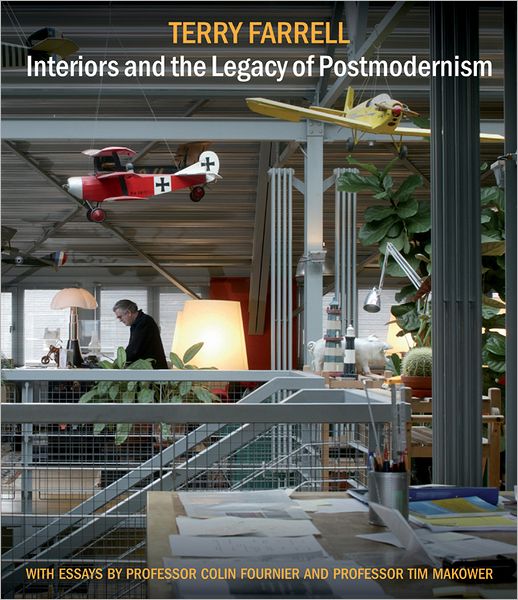

American Military Aircraft 1908–1919

“During the decade from 1909 to 1919, obtaining suitable aircraft was a constant struggle and sometimes simply impossible. Few domestic designs fully met requirements and many fell far short or were complete failures.”

Taxonomy is a field not often associated with, say, military aviation history, but if one stops for a moment to consider the need for designation systems, serial numbers, and so forth, one realizes just how critical such data is for certain aspects of the study of this niche of Clio’s realm. Among the earliest examples of this might be James C. Fahey’s U.S. Army Aircraft (Heavier-Than-Air) 1908–1946 published a year after the end of World War II. Fahey may be better known for his series The Ships and Aircraft of the United States Fleet, which began in 1939 and ended with its 8th edition in 1965, with the Naval Institute Press taking over the series in 1972 with various editors, most notably Norman Polmar.

In U.S. Army Aircraft, Fahey was probably among the first, if not the first, to provide a catalog of the aircraft of the United States Army from its beginning in 1908 to the time of publication, 1946. He gave consideration not only to the aircraft of World War II, but also to those prior to and during the Great War as well as the interwar years. The aircraft designation systems of 1919–1924 and the one in use since 1924 were both provided, with as much detail as could be crammed into the 64 pages of the 6 x 9” pamphlet format. The wonders of aircraft manufacturer code letters and block numbers were also first committed to paper for the general public, much to the benefit of those interested in the taxonomy of American military aircraft.

In 1963, the first edition of United States Military Aircraft Since 1909 (Putnam Aeronautical Books) by Gordon Swanborough appeared, followed in 1968 by the first edition of his United States Navy Aircraft Since 1911 (Putnam Aeronautical Books). In later editions, Peter M. Bowers would join Swanborough in editing the series, with the last editions appearing in 1989 (Smithsonian Institution Press) and 1990 (Naval Institute Press), respectively, which is really an astonishingly long lifespan. In 1979, U.S. Military Aircraft Designations and Serials, 1909 to 1979 by John M. Andrade was published (Midland Counties Publications, reprinted 1997), being a combination of the Army, Navy, and Air Force (along with the Coast Guard and post-1962 Department of Defense) designation systems and the serial numbers for American military and naval aircraft to that date.

Someone with an interest in those early days of American military and naval aviation might find that all that glitters is not necessarily gold. Fahey, for instance, provides a listing of the aircraft procured by the Army up to the entry of the United States into the Great War. Interestingly, there are serial numbers included in the listing, the lowest serial number being given for that model when more than one was purchased. Fahey also covers the aircraft the American Air Service included in its World War I production program along with the aircraft that the American Expeditionary Force purchased from the French, the British, and the Italians during the war. Andrade duplicates much of this information while adding additional data. Swanborough (and Bowers), on the other hand, give relatively little attention—and space—to the aircraft of this period.

In 1970, the author of the present book, a mechanical engineer from Ohio, began self-publishing his Encyclopedia of U.S. Military Aircraft. It was to consist of two parts, the first one dealing with those aircraft procured prior to 6 April 1917, the date the US entered the Great War on the side of the Allied Powers. The second part would cover the World War I production program. Each part would be in the form of individual volumes covering the aircraft in alphabetical order by manufacturer. The format was similar to the Fahey books: pamphlet-style 6 x 9″ softcovers.

In 1970, the author of the present book, a mechanical engineer from Ohio, began self-publishing his Encyclopedia of U.S. Military Aircraft. It was to consist of two parts, the first one dealing with those aircraft procured prior to 6 April 1917, the date the US entered the Great War on the side of the Allied Powers. The second part would cover the World War I production program. Each part would be in the form of individual volumes covering the aircraft in alphabetical order by manufacturer. The format was similar to the Fahey books: pamphlet-style 6 x 9″ softcovers.

Part I consisted of four volumes published from 1970 to 1974, beginning with Aeromarine and ending with the Curtiss JN-4, JN-4B, JN-4C, R-2, R-4, and Twin JN aircraft. Part II consisted of three volumes, the first appearing in 1972 and the last in 1975. The first volume began with the Avro 504 and the third volume covered the Curtiss Jennies. The amount of research evident in Casari’s work was as mind-boggling as how much of it he managed to cram into these little books ranging from 64 to 152 pages.

However, after the third volume of Part II appeared in 1975, the coverage only having reached the letter “C,” a long silence ensued. Had Casari abandoned the project, or run out of resources, or taken a temporary break? Those who had all seven volumes counted themselves fortunate because they were the most authoritative, accurate, and best sources on the era available.

It should be noted that even today, 40 years later, the historiography of this period is relatively thin. Any examination of the period still begins with Juliette A. Hennessey’s monograph The United States Army Air Arm, April 1861 to April 1917 (USAF Historical Studies No. 98, USAF Historical Division) first published in 1958. The four volumes of The U.S. Air Service in World War I (The Office of Air Force History), edited by Dr. Maurer Maurer, first released in 1978 and 1979, are primarily a collection of documents regarding the operations of the Air Service of the AEF, which are often more a potpourri of material slapped together than an edited set of documents, much less a coherent history of the Air Service during the Great War. One hopes that the Air Force plans on doing better when the centennial of the AEF and its Air Service arrives in a few years.

Two recent noteworthy additions to this historiography are Hat in the Ring: The Birth of American Air Power in the Great War (Smithsonian Books, 2010) by Dr. Bert Frandsen, a member of the faculty of the United States Air Force Command and Staff College, and Stalking the U-Boat: U.S. Naval Aviation in Europe During World War I (U. of Florida Press, 2010), by Geoffrey Louis Rossano. Hat in the Ring is primarily a study of the 1st Pursuit Group of the AEF Air Service, using the group’s operations as a means to examine the roots of American air power that would bear fruit during World War II as well as an examination of the evolution of the fighter aircraft used by the group, beginning with the Nieuport 28 and then the SPAD XIII.

Stalking the U-Boat focuses primarily on the trials and tribulations of the junior officers who were usually given rather broad, even vague, missions and orders, yet managed to establish 27 naval air stations by the time the Armistice was declared. As Rossano demonstrates, time and again these junior officers overcame adversity and challenges, becoming creative and often innovative in their solutions to perplexing and often seemingly impossible tasks. As with many members of the Air Service’s 1st Pursuit Group, these junior naval aviation officers would play important roles in the Second World War, commanding the aircraft carriers that would carry much of the weight of the war in the Pacific.

Which brings us to the present book. “Masterpiece” is a term one should use not only sparingly but reserve for only those few works that are so extraordinary as to stand alone as a pinnacle of achievement. Casari’s American Military Aircraft 1908–1919 is, beyond doubt, a masterpiece of historical research.

From piecing together the serial numbers of Army and Navy aircraft prior to the Great War, to sorting out the aircraft of the World War I production program, Casari has managed to assemble a mass of information unlike anything else for this era. Although he modestly suggests that the information was always there in the various archives, readily available for anyone willing to make the effort to delve into their depths, it was he who did the digging, sorting out seemingly unrelated bits of information and seeing the connections, making sense of the sausage-making of the production program—thus discovering the many reasons that it failed to find success in 1917/18.

From piecing together the serial numbers of Army and Navy aircraft prior to the Great War, to sorting out the aircraft of the World War I production program, Casari has managed to assemble a mass of information unlike anything else for this era. Although he modestly suggests that the information was always there in the various archives, readily available for anyone willing to make the effort to delve into their depths, it was he who did the digging, sorting out seemingly unrelated bits of information and seeing the connections, making sense of the sausage-making of the production program—thus discovering the many reasons that it failed to find success in 1917/18.

Along the way, Casari also found the means to challenge many existing interpretations for the failures of the production program, making it clear that despite the Congressional investigations and the Air Service’s own unpublished postwar eight-volume manuscript, The History of the Bureau of Aircraft Production, that there was far more nuance to the failures to produce aircraft as intended during the war than is usually offered.

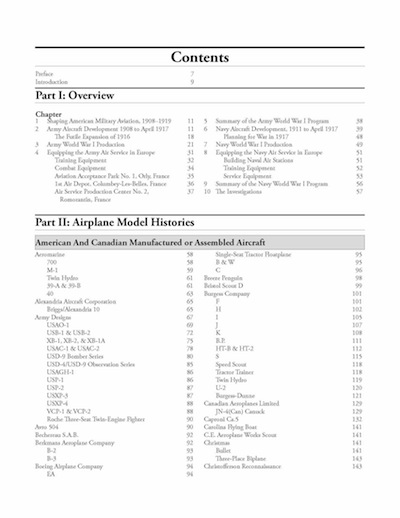

This 7 lb, large-format book consists of two parts. Part I is an overview of American military aviation from its beginning in 1908 to the end of the Great War, concluding with the summaries of the Army and Navy aircraft production programs and the postwar investigations of 1919. The chapters range from just a few paragraphs to several pages, a great deal of information being crammed into just 57 pages.

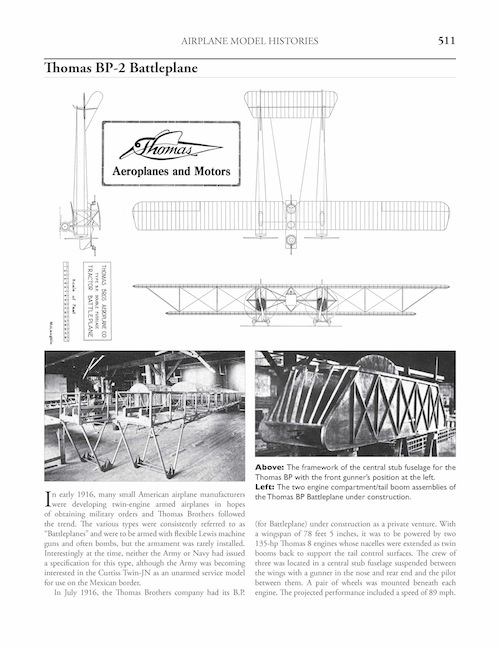

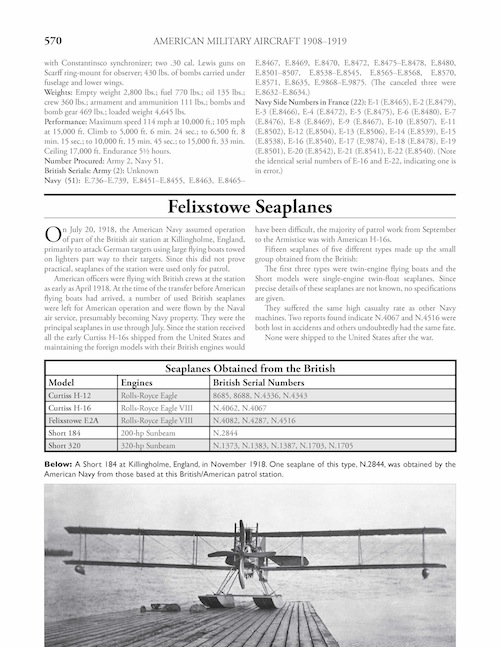

Part II, spanning over 600 pages, presents by manufacturer and then model all aircraft actually acquired or even only considered by the Army and Navy, and is further divided into aircraft made or assembled in North America and ones procured from England, France, or Italy.

The hundreds and hundreds of photographs are nothing short of stunning, and Casari, correctly, in view of the encyclopedic aspirations of this book, allowed the occasional poor photo rather than showing none at all.

The 14 Appendices are a goldmine of information. Appendix A, for instance, provides a complete listing of Army serial numbers from 1909–1919, which was the genesis for this work. That no such list existed before Casari began his work is due in great part to files being discarded by a government agency prior to its move to another location. That Casari managed to reconstruct these numbers is, in and of itself, a noteworthy feat, and that he then successfully matched serial number to constructor and model is simply incredible. Appendix B does the same for Navy aircraft. The book closes with 8 pages of color drawings, a “Photo Addendum,” and a proper Index.

This book is a testament to the perseverance, persistence, and dogged determination of someone wishing to “do history right.” It should become the standard reference for this period of American military and naval aircraft for years to come. It may have taken five decades of effort for this book to finally see the light of day, but we should be very grateful that Casari stayed the course and that a publisher whose motto is “aviation history books for enthusiasts by enthusiasts” has made it possible for his dream to come true.

Copyright 2015, Don Capps (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter