Lichtenstein, A Retrospective

by James Rondeau and Sheena Wagstaff

by James Rondeau and Sheena Wagstaff

Who would have thought that The Three Stooges would be cited when discussing etymology? In their 1935 short, Hoi Polloi, the phrase is used to designate the few, the upper crust, the hoity-toity, rather than its true definition, “the many.”

Over time, “hoi polloi” has become a contronym, a word or phrase that holds opposite meanings. There are two types of contronyms: The first is really a pair of homophones, two words that are spelled the same but have distinct etymological roots (“cleave”); the second type, polysemies, are words that have two distinct but opposing meanings, probably because of initial misuse and continued practice, but have the same root (“sanction”).

Through the decades “hoi polloi” has kept its original meaning, the common folk, but it has also acquired, due perhaps to a legion of Stooges fans, its opposite meaning—the few, the privileged. Not long ago, the NPR grammar maven Mignon Fogarty discussed this term and mentioned that some dictionaries are now citing both contrary definitions. A few days after listening to Fogarty, I found, in The New York Times arts section, an article that used “hoi polloi” to mean the beau monde. So today we are witnessing the birthing and advancement of a prevailing example of polysemy.

I bring all of this up to suggest that the American painter Roy Lichtenstein (1923–1997) can be appreciated by the hoi polloi—using both of the opposing meanings. In his The Painted Word, a scathing critique of the art world after World War II, all of those isms, Tom Wolfe contends that despite the critical reverence bestowed upon Abstract Expressionism and Action Painting, these works were really not doing all that well in the marketplace. He paraphrases Jackson Pollock: “If I’m so terrific, why ain’t I rich?”

Wolfe argues that art theorists, in collusion with museums and dealers, promoted artists whose work exemplified the theorists’ ideas (Morris Lewis with his stripe paintings that followed Clement Greenberg’s ideas is an example) rather than the artists who demonstrated accomplished technical and drafting skills. He goes on to say that when Pop Art hit the scene, the market found an uptick, and he reasoned that this was because collectors wanted something recognizable, something real, something comprehensible, to hang on their walls, and, simultaneously, because of the postmodern ironies of Pop, they could still retain their regard for obtuse theory.

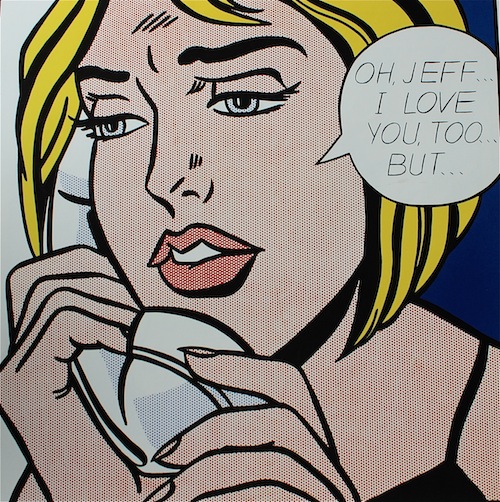

Lichtenstein is a perfect example. Who can resist the charm and immediate gratification of comic strip panels, lovelorn maidens and jet fighters, blown up on wall-size canvases? The hoi polloi, the many, can admire these works and bathe in the warm waters of nostalgic recognition, and the hoi polloi, the few, can feel cocksure because they are in the know, because they alone can appreciate the subtle theoretical doctrines, thus showing their erudition and sophistication. And this current book is a fine tribute to this artist and his work.

Graphically the book, an exhibition catalog for The Art Institute of Chicago and London’s Tate Modern, is without fault. The plates are large, elegantly printed and clearly labeled, making them easily referenced when the introductory and scholarly texts are supported by pictorial examples. They are grouped into the various series of Lichtenstein’s work, Early Pop, War and Romance, Mirrors, Nudes and the others, roughly chronological, and, except for the last section, Works on Paper, they are distributed one to a page. The colors ring true, and despite the necessary reduction in scale, one can assimilate Lichtenstein’s methods and ideas—or at least nearly so because no book can replicate the experience of standing in front of an 8 x 10-foot canvas.

One only casually familiar with Lichtenstein’s work may be pleasantly surprised by the extent of subject matter found in this catalog. His brushstroke series is a sly, humorous dig at abstract expressionism; his nudes produce a paradoxical meld of innocence and eroticism; his take on the modern masters, Picasso, Cezanne, Mondrian, show both homage and wit; and his transformations of classic Chinese landscape painting are unexpectedly serene. Included too are the free-standing sculptures. Perhaps Lichtenstein became trapped in the expectations of the art world to adhere to his methodology, the Benday dots, the sharp, comic book outlines, or trapped in the promulgation of his franchise, and the subsequent sameness may induce tedium for some. But of course this cannot be a criticism of the book.

Along with the acknowledgements and the introductory material, Lichtenstein contains nine academic essays. Each deconstructs a particular series, offering insight and theory. In his essay on the Landscapes in the Chinese Style, Stephen Little tells us that “while multivalent ironies are present in Lichtenstein’s art and resonate throughout the works in the series, he believed that ‘irony alone never makes a painting.’” Sheena Wagstaff believes that “an examination of Lichtenstein’s great Nudes reveals a fascinating story: a spiral return not just to comic-book sources…but also to two of his mentors, Pablo Picasso and, to a lesser extent, Henri Matisse.” Yve-Alain Bois discusses the Entablature series in its relationship to the minimalists Kenneth Noland and Donald Judd. These essays, although academic and theoretical, are both readable and lucid. Source notes given at the end of each essay show the depth of the scholarship.

The presentation of the essays is attractive. Each page is divided vertically in half, the text on one side and various illustrations, nicely spaced, on the other. The image on the cover of the book—there is no dust jacket—was well chosen: A detail of the 1965 Seascape, a panel of blue Benday dots interrupted by white, yellow stripes, a swath of red Benday dots and black wave patterns. A single word, “Lichtenstein”, black, bold and in capitals, cuts across horizontally, fully, nearly centered.

Overall, the presentation is first-rate, complimenting the content to a high degree, a suitable appreciation for this coolly ironic American artist. Copyright 2012, Bill Wolf (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter