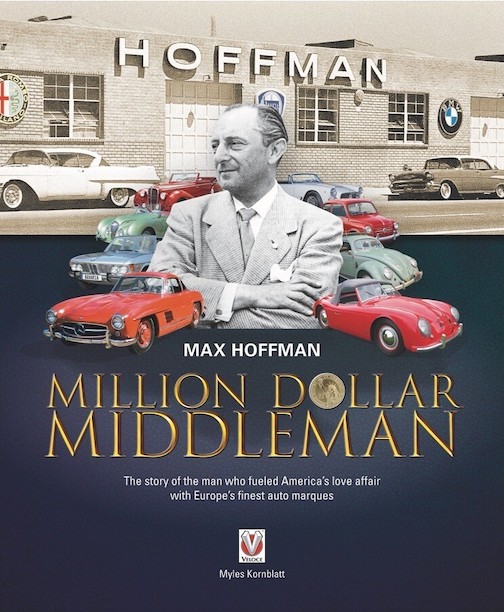

Max Hoffman, Million Dollar Middleman

by Myles Kornblatt

by Myles Kornblatt

“The manufacturer and distributor were often at odds because they both believed the other one wasn’t doing his share of the heavy lifting. In this case, it could almost be viewed that Lyons and Hoffman kept each other driven. If the relationship were friendlier, Hoffman may have eased his sales during Jaguar’s worker strikes. Or maybe Lyons would have reduced quotas in the midst of two US economic recessions during Hoffman’s tenure with Jaguar.”

This short excerpt hits on enough talking points to yield a full book, and they don’t even scratch the surface. But right away a key take-away here is that Hoffman engendered a love/hate reaction, certainly on the business side. The book says just about nothing concrete about Hoffman as a private person (character, values, temperament), which will make you think that there could have been more to say. And if not now, when? It’s not as if you could pick up another book for more detail—because there isn’t one. Except for the very occasional magazine feature, the Hoffman story has remained largely unexamined since that first noteworthy stab, in 1972 for Automobile Quarterly, by a young writer, Karl Ludvigsen. That Hoffman was still alive then (d. 1981) and talked to him may have been as much help as hindrance because Hoffman, ever the consummate salesman, was pretty much always in laurel-polishing mode. However, since Kornblatt’s book doesn’t claim to be a biography, no foul.

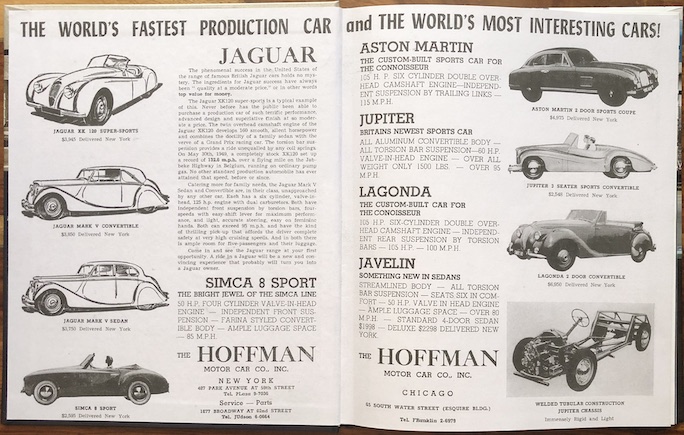

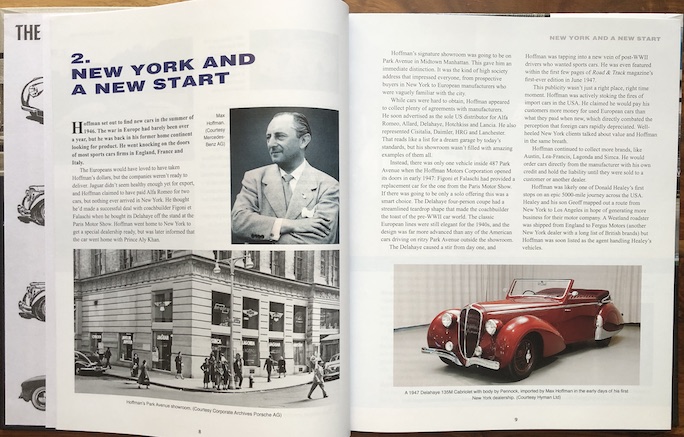

This is a slim book, which is neither here nor there—except, perhaps, in the context of its not so slim $50 asking price—but this ceases to be a neutral attribute the moment you suspect that brevity is the cause of ambiguity or lack of clarity that would have been avoided if only the author had sprung for a few more words. On the business side of things, for instance, an obvious but unanswered question is how Hoffman financed his start in business. Born 1904 he is introduced as an Austrian racer who retired young; his father owned a manufacturing company. It is plausible enough that Max was able to parlay the contacts he had made in the racing world into a civilian job in auto sales, but where exactly did he get the funding to set himself up as a dealer so soon after, and then in all the countries in which he bounced around before settling on/in the US in 1941? Or fast-forward a few years, to 1947 when, with only the profits from a few years of making metal-coated plastic jewelry in hand, he signs the lease for his first US showroom on Manhattan’s ultra-expensive Park Avenue, paying monthly rent of $3300, described here as “more than the average annual” US salary. That this amount is also more than double what similar-sized premises on nearby Automobile Row (where he would in fact open an additional showroom/service shop soon after) cost does demonstrate one thing: he was as much salesman as showman and he did have a knack for drawing eyeballs. However, converting prospects into paying customers was initially only possible by selling them vaporware—cars that hadn’t been built yet! This was such a rampant problem that the British Consulate in New York once was moved, after fielding more and more complaints, to express its misgivings to Jaguar, which brings us back to the excerpt above.

So, while this book won’t give all the answers, it certainly gives you a working knowledge of a key figure on the wholesale/retail/service side in the prosperous postwar years in the US. Hoffman did parlay that one single car he had in his first Manhattan showroom into a multimillion dollar business. More importantly, he was prescient in a way his competitors were not, first foreseeing and then stoking interest. That first car, a 1947 Delahaye, still exists and therein lies a reason this book exists: strolling a concours field Kornblatt realized that there are many Hoffman cars around—as well as many Hoffman stories but not all of them true, or not wholly accurate. Such as the exaggerated story of him waltzing into a Mercedes board meeting and throwing open a suitcase full of cash demanding a sports car, placing an order for one thousand 300 SLs.

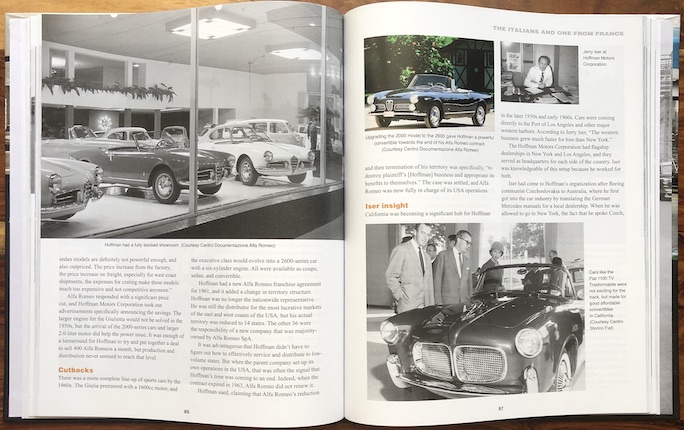

The emerging sports car scene in the US in the 1950s owes much to Hoffman’s initiative and you will come across his name in just about every book covering that era. Even though he primarily worked the eastern part of the US he did sell to dealers (and anyone who waved money at him) nationwide. The sheer volume of sales and PR he facilitated meant he had the ear of the European automakers. That’s the story this book lays out, and it does not shy away from examining why so many relationships ended in tears or in court or the occasional threat of a mob hit.

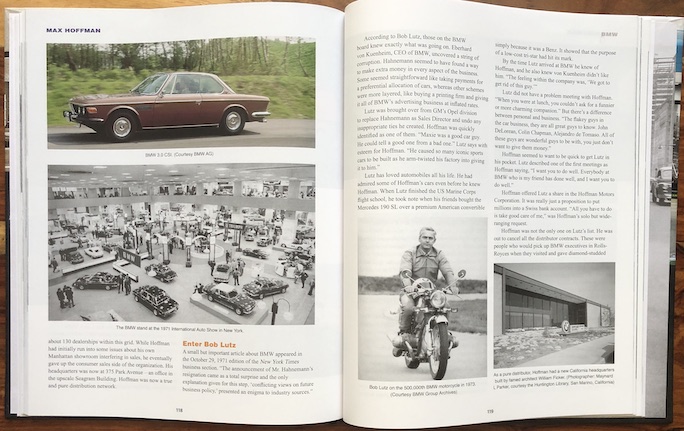

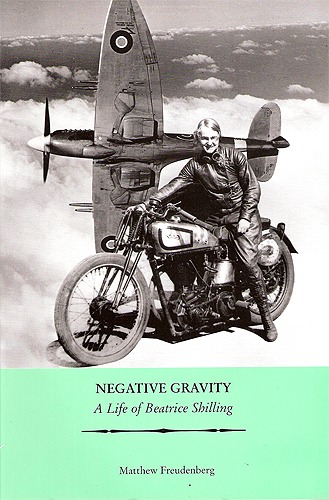

The fellow on the bike is Bob Lutz, never one to mince words: “Hoffman was beloved by any who did not know the way he did business: threats, intimidation, and bribes.”

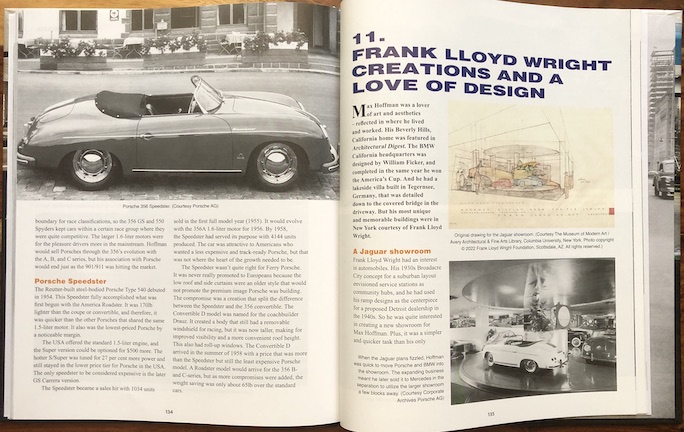

The story is told by marque (as opposed to strictly chronologically) which is a sensible choice for discussing Hoffman’s business strategies but it does require of the reader to maintain situational awareness because these different strands overlap and diverge fluidly. Occasionally, a “general interest” topic is interspersed, such as one about architect Frank Lloyd Wright who designed the showroom at 430 Park Avenue and later Hoffman’s private residence. Each chapter ends with an Epilogue, there are footnotes (and right on the page on which they are called out!), and an Index.

There appears to be great interest in this book, and rightly so, because the first print run sold out right away. Veloce is very good at reissuing books after a few years (sometimes many) but then usually as softcovers so don’t miss the opportunity to snag a hardcover.

While older Hoffman material may be hard to get your hands on there’s a brand-new (March 2023) analysis self-published by journalist and BMW expert Jackie Jouret, Max Hoffman and BMW, 1954–’75: The real story of BMW’s relationship with its controversial US importer . . . and how it nearly broke BMW (ISBN 978-1733387897). The title says it all, and the last bit is not an exaggeration! This is her 11th book on BMW history, she was an editor of Bimmer magazine and now a columnist for Roundel, which is a long way of saying that her case study is a much, much deeper dive, but of course isolated to BMW.

While older Hoffman material may be hard to get your hands on there’s a brand-new (March 2023) analysis self-published by journalist and BMW expert Jackie Jouret, Max Hoffman and BMW, 1954–’75: The real story of BMW’s relationship with its controversial US importer . . . and how it nearly broke BMW (ISBN 978-1733387897). The title says it all, and the last bit is not an exaggeration! This is her 11th book on BMW history, she was an editor of Bimmer magazine and now a columnist for Roundel, which is a long way of saying that her case study is a much, much deeper dive, but of course isolated to BMW.

Copyright 2023, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

Another Look

(Because we can)

Kornblatt has written of Max Hoffman mainly from the perspective of the automakers and their cars that Hoffman arranged to represent, importing and selling in the US. Quite simply that is because Kornblatt never had the opportunity to meet his subject who had been born in Austria in 1904 and died in 1981 in the US after immigrating to the US in 1941, fleeing along with his mom from the Nazis due to having Jewish bloodlines.

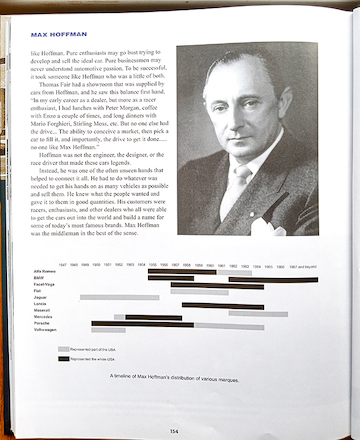

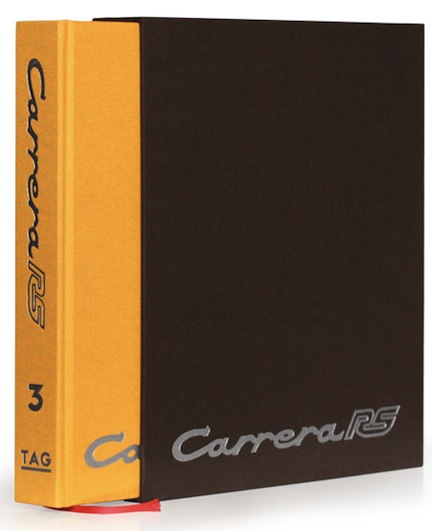

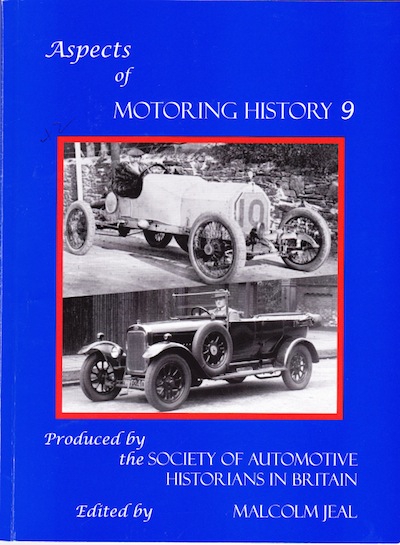

This most useful graph is beneath the portrait of Hoffman. It shows each make he imported and sold, indicating the span of years for each.

Chapters are organized by make/models essentially in the chronological order that Hoffman brought each into his New York City showrooms which he ensured were always located at fashionable addresses. Hoffman was, as Kornblatt writes, “the kind of duality that . . . makes for some of the best executives at the car companies. . . . He loved cars, but he made it clear that he was in business to make money.” Happily too, Max was an able and savvy businessman as his net worth when he passed, and the foundation established from it, attested.

Kornblatt’s Million Dollar Man has no bibliography per se but there are some footnotes that do cite references. Interestingly, they do not include any archive or library housing Hoffman’s paperwork or records. Surprisingly (or perhaps not), the most frequent is a specific issue of Automobile Quarterly as Volume X, Number 2 contains a 15-page article by Karl Ludvigsen. That article does contain many direct quotes from conversations Ludvigsen had with Hoffman. By the time that 1972 issue of AQ published, Hoffman had been in business in NYC and other locations for a quarter of a century selling various European-made vehicles although by then he was representing just one, BMW. Even that relationship was nearing its end as BMW was desirous of having its own company-owned business in North America.

The closing chapter of Kornblatt’s book tells of an event called Driven to America (DTA). The first was held in 2017 followed by two others in 2018 and ’19 respectively before Covid suspended it. DTA was organized to celebrate the history of Porsche and its genesis in coming to America thanks to Max Hoffman. Because Hoffman wasn’t involved with golf in any way, event organizers opted to not hold their event on any course. The inaugural was held at the Hoffman Center which is a “155-acre estate that had been turned into a nature preserve and wildlife sanctuary . . . set up by Ursula Niarakis, Max Hoffman’s former secretary and the president of the Marion & Maximilian Hoffman Foundation. It’s less than 12 miles away (mostly across the Long Island Sound) from Hoffman’s former Frank Lloyd Wright [designed] home.” As of fall 2023 DTA has not restarted but a number of fine images and information on Max Hoffman can be found on its website.

While Kornblatt makes it abundantly clear that Hoffman was a savvy and successful businessman and an astute judge of which types of cars would be attractive to American buyers, readers don’t gain much in the way of a sense of Hoffman on a personal level.

Hoffman’s success is reflected in the number of homes he had, each of which Kornblatt briefly describes. There was one in New York about thirty miles from Manhattan where he also had an apartment, another in Bavaria, one in Beverly Hills, and another in Florida. Along with an appreciation for fine cars, Hoffman obviously had a sense of personal style in his apparel as well as homes for the New York house was designed for him by Frank Lloyd Wright and George MacLean designed the Beverly Hills home. Wright also designed a special NY showroom for Hoffman.

As observed, Kornblatt never met his subject thus it isn’t too surprising that more aspects of Hoffman’s personal life and personality aren’t discussed in any detail. Kornblatt only offers passing remarks regarding Hoffman’s siblings and even his wife. Ludvigsen tells us a bit more about Marion Hoffman, relating that “Max had been going with the lovely girl from Connecticut for several years before he and Marion took the vows in 1956. She is a charming and intelligent woman, unavoidably dominated by her husband’s intensity when they’re together but blossoming when she’s on her own.”

The book is a straightforward read with, as said at the outset, emphasis on the various makes and models imported. A word to the wise: Veloce Publishing is located in the UK and while it does have a North American distributor, both have had their challenges keeping the book in stock, meaning you might want to turn to other sources.

Copyright 2023 Helen V Hutchings, SAH (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter