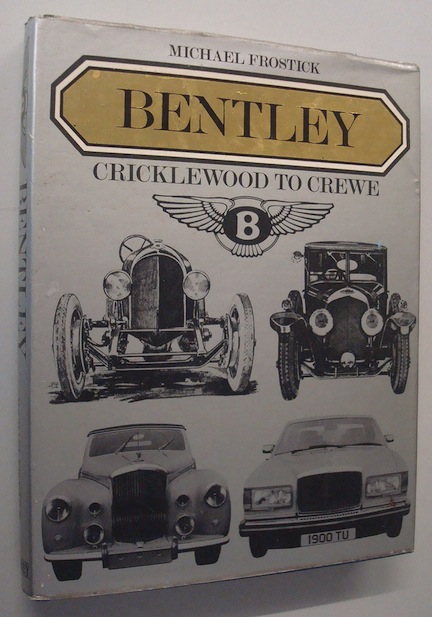

Bentley – Cricklewood To Crewe

It’s hard to decide whether to put this remark at the beginning or the end; it’ll hurt either way: Yet another Bentley book might seem too many even to the most avid enthusiast; for what is there to say that has not been better said before— usually more than once?

Phew. No matter how you slice it, the author really is known for a “cut and paste” approach to cobbling books together, could hardly have hoped for universal acclaim. He found in this reviewer a sympathetic reader—but who also enumerated a multitude of problems. As long-time editor of the Bentley Drivers Club magazine, Review I do know my way around Bentleys and in the 30-odd years since first evaluating this 1980 book I have not had occasion to change my mind about it. Still, the book deserves to be part of our archival record.

***

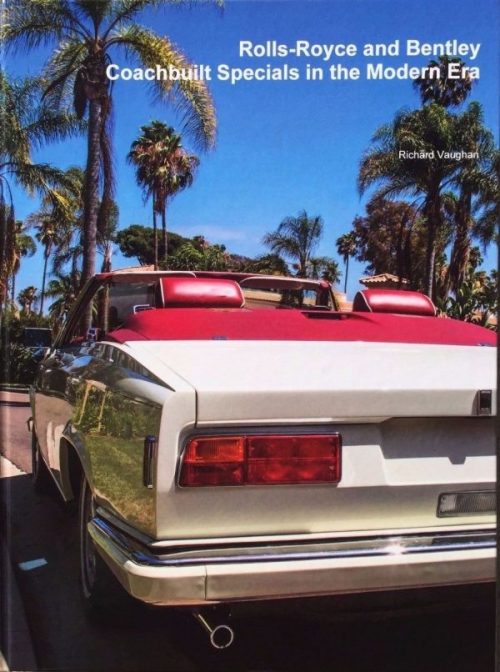

This strangely disturbing book gets off to a curious start by presenting, cameo style, portraits of Sir Henry Royce and W.O. Bentley on facing pages, a juxtaposition that has not been seen before. Perhaps it will not be seen again.

The author at least has the tact to place the two men facing outward, away from each other, and this rather sets the theme of the book. Which is: the story of a make of motorcar called Bentley as revealed by the records of successive companies of that name, the contemporary press, personal recollections and a comprehensive if (necessarily) dated bibliography. The author’s recourse to original source material makes this book the most authoritative there is on the old company, and his handling of his material ensures that the result will be found provocative by some of his readers.

The book is divided into parts and, unlike the curate’s egg, is good in all of them. Part I deals with The Men, meaning both the founders and their successors. What distinguishes this portrayal of W.O.’s role in company affairs up to the time of his departure for Lagonda is the author’s attempt, successful up to a point, to get inside the principal actors and explore their feelings and motives. Up to a point, because the creative W.O. was put on ice, protestations to the contrary notwithstanding. This Part’s thesis, if we grasp it rightly, is that [after Rolls-Royce acquired Bentley Motor in 1931] W.O. at best was never more than a development engineer and ought to have been happy to end up lapping the Continent in a Rolls-Royce bearing his name, all expenses paid. W.O.’s riposte to this stands for all time—the V12 Lagonda. And (on behalf of the other Bentley boys) it might also be murmured that the conclusion that Rolls-Royce was not totally beastly does not exactly spring from the pages of Elizabeth Nagle’s tales—item 4 in the Bibliography. But it all happened long and long ago; the dramatis personae continue, through Derby and Crewe days up to the present Chief Engineer, who happens to be the best technical committee chairman this reviewer has ever served under.

Part II. The Idealists, draws heavily upon company records now either in the possession of Rolls-Royce or else to be found in the Public Records Office. The author’s interpretive role continues, for which the reader is grateful; comprehension would indeed be difficult without it. As the tale moves forward into Rolls-Royce’s own bankruptcy, it is revealed that at one point and briefly, for corporate reasons, Bentley Motors owned the whole of the car-making part of Rolls-Royce. Well!

With Part III the story looks at motor racing; reader beware, all of the Parts are concurrent—but the overall view is the clearer for it. Now the book begins to introduce, increasingly, press clippings of the period as well as many of the Old Company’s charming publications celebrating a race won or a record taken. They are presented on a greatly reduced scale, making the use of a magnifying glass inescapable.

Part IV, and we arrive at The Motor Cars, enhanced by many more of the brochures, leaflets, catalogs, and general Bentliana produced by all of the companies. The original Gordon Crosby design for a mascot depicting, the author says, a winged figure of Icarus, is shown decorating a 3 Litre catalog. We had never realized before that Icarus was a girl. Color plates and black-and-white now continue in profusion; indeed, the second half of the book is largely pictorial. On the subject of the cars themselves, there is a lot of strange nonsense on pages 194 and 195 seeking to equate W.O.’s well-known disinclination to acclaim either the Blower 4½ (with a capital B, please), or the 4 Litre, to present-day attitudes of the Bentley Drivers Club (no apostrophe, please); a dated bibliography should not be permitted to prolong an outdated mystique. And the RC cars of the mid-thirties were the best of the bunch—so much for mystique! The author describes the enthusiasm at Crewe for a new Bentley in the spirit of the R Type Continental, and then tempers this with an explanation of the tremendous obstacles that must be overcome in engineering it.

And incidentally, this Part confirms the belief of the radical minority that has always held that every postwar pressed-steel Rolls is actually a Bentley with a flat hot water bottle on the front; even the Silver Spirit prototypes had Mulsanne radiators. There are a few errors or near misses, and one serious clanger: the Table in Appendix 4 describing the colors of the vintage radiator badges is all wrong. Chassagne’s name is doggedly misspelled until the Index. The well-known Embiricos streamlined car referred to in mysterious terms on page 40 was the property of Andre M. (whose cousin, Nicholas H. drove it on occasion), a fact confirmed in his letter to Stan Sedgwick, and to this reviewer by the son of Pourtout the coachbuilder during a visit to his works at Reuil-Malmaison. On page 126, contrary to the implication, the Barnato-Hassan racecar was built in Belgrave Mews West, and the Pacey-Hassan in an orchard in Wembley; both were housed at Brooklands during the season. There is a slight confusion on page 206 between the Mark V and the Corniche; none of the Corniche versions of the Mark V were completed, and the sole example known by that name was not a Mark V but experimental chassis 14.B.V. It appears in both pictures on pages 234 and 235, contrary to the caption on p. 233. Walter Sleator’s name is misspelled on p. 232, and Roney Messervy’s on p. 280.

Appedix 3 does not include the Birkin/Paget Blower cars, presumably on the narrow grounds that this is a book about Bentley Motors. In this same appendix, MT 2464 on p. 293 contains a “typo” avoided on p. 292. In Appendix 5 on p. 296, Mark 5 production was exactly 11 completed cars; this figure does not included experimental cars usng various Mark V components.

The book concludes with an attractive fold-out quick reference guide of outline drawings, covering all models from 3 Litre through Mulsanne.

To sum up: a superb book, excellently produced, film-set although you wouldn’t know it. Probably a book that Michael Frostick found required great care in the writing, if it were to achieve what he hoped for it. His hopes have been realized in giving us the only complete book of the marque and one of the most authoritative on W.O. Bentley.

Copyright 2015, Hugh Young (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter