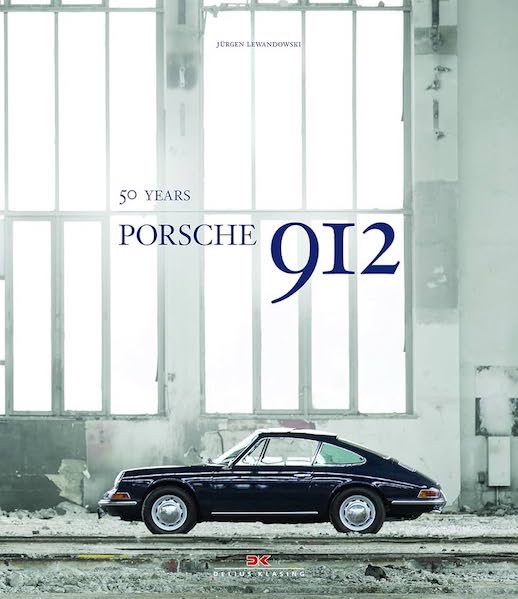

Porsche 912, 50 Years

by Jürgen Lewandowski

by Jürgen Lewandowski

“For many years, the type 912 was considered the stepchild of Porsche history. The interior was too spartan, the four-cylinder boxer engine too starved of performance—or so runs the opinion of some Porsche connoisseurs. Here I would like to disagree.”

—Wolfgang Porsche

The title could have used one more word: “50 Years since,” as opposed to of because the 912 was only produced for a short time—wherein lie the roots for it being often misunderstood.

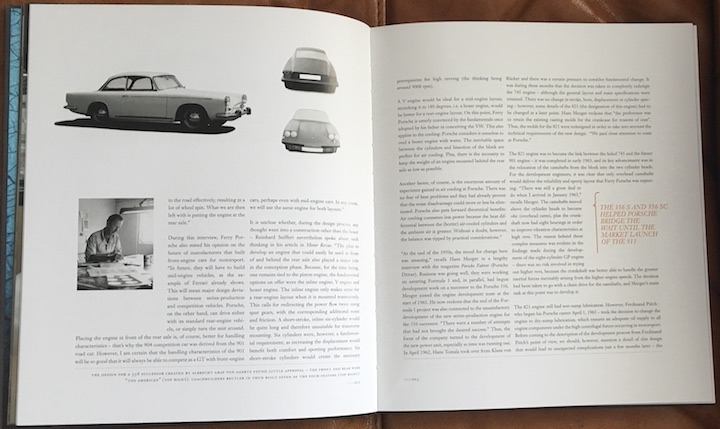

Some people—probably most—couldn’t tell a 912 from a 911 if they tried, most of the differences being in the cabin and under the hood. In simple terms, and befitting its role as an interim model, a 912 consists of the motor of the model it replaced, the then 17-year-old 356, and the basic body style and chassis of the car for which it was paving the way, the 911. Also, the 356 and the 911 were far apart in performance and technology—and therefore price—and so the 912 helped the buying public get used to the higher-priced Porsches that would become the company’s mainstay. That price differential is evident even today: while a rising tide lifts all boats, 912s never did see the drastic auction price increases of 356s and 911s, especially 911 Turbos.

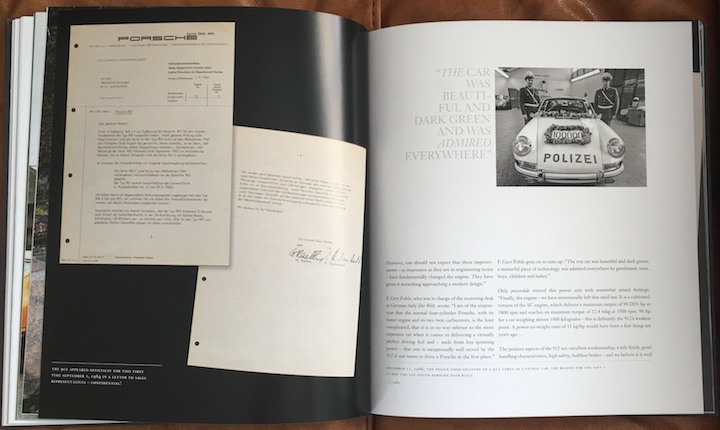

Built from 1965–69 (with a brief return appearance in the mid-1970s to help out another misunderstood Porsche, the 914) the 912 may have been only marginally more opulent than the 356 but its aerodynamic body gave it improved performance despite a nominally lower horsepower rating and increased weight. The public could clearly see that Porsche was taking its cars into an exciting direction and more than 32,000 copies found appreciative owners, including the German and Dutch highway patrol.

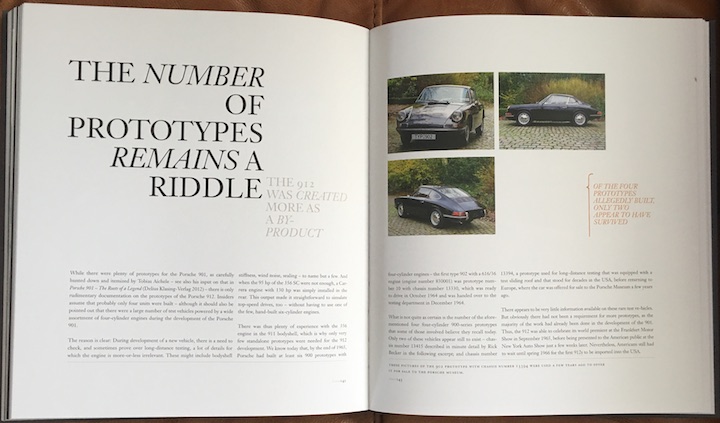

This book (also available in German) is a fully rounded account of the car, introducing into the record anew many details that had long been neglected or forgotten, showing the 912 as neither an afterthought (note, however, an important nuance: the author does refer to “the car that would save the company” as a “byproduct,” which is not the same thing) nor a stripped-down entry-level 911 but a properly thought-out model in its own right and a specific answer to a specific market demand.

To well-read Porsche enthusiasts a key nugget in this book will be the evaluation of a company directive that stipulated that “the type 901 [i.e. the 911] replaces only the Carrera series” whereas the 912 was targeted at what would have formerly been 356S and SC buyers. That the 912’s life cycle was to be relatively short has more to do with regulatory and image issues (cf. US emissions rules, competitive pressures and the “cylinder war”) and the struggles of a small manufacturer to effectively manage their limited resources than any inherent shortcomings of the car. The 912 crowd, in other words, will take this book as a long overdue validation.

To well-read Porsche enthusiasts a key nugget in this book will be the evaluation of a company directive that stipulated that “the type 901 [i.e. the 911] replaces only the Carrera series” whereas the 912 was targeted at what would have formerly been 356S and SC buyers. That the 912’s life cycle was to be relatively short has more to do with regulatory and image issues (cf. US emissions rules, competitive pressures and the “cylinder war”) and the struggles of a small manufacturer to effectively manage their limited resources than any inherent shortcomings of the car. The 912 crowd, in other words, will take this book as a long overdue validation.

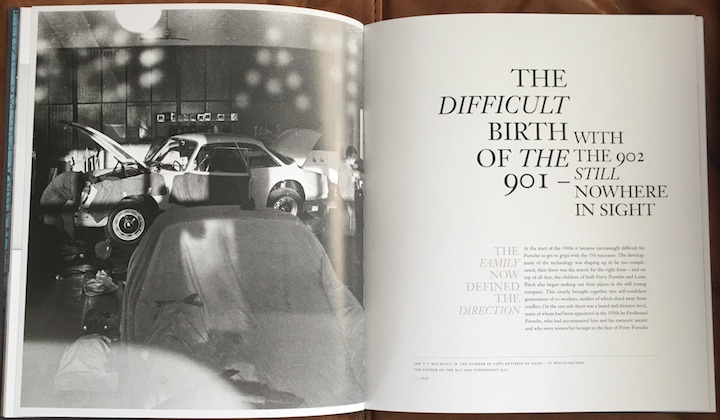

As Lewandowski’s 2010 book about the 901 whose story is of course totally connected to this one, this book fills an important gap in Porsche history. With some 90 books, innumerable articles, and several decades of automotive journalism under his belt, Lewandowski deftly operates on the macro level (such as the Porsche/VW relationship or the tug of war between engineers and accountants or even between Piëch and Kommenda) and the micro level (such as the murky subject of the genesis of the racing 912s).

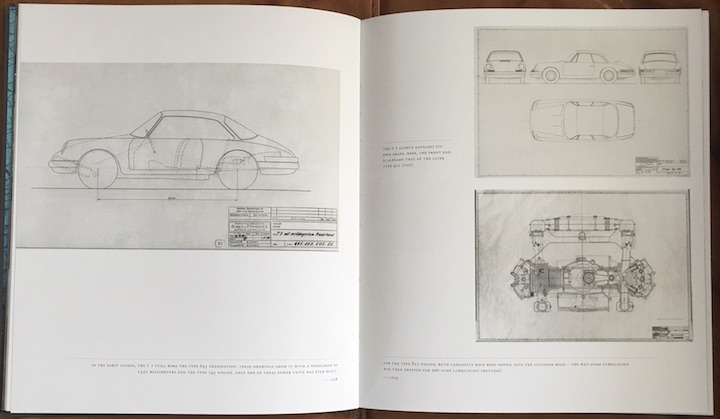

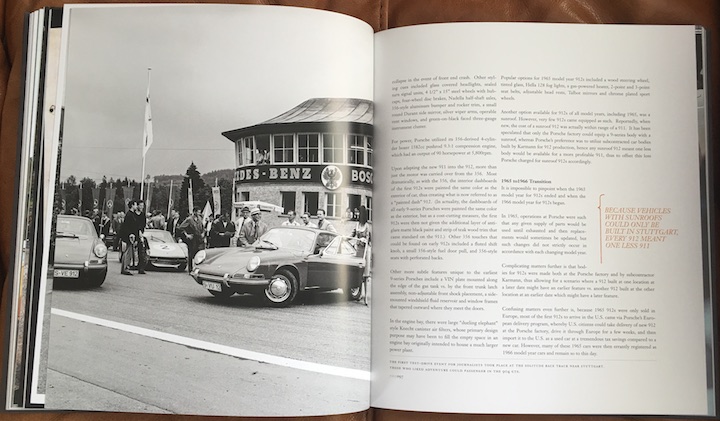

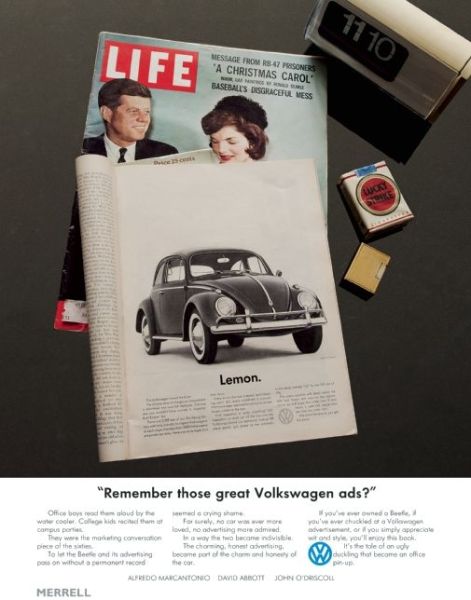

Those reviewers who praised the “large amount of technical information” on offer must have been reading a different book . . . there is minimal data, no tables or lists. Reference to performance stats is woven into the narrative. What the book does do, and very well, is to tell the story of the car’s design, development, and marketing. Reproduced are a large number of brochures, ads, and realia such as homologation papers for Group 1 racing.

One chapter is devoted to the accidental discovery in recent years of a close-to-production prototype in the US, now fully restored.

Copyright 2017, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter