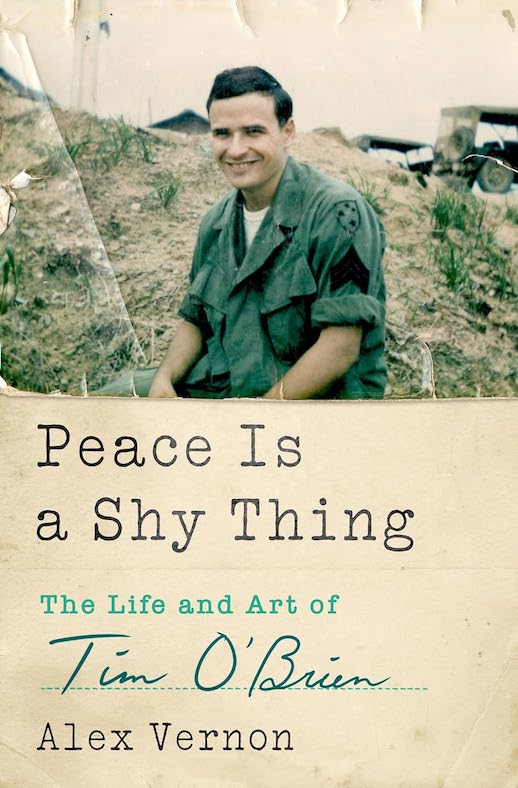

Peace Is a Shy Thing: The Life and Art of Tim O’Brien

by Alex Vernon

by Alex Vernon

Warfare can be discussed in the abstract. But how does that move the needle? This review begins with an autobiographical note because the book is a biography, and there is overlap.

***

After I returned from my tour in Viet-Nam, hung up my uniform (even if only rather briefly), finally finished my undergraduate degree and then moved on to graduate school, I found myself still—or again—grappling with the very war I had just been a part of.

Even before I was drafted during the summer of 1968, I had probably read more than most about the war already. Afterwards I found myself maybe not exactly obsessed with the subject but definitely absorbed by it, in both my academic studies and my personal time. My senior thesis was a paper dealing with pacification programs such the Strategic Hamlet effort, as an example. I read not only books by the likes of Bernard Fall, Malcolm Brown, David Halberstam and other journalists, but personal narratives by those who had served in the war, including the French forces in the earlier phase of the war.

While my readings shifted as I progressed in my graduate studies, I continued to seek out books that focused on the war from the perspective of the grunt that I myself had been. Nonfiction—novels—came closest to my lived experience. One of the first papers I wrote in grad school concerned basic training and infantry AIT (Advanced Individual Training) in the Army. It considered whether the training that soldiers received prior to being assigned as replacements for infantry units serving in the field had been adequate. I also looked at the training soldiers received after being assigned to a serving division, which consisted of usually a week or so of classes before being sent to a line company in the field.

A later paper looked at the grunt’s experience from about the latter part of 1965, when the buildup was beginning, until just after the Cambodian excursion in mid-1970 when unit withdrawals really started to pick up. That one was more of an information paper for the seminar than the more scholarly sort of paper. One of the reasons I wrote it was because I had not experienced that sort of war in Viet-Nam. I was a member of a Lurp (Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol/ Long Range Patrol) company which then became a Ranger company in February 1969. I also spent considerable time with the PRU (Provincial Reconnaissance Unit) program. Only a few times when we did “stay-behind” missions with a line (leg) unit did I ever find myself in the field with more than six or eight people. In addition, we often worked with units from 5th Group of Special Forces and SEAL teams. In other words, while I might have been an 11B, Infantryman, the experience of being an 11B grunt wandering about the countryside in platoon or company formations was actually alien to me.

The Flying Fickle Finger of Fate nudged me in a direction I had never anticipated. I had certainly experienced far more combat than I would have if I had been assigned instead to a line unit as a grunt. As a Ranger team leader I had at least some semblance of control over my fate (or at least a reasonable delusion thereof): I could make decisions and I could, at least in large part, help determine the fate of my team as well as myself. At least, that is how I felt.

About the time I started grad school, I read, for the first time, Tim O’Brien’s If I Die In a Combat Zone, Box Me Up and Send Me Home (1973) It had been out for some months before I got around to reading it. To this day, I remember thinking: Thank goodness I was a Ranger and was spared this sort of thing! Reading O’Brien’s experience certainly influenced my choice of topics for the two grad papers I mentioned above.

Fast forward to the present: until fairly recently, I only had a rather general if not vague idea of the full scope of O’Brien’s Viet-Nam experience. He graduated from Macalester College in late May 1968 and was accepted into graduate school at Harvard University to start that fall. However, in the wake of the Tet Offensive earlier in 1968, student deferments for graduate school were dropped, meaning that O’Brien would no longer be exempt from The Draft. In June, he underwent the usual pre-induction physical examination, followed by his local Draft Board reclassifying him II-2, student, to I-A, eligible for military service. This led, inevitably, to his being inducted into the Army in mid-August 1968. O’Brien was assigned to Fort Lewis for Basic Training and AIT (Advanced Individual Training) as an 11B, Infantryman. In 1968, an MOS (Military Occupational Specialty) designation of 11B, Infantry, meant you had about a 100% chance of being sent to Viet-Nam.

O’Brien arrived in Viet-Nam in February 1969, spending the first part of his tour with Alpha Company, 5th Battalion, 46th Infantry, part of the 198th Light Infantry Brigade, one of the units comprising the Americal Division (the 23rd Infantry Division) the other two brigades being the 11th and the 196th. The division was headquartered in Chu Lai, Quang Ngai province. He served as the company RTO for the first part of the tour and then in the battalion’s S-1 shop at LZ Gator as a clerk for the last part of his tour. He extended his tour to 13 months so as to take advantage of the “Early Out” program then in place for those returning from Viet-Nam with only a few months of active duty remaining. Doing so allowed O’Brien to avoid being assigned to a stateside unit for just a matter of months, meaning he would be able to get on with life months earlier than otherwise possible.

That O’Brien spent much of his time in and around “Pinkville” and My Lai 4—the scene of the infamous 1968 war crimes—obviously informs his writing. Along with his regrets about “allowing” himself to be drafted in the first place—O’Brien had seriously considered evading the draft by going to Canada and later by deserting during his time at Fort Lewis.

If I Die In a Combat Zone, Box Me Up and Send Me Home (1973)

Going After Cacciato (1978)

The Things They Carried (1990)

These are just three of the books that Tim O’Brien has written over the past half-century. All three relate to the 13 months he spent in Viet-Nam serving with the Americal Division.

Going After Cacciato earned the National Book Award in 1979. By coincidence, Going After Cacciato and the movie The Deer Hunter both appeared the same year, both considering the American experience in Viet-Nam and both raising questions regarding the war. And both earned awards, with the Academy Award for Best Motion Picture going to Michael Camino’s film. Then, when O’Brien received the National Book Award in 1979, Apocalypse Now was released.

Since its publication in 1990, O’Brien’s The Things They Carried has become a “staple of high school and higher education classrooms, appearing on more college and university reading lists globally than any other U.S. novel or any other modern novel.” Scarcely a surprise to me, but still kind of amazing. And it means that some of you folks must have encountered O’Brien’s work along the way, meaning you’d want to know about this biography, Peace Is a Shy Thing: The Life and Art of Tim O’Brien. At over 500 pages long, this book has “shelf presence.” It may even look too big to want to pick up! Alex Vernon has done extensive and comprehensive research into both O’Brien The Soldier and O’Brien The Writer. Exhaustive would be the word. At times it feels as if the research is leading the narrative, not the analysis and interpretation. Vernon is a West Point graduate—the only literature major in his class of over a thousand—but saw active duty himself in the Persian Gulf War.

I sliced through the book as a work of both biography and literary criticism. Vernon does demonstrate the validity of historian Barbara Tuchman’s theorem regarding the seductive nature of research and the difficulty and hard work of turning that research into prose. As so many of us (myself included), Vernon seems to have found it difficult to pare down. Even so, the end result is an effective and, yes, appropriate lens to consider O’Brien.

There is a sense of guilt O’Brien retains even decades after his Viet-Nam tour, and it permeates his writing. Vernon isn’t wrong when he says that O’Brien can be not only prickly at times but also a prick. As Vernon and O’Brien both make clear, the decision by O’Brien to submit to The Draft in the summer of 1968 was one that deeply troubled O’Brien at the time and also long after: you only need to read any of his stories to sense just how troubling that decision was.

Vernon relates that O’Brien was among approximately 90,200 men drafted into the Army and Marine Corps between July and December 1968. It occurred to me that had O’Brien not been drafted in 1968 but instead been deferred by graduate school, the Draft Lottery that began 1 December 1969 for men born between 1944 and 1950 would have, based on his birthdate (1 October 1946), spared him being dumped at LZ Gator with A/5-46IN in February 1969. He would have been #359.

Yes, this is a big book, but don’t let that stop you—O’Brien is one of the more important authors of recent years!

An Aside: O’Brien is only a few months older than I am, but I was drafted a month earlier, in July 1968. We both ended up classified 11B, Infantry, but I arrived in Viet-Nam two months earlier than he, in mid-December 1968, which put me into the Mekong Delta with the 9th Infantry Division. When they drew my number in the December 1969 Draft Lottery, O’Brien beat me: my number was 299. But I was only weeks away from ending my tour rather than several months like O’Brien . . .

Copyright 2025, Don Capps (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter