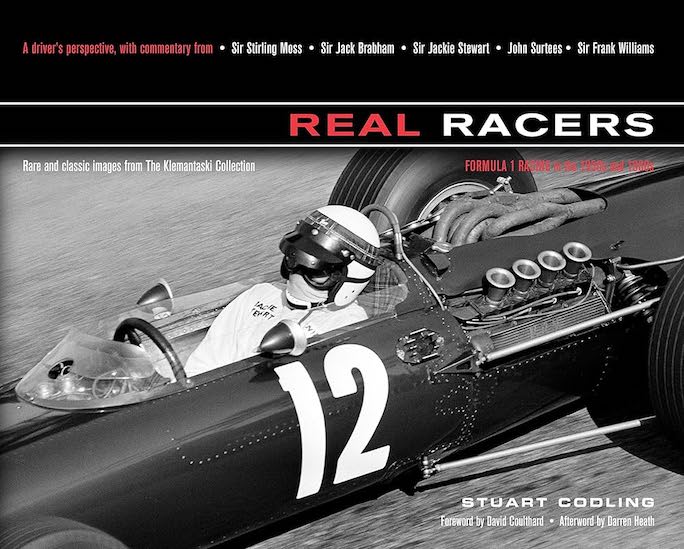

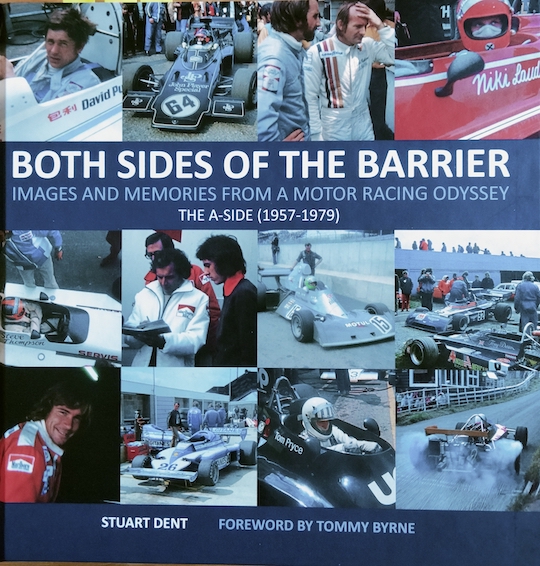

Real Racers – Formula 1 in the 1950s and 1960s

A Driver’s Perspective

Rare and Classic Images from the Klemantaski Collection

by Stuart Codling

The “driver’s perspective” alluded to in the title takes here the form of commentary by drivers who raced during those decades. This is a useful approach, and certainly lively, entertaining and direct—but it does not [want to??] put its finger onto the core of the issue: that of relative merits of the drivers. More than anywhere else in the book, it is David Coulthard’s (F1 driver 1994–2008) short Foreword that sort of/kind of casts a glance in that direction.

That this issue begs the question became nowhere more clear then when Michael Schumacher (b. 1969) bagged, in 2003, his sixth (of eventually seven) F1 World Championships, thereby eclipsing Juan Manuel Fangio’s (b. 1911) 46-year-old record of five. The talking heads in the media were/are besides themselves and crowned Schumi the Greatest Driver Ever. But is he? Schumacher, who is as much of a thinker as he is a racer, never sang that tune and politely deflected the matter, because he knows that in relative terms—allowing for the unwieldy cars, the brutal roads, erratic financing, nonexistent safety measures etc. etc. etc.—Fangio’s victories had been harder to come by. Not to mention that other matter, of Fangio’s 46.15% win/start ratio surpassing Schumacher’s 33.83%. The book that honestly and intelligently looks at those variables hadn’t been written by the time this one came out.

The title of this book is excerpted from a quote by Sterling Moss that is printed on the flyleaf: “There are very few real racers in the world, as opposed to mere racing drivers.” By adding another sentence to it, the back cover takes some of the sting out of it: “They’re the people who have a ruddy good go . . . really take it to a higher level.” Presumably the author counts Moss among the former, along with the other four still living drivers (Jack Brabham, Jackie Stewart, John Surtees, Frank Williams) and two deceased ones (Graham Hill, Bruce McLaren) whose thoughts appear throughout the book to accompany a story told largely in photos. It is stating the obvious to say that this distinction between “real racers ” and “mere racing drivers” will ruffle both readers’ and drivers’ feathers because at no point do the author or contributors trouble themselves to explain their parameters for dividing the field so conveniently. Arbitrariness is also already evident in a matter that may escape the casual reader but that a book reviewer cannot leave unaddressed: WHO decided in what order the one-page bios of the seven aforementioned contributors should be arranged? They begin with Moss who is neither the youngest nor the oldest, not the first name in the alphabet, not the most successful, didn’t have the longest career—you get the idea. The case of the other 33 drivers that play recurring roles in this book is straightforward enough: they are listed alphabetically, three to a page. They were selected for inclusion, says Codling, because they “participated in a significant number of F1 World Championship Grands Prix during the period.” It is probably not arbitrariness but sloppiness that four of their number—Gregory, Ickx, Siffert, Taruffi—are missing from an Index that otherwise appears to be thoughtfully divided by event, make of car, and people.

A race meet begins with the arrival of the racers, proceeds to practice and the race proper, and culminates in the finish. The book follows just that sequence, preceding it by a look at the drivers (see above) and adding to it related topics dealing with tactics, technique, driving experiences, and a PG-rated look at accidents. Codling, a print and broadcast journalist who joined the staff of F1 Racing magazine in 2001, begins each chapter with brief introductory remarks and then tells the story with extensively captioned photos interspersed with quotes that, in a generic manner, relate to the photos and overarching storyline.

If it is the name [Louis] Klemantaski in the subtitle that got your attention, notice also that it says “Collection.” Not all of the ca. 220 photos in this book are his. Other notably photogs whose work is showcased here are Nigel Snowdon, Peter Coltrin, Günther Molter, Yves Debraine, Alan Smith, Edward Eves, Robert Daly, Ami Guichard and more. Of the aforementioned names, it is the Klemantaski archive (ca. 60,000 images from 1936–1974) and the Snowdon archive (ca. 200,000 images from 1961–1987) that form the cornerstone of the over 500,000-strong Collection owned by world-renowned US Ferrari collector Peter G. Sachs. (One should think that a book that is all about the photos would actually list the photographers by page number of their work; no such luck).

Many of the photos are quite large (the book is in landscape format) and all are well reproduced. Many of them have not been published before. They invite—demand!—unhurried study. The Postscript by motorsports photographer Darren Heath seeks to describe the quality of Klemantaski’s photographs and it is particularly refreshing to hear a professional abstain from the sort of mindless fawning so often applied to a body of work like Klemantaski’s. Heath has no qualms about describing [some of] it as “not always striking in composition and content” but nonetheless possessing attributes that elevate it. In fact, the reader who buys the book primarily for the photos may well want to read this page first.

All the photos in this book, and of course many more, are available for purchase from the Klemantaski Collection as prints from original negatives; expect to pay $65–300 each, depending on size, sometimes even signed. To that end, and because the Collection does not have a catalog, one page in this book lists each photo’s reference number by book page.

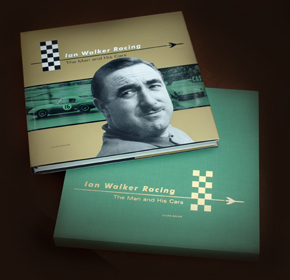

A special limited edition of 100 numbered copies, slipcased, and signed by the author is available from the Collection for $74.95.

Excellent photo selection, low price, nicely designed—buy one copy for the library and several more to wallpaper your house!

Copyright 2011, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter