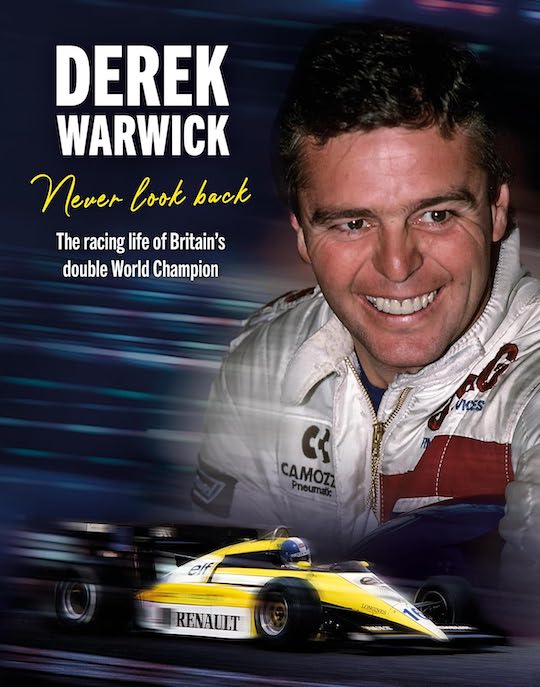

Derek Warwick: Never Look Back

The Racing Life of Britain’s Double Champion

by Derek Warwick with David Tremayne

by Derek Warwick with David Tremayne

“Was I a bad loser? Damned right I was.”

We’ve all met a Derek.

He’s the smart young guy at the family garage or the local tire shop, friendly, quick-witted, and so good at his job that you forgive him for flirting with your teenage daughter. Where I live, a Derek often has a well-used rally car or autograss racer parked at the back of the lot, or perhaps an old Formula Ford. Dereks sometimes win a race or two, but that frivolity stops when the mortgage and kids come along, and all that’s left are a few cheap trophies gathering dust.

But Derek Stanley Arthur Warwick (b. 1954) wasn’t like all the other Dereks, because he won his first world championship at 19 and his second nearly twenty years later. But the fact that his first victory was in Superstox and his second was in the World Sportscar Championship means that he never became a household name like Messrs Hunt, Hamilton, or Hawthorn. He had success in Formula One but, with his equally gifted contemporaries Martin Brundle and Mark Blundell, he never stood on the top step of a Grand Prix podium.

With help from David Tremayne, Derek Warwick has now written a 432-page autobiography—yup, it’s another doorstop of a book from Evro. Tremayne has almost thirty motorsport books to his credit, has been a long-time newspaper Grand Prix correspondent and, the last time I saw him, he was trying to break the British land speed record in his jet car. Ideally placed to co-author this book, in fact. It’s what might be called a deep dive into Warwick’s life with hardly a detail un-spared, nor race unrecorded, nor anecdote untold. There is the comprehensive account of Warwick’s life on track the reader expects, but that’s not all. We also learn about running Honda dealerships, property investment in Jersey, and (rather too much) about the silly japes race drivers get up to in rental cars and private aircraft. More intimately, we learn too about Warwick’s family life and about his recent encounter with cancer.

Warwick’s racing career is largely recounted season by season and, apart from his early days in stock cars, his career progression was the same taken by his racing peers in the Seventies. British Formula Ford 1600 and Formula Three and, where talent, luck and budget allowed, European Formula Two and then Formula One on the world stage. We are reminded how the past is a different country as, even in the Eighties, some journalists and commentators considered Warwick’s blue-collar background in stock cars rather “below stairs.” I certainly remember Warwick having an uncompromising style on track, but he mostly kept his act clean, unlike some of his competition from Brazil . . . It’s a delicious irony that the tough kid from rural Hampshire not only ended up being an FIA Driver Steward but also President of the British Racing Drivers’ Club, formerly the enclave of old buffers in brass-buttoned blazers.

The narrative is interspersed with short sections entitled “Other Voices” where family, friends, and colleagues add their own insight on Derek Warwick, both the man and the racer. This includes Arrows boss Jackie Oliver, United Autosports co-owner Richard Dean, and Les Thacker, the BP Motorsport Manager. It was the latter who gave Warwick his biggest break by funding a British F2 super team for the 1980 season. As Warwick puts it, “A Rory Byrne-designed Toleman F2 car, Brian Hart engine, Pirelli tyres, two British drivers—all under the banner of BP VF7 oil.” The account of that season, where Warwick’s tough guy team-mate Brian Henton beat Warwick to the championship, reveals a lot about the Warwick persona, and those insights are confirmed by the rest of his career. Commitment, honesty, and a ferocious work ethic are Warwick’s strengths—this is the guy who missed his sister’s wedding to race in F3 races in Germany and Spain. Tellingly, his wayward, life-and-soul-of-the-party, helicopter-flying and boozy Uncle Stan approved but dad Derry didn’t.

Tremayne enables the reader also to understand another aspect of Warwick’s personality. The man who made friends so easily also made more than a few enemies. The relationship with Brian Henton may now be healed but in 1980 he was the man about whom Warwick said, “. . . I never trusted Brian . . . I knew he would screw me over any time he could.” He makes no attempt to conceal his contempt for Teo Fabi for his weakness in the F1 drivers’ strike, he despised Peter Warr for reneging on Derek’s Lotus contract, and he despised Footwork technical director Alan Jenkins. And in modern parlance I guess we could term Derek Warwick and Eddie Cheever as the best of frenemies.

Derek’s Formula One career doesn’t belong in the woulda, shoulda, coulda dustbin of many peers, but he hoped—damn it, we all hoped—for better. Denied a Lotus drive by the Machiavellian Senna, he made his F1 debut to begin with the initially hopeless Toleman. He then got into the habit of joining the right teams (Renault and Brabham) at the wrong time before giving Arrows the best results its budget would allow and he signed off with a Footwork which was as bad as its silly name suggested. But that’s only half the story. If we judged a driver’s career solely by F1 wins, that would mean Pastor Maldonado was a better driver than Chris Amon. And that would never do. If you were at Brands Hatch in 1982, as I was, and watched Warwick muscle the Toleman TG 181C past Pironi’s Ferrari for second, there was no doubt about his commitment. There’s a few hundred families in Ushuaia who didn’t get the joke about calling the Toleman the Belgrano but even allowing for the under-fuelling, the working-class hero Toleman shouldn’t have been able to mix it with Maranello aristocracy. That July day was almost a metaphor for Warwick’s whole career.

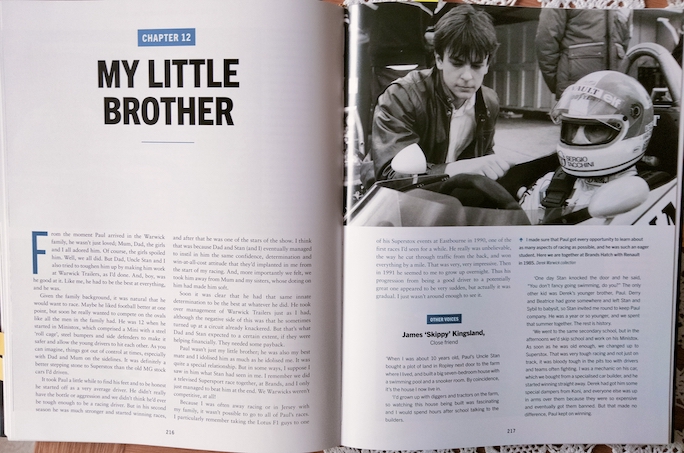

Warwick was no stranger to the dangers of racing and who better than David Tremayne to help him tell the story? Because it was Tremayne who wrote the only two motorsport books that have reduced me to tears: The Lost Generation (on the deaths of Tony Brise, Tom Pryce, and Roger Williamson) and Jim Clark – The Best of the Best. Warwick was first on the scene when Gilles Villeneuve died at Zolder: “It was the first time I’d experienced anything so violent and so close up.” Eight years later he saw his Lotus team-mate Martin Donnelly almost die at Jerez, and even worse was to come on July 21, 1991 when Derek’s kid brother Paul died in an F3000 race at Oulton Park. The chapter entitled “My Little Brother” must have been agonizing to write but tough read though it is, it is the strongest chapter in the book and I defy any reader not to be profoundly moved by a story told straight from the heart.

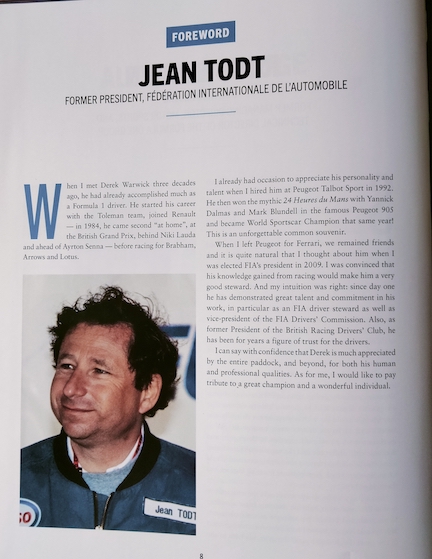

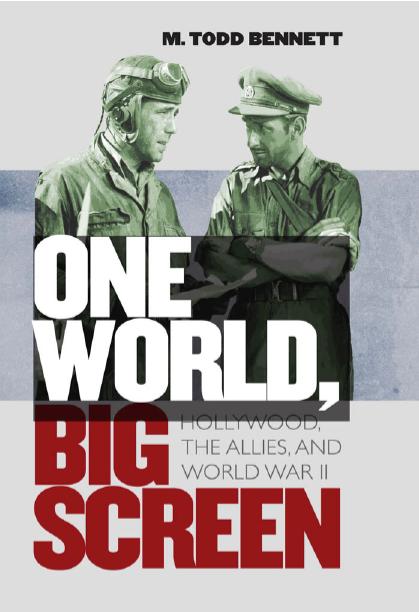

Forewords by Jean Todt (above), Ross Brawn, and Alex Hawkridge.

But racers race, and the grieving Warwick, against the wishes of most of his family (except most notably his mother) went racing again. Warwick recounts how he coped as he drove the TWR Jaguar XJR-14: “I put him [Paul] so far back in my mind that I almost forgot what he looked like.” Unlike his Formula One days, Warwick was in the right place at the right time for his sports car career, with a Le Mans victory and world championship in 1992. He carried on racing—GP Masters, Touring Cars—until signing off with a one-off celebrity Porsche drive in 2007, at Silverstone.

This is a well told, superbly illustrated story of the man who wasn’t just any old Derek, but the Derek who eventually left the family trailer business behind, raced with the best and beat them often enough to merit a book like this one. I suspect Derek isn’t troubled much with inner dialog, angst, and doubt—he’s no Damon (or Phil) Hill—because his strengths are self-belief, unbreakable confidence and sheer, bloody-minded commitment. And writing from the perspective of this reviewer, that really is a compliment.

Copyright John Aston, 2024 (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

I thoroughly enjoyed the parts of this book where Derek was totally honest – and informative – about his motor racing activities. He worked incredibly hard for what he achieved – and is a member of that (fairly exclusive) club of drivers who really should have won a F1 GP.

And as someone who had emergency hospital surgery just as Covid was kicking off, I totally empathised with Derek and his own health issues – brilliantly conveyed.

I confess that the book started to grate towards the end. Lots of ‘japes’ trashing hire cars, ‘hilarious’ link-ups with his best mates and an interminable list of favourable quotes from family and friends. He is quite rightly very proud of how he worked his way through the property chain on Jersey but again this took the focus off his sporting achievements.

This is not meant to detract from what he has achieved – both inside and outside motor sport. Not a bad read but (in my opinion) not as good as recent books on/by Geoff Lees, Jim Crawford, Gerry Birrell, Ian Flux and Bob Evans.