Mercer Magic

Roeblings, Kusers, The Mercer Automobile Company and America’s First Sports Car

by Clifford W. Zink

I thought I knew about Mercer cars (1909–25). I’d seen the bright yellow Mercer Raceabouts at car shows, heard them run, knew they were a collector item, and assumed the history of the car company was much like a hundred others. Probably a Mr. Mercer had named the car after himself, like Winton, Pope, Duryea, Haynes, Lambert, Apperson and dozens of other initially successful car company founders who faded from the automobile manufacturing scene during economic panics, or downturns, as they are more gently described today.

Well, I was wrong. I didn’t know anything, but thanks to this very good book, I now do. The cars were fast, solid, well balanced, and powerful with a relatively small for its day indestructible engine. Mercer Raceabouts were a 1910 American version of what Bugatti became in Europe. Drive the car to the track, win easily, then leisurely drive home in the same car for a bit of tennis at the club or cigars at the bar. And like Bugatti, Mercer made a few hundred hand-crafted cars per year of all types that young wealthy people with a sense of sportiness and style wanted to own.

The wealthy and socially connected east coast Roebling and Kuser families owned the company. The cars were made to order under the type of supervision demanded by the very successful Roebling company, famous for building the Brooklyn Bridge, along with many other cutting edge technically advanced projects of the day. Intelligent engineering and metallurgy, when combined with conservative manufacturing and business practices, made the company immediately profitable.

Making money was not the reason the owners of the company built Mercer cars. They already had money. They wanted to have fun making cars that won races, and could be sold to the public in small volumes to offset racing costs by using the basic engine and driveline used in the high-performance Mercer Raceabout and Runabout throughout the product line. Mercer designer Finley Porter summed it up succinctly and simply when he said, “We sold race cars to the public.” Because of sound business habits, the company did make a steady profit, but expansion of the manufacturing base to compete in the mass market was never given serious consideration. Mercer cars were designed to compete on the track, not in the marketplace.

Mercer did eventually fail financially in 1925, but only after the original founders died and the company’s ownership changed hands. Under the new owners Mercer became part of a financially leveraged automotive empire organized for luxury sales. A panic temporarily killed the luxury market, and the empire dissolved, unable financially to wait for the bad economic phase to pass. Technical advances by other manufacturers also played a role in Mercer’s demise. Factory sponsored racing had been dropped in 1919 because the cars had stopped winning as easily as they had in 1911, and the few attempts to competitively update the cars failed at the track. Duesenberg and others had moved the art of engine building and drivetrain design to new technical levels, replacing Mercer in the public’s eye as the hot car to own.

In a sidebar, a dapper-looking William Barnes, a wealthy young Mercer race car driver and evidently a bit of a bon vivant, said “Racing drivers are the admiration of the younger people of the towns in which the races are held and everything is done to make their stay a pleasant one.” A photo shows him with his arm around a coy-looking young woman standing with him next to his racecar, apparently helping to make his stay in her town a pleasant one.

When examined closely, several of the finely detailed photos of drivers sitting in their cars just prior to the start of a race show a grimmer reality. Their faces reflect the strain and concern of dying during the event. The reality in 1911 was that a racecar driver’s life was not going to be a long one. It was not only the fans who were thrilled by the specter of death, but the drivers as well. To again quote Barnes, “there is that fascination about it that keeps old drivers from quitting, and tempts the younger blood to strive for a chance to flirt with death.”

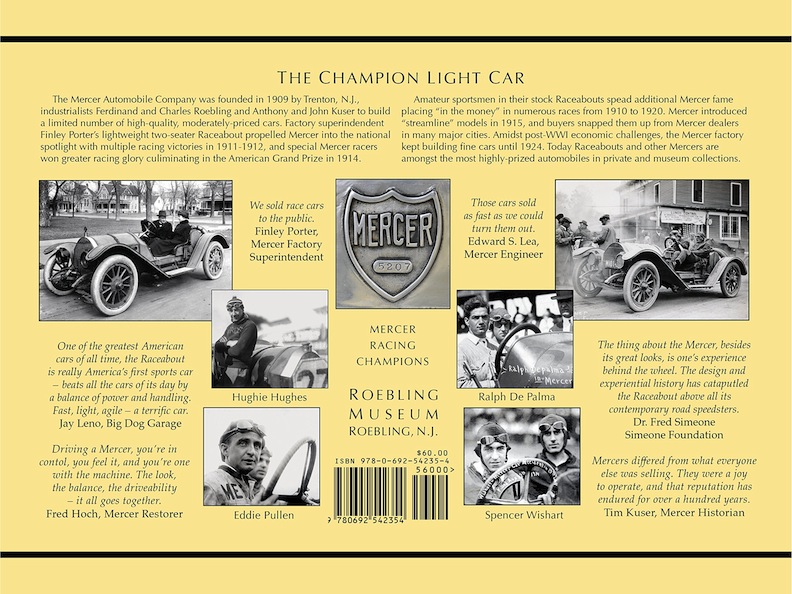

Mercer Magic is a large-format bright yellow hardback of 208 pages. It has no dust jacket and instead the front cover is imprinted with pictures of the cars and founders of the company, and the back cover with b/w historical photos of Finley Porter who designed the cars, and four of the factory race car drivers, including Ralph De Palma, pictured the same year that Mercer shocked the public by finishing second at the 1913 Indianapolis 500 Mile International Sweepstakes race against cars with twice the Mercer’s engine size.

Inside, the book opens with full-page illustrations of both the Mercer Raceabout and Runabout, taken from a 1912 catalog. A nice photo hand-colored in period-correct tints of a yellow Raceabout graces the title page, followed by a dynamic Peter Helck painting of Hughie Hughes winning the Savannah Challenge Trophy Race in 1912, followed on the next page with a beautifully clear period photo of Hughes powering through a turn at the Point Breeze Race Track in 1911 despite an obviously blown right rear tire. This visceral imagery sets the tone and the pace of the book, which remains consistent throughout.

An introduction by Tim Kuser, direct descendant of one of the founding families and Mercer expert, succinctly sums up what made Mercers fun to drive. “Like a thoroughbred horse, these cars liked to run, and for an owner who liked to drive fast, this was the car to own. With their power, accurate steering, conveniently placed controls and low center of gravity, they could be driven fast where others couldn’t.”

Acknowledgments and an Introduction lead off the first of twelve chapters devoted to a chronological retelling of the history of Mercer from beginning to end amply illustrated by 252 photos, 82 ads, catalogs, drawings, maps, stock certificates, cartoons, and four full-color paintings. The spaces around the illustrations are filled with informative text that flows through the book like a river of knowledge. The author combines action, adventure, money and reality to make the book come alive. It’s fun for me when I can get the feel of the time period, and this book delivers satisfaction on that and multiple other levels, including a sense of historical accuracy. The culture, humor and flirtations of youth are mixed with business structure, racecar preparations, designer squabbles, and all the rest that made Mercer the unique company it was.

Charts of Mercer race and road cars, the racing record, and an extensive Bibliography end the book. What’s missing is an Index, which really is an essential tool for the serious reader. For the technically minded—and what reader of a book about this type of car isn’t—a cutaway drawing of the car showing engine, drivetrain, and suspension would also be enlightening. A modern dyno test of horsepower and engine torque throughout the rpm range would help explain what such a car felt like to drive, as would data about center of gravity and roll center etc. But, such extras might easily turn a $60 book into a $90 book—that fewer people would buy. Compromises . . .

The design and layout of the book was done by Princeton Landmark Publications in Princeton, New Jersey, on the behalf of the Roebling Museum. Bill and Maeryn Roebling paid for the production, while the copyright is held by the book’s author

In closing, and so as to leave no loose ends: the cars were not named after an individual but Mercer County, New Jersey, where they were made.

A good book, well worth owning, but with some room for improvement.

Copyright 2016, Bill Ingalls (SpeedReaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

Would like to obtain the book , Mercer Magic , please advise. Is it available at Roebling Museum,Flanders?

Ed–we have nothing to do with sales!!