Design Between the Lines

by Patrick le Quément, Stéphane Geffray

by Patrick le Quément, Stéphane Geffray

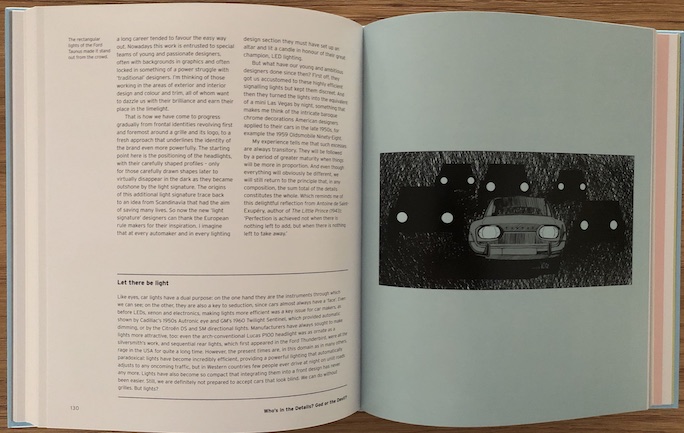

“Now what I am about to tell you will change the way you look at mass-produced objects, and you will become one of the initiates who may, just as an example, go on to scrutinize a smartphone screen with an educated eye. The secret is quite simple: any rectangle or square looks perfect when viewed square on. Yet if . . .”

Cliffhanger . . . we’ll stop the quote at the “if”—because that’s why you’ll want to read this book. The secret of the Mickey Mouse ears, “sculpted volume,” “continuity of transition”. And a hundred other things.

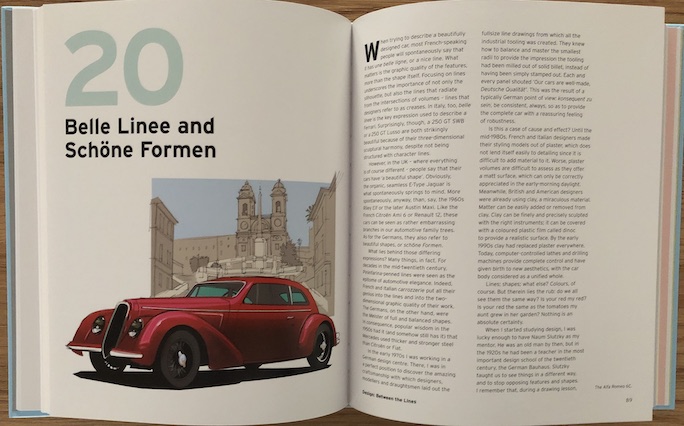

If you need more of a run-up to warm to this subject, consider this: at the time of the book’s writing it was already a good 15 years after the BMW 5 and 7 Series had introduced the edgy styling that polarized press and consumer alike (remember flame surfacing?) for years to come. The media and design professionals have meanwhile come to appreciate just how forward-thinking BMW chief designer Chris Bangle really was but to this day you’ll find Letters to the Editor (one example, right around the time this book was published: Motor Trend Dec. 2019) in which “car people” lampoon the “Bangle Butt” and the iDrive telematics interface (with which he actually had nothing to do). Meaning? Designers must be sensitive esthetes—AND have a thick skin. Bangle is of course discussed in this book, and in the best of contexts: being copied by his peers.

And with that we’re right in the thick of things. You’d have to have been sequestered on your private island for the last 50 years not to know the name of the author of this book. Simca, Ford, VW/Audi, and running Renault Design for over 20 years—some 60 million cars have Patrick le Quément’s fingerprints on them. Sure these cars are as mass-market as they come but that doesn’t make the design any less intelligent, original, or influential. Writer, critic, curator and design consultant Stephen Bayley, who has known le Quément since his early Renault days, calls him in his Foreword “perhaps the very most original designer working in the conservative car business at the turn of the millennium.” Both men are uncommonly articulate commentators on all manner of design and taste.

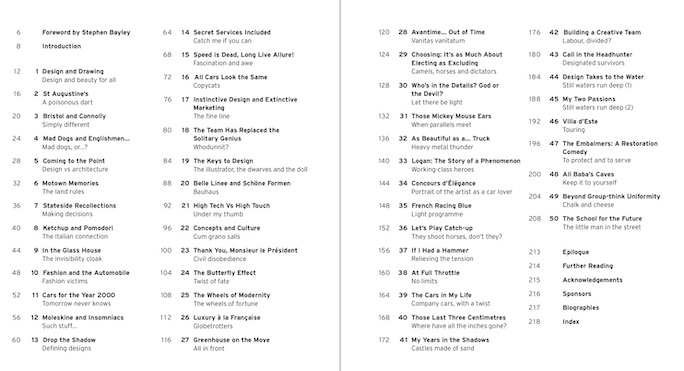

Now retired from the auto industry, le Quément (b. 1945) doesn’t offer this book as an autobiography but a highlight reel of 50 broad topics that interest him, each further augmented by sidebars penned by writer and scholar Stéphane Geffray. Car design is a common denominator but the book casts a wider net, touching upon cultural heritage, brands, and life in general.

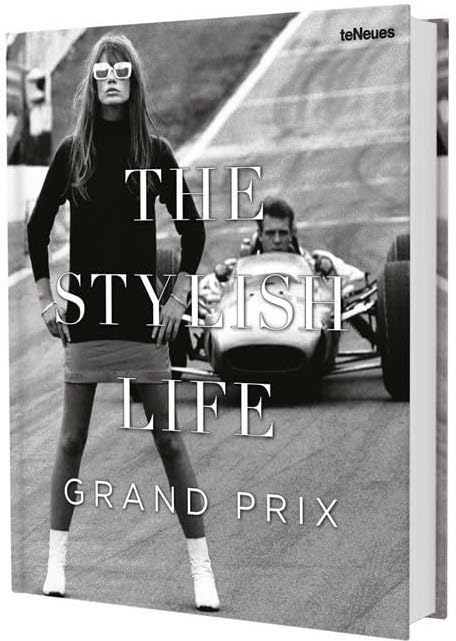

The philosophical and practical implications to a company or an industry of redefining the role of the in-house stylist (“an obscure activity whose members reported to Engineering,” and in the early years very much playing second fiddle to the creative sway held by outside, mostly Italian coachbuilders) to that of designer now treated as “a significant asset that could transform the destiny of a company” are complex and take the reader deep down the rabbit hole.

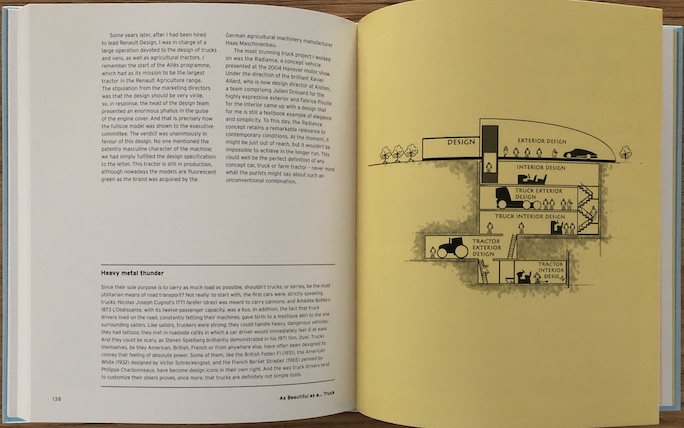

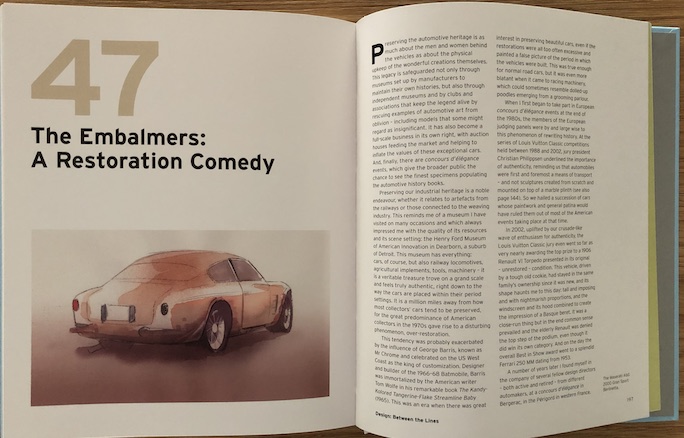

There is not a superfluous paragraph in this book, and the rich use of language is a joy to behold. That it is still rich in English (as le Quément’s name would suggest he is French) is thanks to Tony Lewin’s ministrations, not only a translator but a car/design/industry expert and author in his own right. All the lovely illustrations in the book are by Gernot Bracht, also someone who has worn/is wearing a multitude of hats in his professional life.

Also noteworthy is that the book has a Further Reading section and a fine Index. You do not have to be a design geek to find this book rewarding, but the mere fact that you are living means you actively, even if inattentively, engage with design, be it by man or by nature. So don’t be the know-it-all we wrote about in the opening paragraph—read this book and become one of the initiates instead!

Copyright 2024, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter