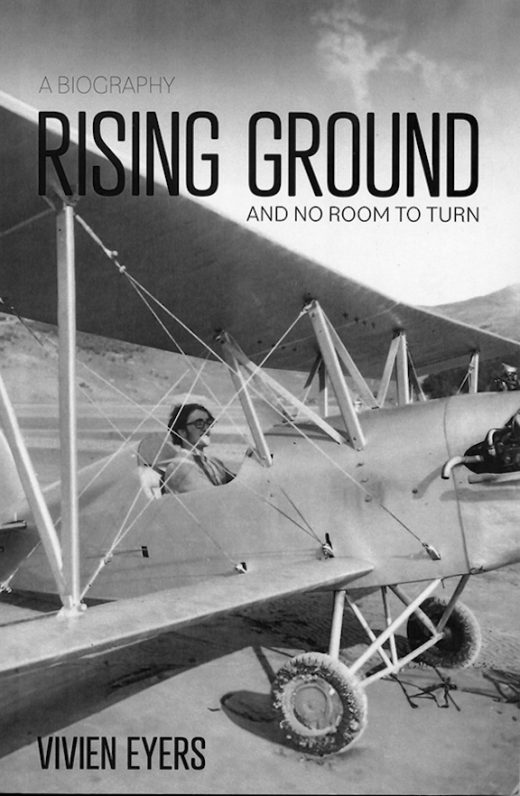

Rising Ground and No Room to Turn, A Biography

by Vivien Eyers

by Vivien Eyers

It would be fair to say that the name of Geoff Williams doesn’t loom large in aviation history, and few outside his native Otago, New Zealand would be aware of his considerable aeronautical exploits during the last three decades of the 20th century.

This is likely to change with the publication of Rising Ground, a detailed biography of the late Geoff Williams by his sister, Vivien Eyers. In setting straight the record of an unconventional airman, she has had full access to the records kept by somebody who never threw away any documents, even though his collection of personal items was sparse.

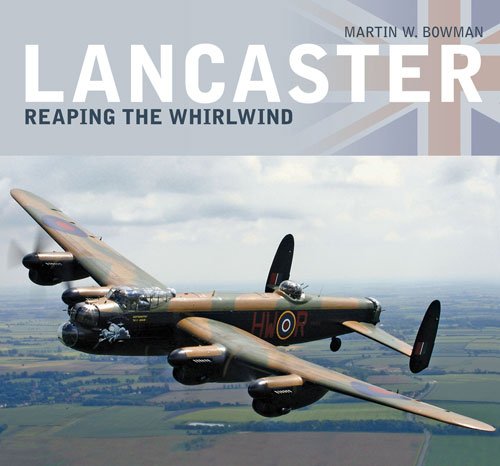

Born in 1949 as the second of three brothers to a rural schoolteacher, Geoff showed an early aptitude for avoiding what he considered unnecessary effort, scholastic or domestic, while at the same time being meticulous in everything he did or made. An early interest in aviation, fostered by his WWII Lancaster pilot father who maintained his interest in flying through gliding and setting up a local Air Training Corps cadet squadron, saw young Geoff spending all his pocket money buying materials to build model aeroplanes. These grew in size and complexity to the point where one of his last unpowered models had to be launched behind his mother’s Morris, only to disappear into the distance and not be found for some time.

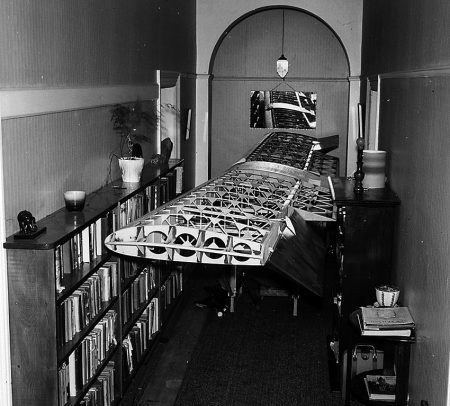

An older Dunedin house makes a good place to build the Mark Two wing.

From there it was a natural progression to even larger models which, powered by some sort of readily available and cheap engine of the VW variety, could carry a pilot. At the time the Williams family lived in a large house overlooking Dunedin’s Forbury Park, with spare rooms providing the space to construct a full-size fuselage and wings. Even after he moved out and went flatting in that hotbed of Otago University anarchic student accommodation, Leith Street (where after many long years of study he eventually earned a BA in Geography), the hall was long enough to build a one-piece wing, with fabric covering applied in the kitchen.

His flatmates tended to share either his flying ambitions or his liking for explosive chemistry experiments, something Geoff had also enjoyed from an early age, paying attention to those school subjects that he found interesting and useful. Some of his pranks led to reports of UFOs in Dunedin’s night skies, strangely candlelit apparitions slung an often safe distance below repurposed weather balloons or plastic-and-balsa envelopes, containing coal gas as the lifting medium. It should be pointed out, though, that he thoughtfully spared the family finances when filling his balloons by extracting the gas before the meter.

Mark One’s nose shows signs of an argument with a fence.

Geoff Williams built four single-seat aeroplanes, all to his own designs. Mark One (above), a biplane, was ready to fly in June 1970 and was transported by road to Papanui Inlet on the ocean side of Otago Peninsula. After some weeks of unsuccessful attempts to be airborne off the sand flats, the project was relocated to an airstrip at adjacent Hoopers Inlet where the farmer and his brother, who both flew Tiger Moths, encouraged this young inventive nascent aviator.

Mark Two is tied down for the night on an airstrip near Queenstown.

Mark One never achieved satisfactory flight beyond short hops, but at least the frequent mishaps and necessary repairs gave the opportunity to modify components before attention turned to Mark Two, a high-wing monoplane, completed in January 1973 and flown that April. Three years of trial and failure finally resulted in successful flight, even if its builder/pilot had only ever had a few hours’ flying instruction and never flown solo. Over the next 15 months he logged more than 60 hours in the air, often in short local flights around Hoopers Inlet but also further afield to visit family and friends at Five Forks and Ngapara.

Bureaucracy came calling in August 1974, having heard about the operation of an illegal aircraft and equally unlicensed pilot near Dunedin, and demanded that Geoff voluntarily dismantle the aircraft, which he did. A loophole: no one thought of banning any future aircraft . . .

Williams’s first three aircraft were underpowered. Mark Three lasted the least time of all.

Mark Three was a low-wing monoplane, ready in May 1977 after nearly two years of building, but it didn’t last long. After several test flights at Hoopers Inlet—and the inevitable repairs after mishaps caused mainly by engine problems—he was forced by inadequate engine power into the rough tussock on the southern approach to Lindis Pass. Mark Three was seriously damaged, but as usual Geoff was unhurt.

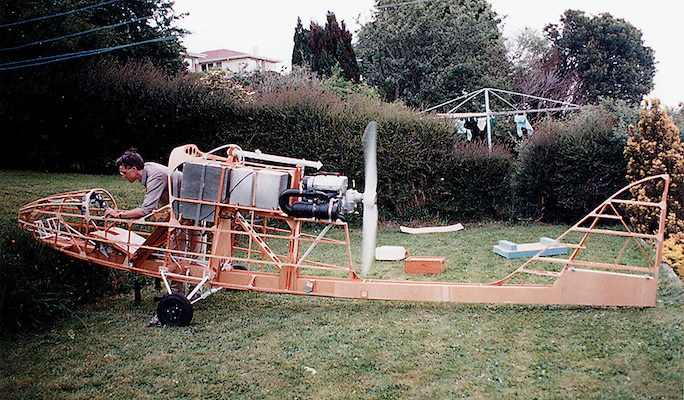

Finally convinced that he really needed a dedicated aero engine for reliable power, with time spent actually flying instead of constantly adjusting and repairing, Geoff designed Mark Four around a Rotax 447 in pusher installation, with a high wing and empennage carried on a low boom. Construction started in April 1988 with first flight on 24 January 1991.

Mark Four has an engine run in a Dundedin backyard. (The skeleton structure behind the hedge is not another airframe in the making but a clothesline.)

With the hangar at Hoopers Inlet no longer available for shelter, the Williams Mark Four had to be relocated to Monterey Station.

Geoff kept Mark Four under a row of macrocarpas trees at Monterey Station, near Lee Stream in the hills inland from Outram, from where he flew it extensively, typically at low level mustering sheep (or, according to rumor, aiming at rabbits with his home-made machine gun) and including a pass under the bridge across Lake Mahinerangi, during which he learnt about the habits of startled pigeons. In December 1991 he flew across Foveaux Strait to Stewart Island and back without stopping, south at 700 ft and return at wave height to conserve fuel, but later that decade his flying tapered off.

Using ground effect in Mark Four when northbound across Foveaux Strait with the Bluff hills hull-down on the horizon, a fishing boat can loom large.

Diagnosed with bone cancer in 2002, he made his final flight in Mark Four—to Taieri, Dunedin’s general aviation airfield—and died a month later. His fourth and last aeroplane was later legitimized as microlight ZK-JPA and still exists.

Rising Ground is a welcome slice of New Zealand aviation history, an entertaining book about an unconventional character who cheerfully disregarded inconvenient rules. It benefits from being written by his sister, somebody who knew him intimately, and thanks to proper editing and proofreading it is a cut above the average self-published book. Profits from sales go to Dunedin Hospice.

Copyright 2024, John King (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter