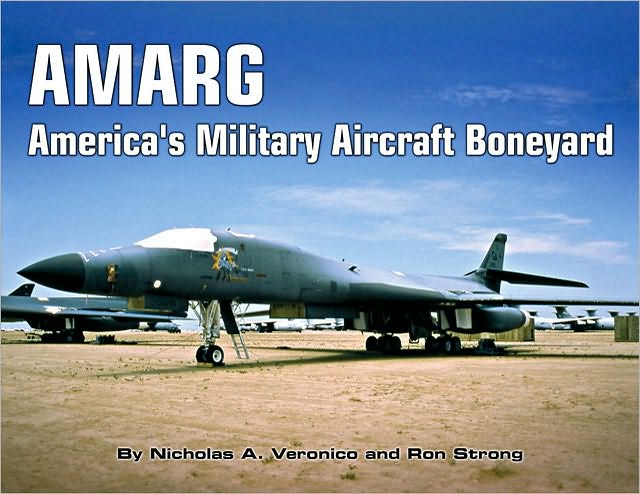

AMARG: America’s Military Aircraft Boneyard

by Nicholas A. Veronico, Ron Strong

by Nicholas A. Veronico, Ron Strong

“Traveling to the Sonoran Desert to view the military’s aircraft storage center has become somewhat of a sacred pilgrimage for aviation enthusiasts.”

America’s 2,448-mile “Mother Road,” U.S. Route 66, has a well-deserved reputation for its roadside attractions. Some are so small you miss them if you blink, some immensely large.

Imagine looking out the car window near Phoenix, Arizona in the late 1940s and seeing what must seem like a mirage: almost 5500 warbirds, some factory fresh, parked right by the road! And that site was only one of 28 all across the land, most of whose activities were either suspended or consolidated at the one facility that is the subject of this book.

World War II is over and over 33,000 of the 300,000 aircraft built in the US between 1940 and 1945 have returned home. What do you do with them?? The obvious answer—converting them for civilian use—had been tried before, after WW I, with mixed results. Flooding the market with cheap surplus planes had been so “successful” that it left aircraft manufacturers with no incentive to produce new ones and later came to be seen as a critical factor in America loosing ground in the 1920s and ‘30s to European advances in aeronautics.

A new plan then: store what is worth keeping and melt down what isn’t. If you bought pots and pans—or a car—after 1948, chances are it had aircraft aluminum or steel in it. Of the 33,000 aircraft mentioned earlier, the US government sold 20,703 at auction to be scrapped. (And there was real money to be made: the company that bought the 5483 aircraft parked by Route 66 paid $2.78 million for them and recovered 80 million pounds of metal and millions of gallons of av gas and oil worth $7.5 million!)

It is this sort of detail that sets this book apart. Except for internal documents there aren’t that many about military salvage/storage anyway and this book, short as it is, is pretty much the only one to develop that part of the story. It also lays out the whole post-1946 history of this one-of-a-kind specialized facility as well as the service-wide changes over time that resulted in an ever-widening scope—and commensurate name changes—of what since 1985 is known as the 309th Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Group (309 AMARG) within the Air Force Materiel Command. Divided into 29 areas it is today home to an ever-changing inventory of some 4400 aircraft and currently 13 space vehicles from all branches of the service and several federal agencies including NASA.

While the extensively illustrated book is presented as a “photo scrapbook”—something that its landscape format is ideally suited for—it really lays a solid foundation for understanding the many facets of the purpose of a strategic aircraft reserve. Unless you have occasion to think about such matters, many things here will surprise. Consider, for instance, that an aircraft that has to be able to be returned to flight status within 72 hours has totally different preservation requirements from a machine that is kept on long-term standby or one that is decommissioned to be a parts donor for the active fleet or one that is destined for museum use. Moreover, many more things go on at AMARG that one just wouldn’t think of: firefighting training, battle damage infliction and repair exercises (i.e. first shooting an aircraft to pieces, then understanding the damage, and then practice field repairs), or repurposing flyable aircraft with no foreseeable future fleet use as, say, target drones. Then there is SLEP, the Service Life Extension Program under which, for instance, current-inventory A-10 Warthogs are beefed up to double their service life to now 16,000 flying hours. AMARG also houses tooling for the B-1, B-2, and A-10. All of this is described and, as importantly, shown here.

Also covered is the process of applying/removing the multi-layer protective cocoon—the key factor in outdoor storage—as are the criteria and procedures for inventorying and processing aircraft depending on what fate has been assigned them. The well-reproduced photos come from a variety of sources and are extensively captioned, often with information specific to the airframe shown. Among the gems are several period photos in color. Not all photos are dated, which is not terribly important but could be interesting to someone who wants to get a sense for the changes at AMARG over time (or, just possibly, recognizes a plane they may have flown), especially in chapter 3 “Along the Storage Rows” which wildly skips around between types and vintages of aircraft. Included are rotorcraft, civilian airliners, and the only surviving Navy airship gondola in the US, but of space vehicles only a missile is shown.

One thing the text does not make clear is that AMARG isn’t just a repository for US aircraft but offers “maintenance and regeneration capabilities for Joint and Allied/Coalition warfighters in support of global operations” which accounts for the presence of non-US aircraft at the facility in addition to the several MIGs once used by a secret USAF squadron to train US personnel or the Tornados donated by Germany to the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force.

Appended are author bios, a list of the 4288 items at the facility as of 2009, and information about touring AMARG (note that foreigners are admitted even though this is an active Air Force base) as well as the Pima Air & Space Museum, the 309th Memorial Museum, and the Titan II Intercontinental Ballistic Missile silo, all in or near Tucson. There is a Bibliography/Reading List but no Index.

No matter where your aviation interests lie, this book shows you things you wouldn’t even see if you did take the tour (right). The year after it was published the Boneyard became the setting for yet another activity. Beginning in the summer of 2011 several dozen contemporary global artists began using entire planes or parts thereof as their “canvas” in a project fittingly called Return Trip. Although no such announcement has been made one should think a catalog or book about that seems likely.

No matter where your aviation interests lie, this book shows you things you wouldn’t even see if you did take the tour (right). The year after it was published the Boneyard became the setting for yet another activity. Beginning in the summer of 2011 several dozen contemporary global artists began using entire planes or parts thereof as their “canvas” in a project fittingly called Return Trip. Although no such announcement has been made one should think a catalog or book about that seems likely.

Won a 2010 Honorable Mention by the Military Writer’s Society of America.

Copyright 2012, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter