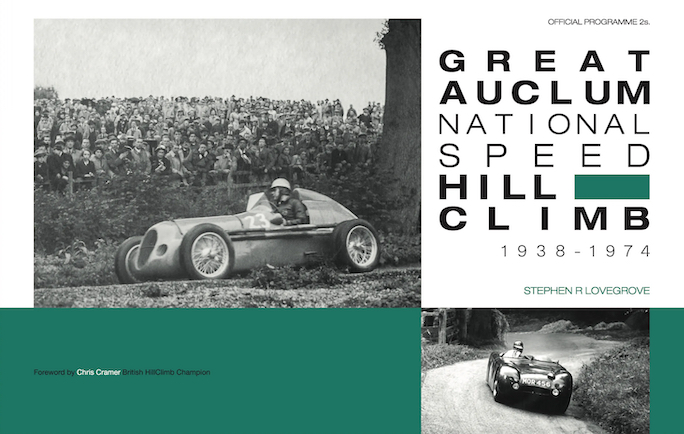

Great Auclum National Speed Hill Climb 1938–1974

by Stephen R. Lovegrove

“It is difficult to explain the excitement generated by racing coming to our sleepy little village, but nothing will ever match the thrill of those days. The memories burn bright—and loud!”

“Mum, the racing cars are back!”

Here’s a question for you. Do you think the Monaco Grand Prix is an anachronism which should have no place on the Formula One calendar? That Nelson Piquet was right when he said that driving at Monaco was like “riding a bicycle around your living room”? Or do you think that there’s much more to a Grand Prix than overtaking, and that qualifying at Monaco is the most thrilling hour in the Grand Prix season?

If you are in the latter camp (where you’ll find my flag already flying) you’ll love speed hill climbing. It’s one of the oldest forms of motorsport—Shelsley Walsh has been holding hill climbs since 1905—and it’s still hugely popular in Britain and Europe. American readers might usefully imagine British hill climbs as being the vodka shots of motorsport, short but hyper-intense, because no current British venue takes even a minute to ascend.

This lovely book is about the Great Auclum hillclimb, whose 440-yard course is just one fiftieth the length of the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb. And let’s not even bother with comparing altitude differences.

Located in Berkshire in the southeast of England, Great Auclum held an annual hill climb between 1936 and 1974, and this book is Stephen Lovegrove’s loving tribute to the venue. “Love” is the mot juste, as the author grew up literally a stone’s throw away from the course, attended his first event at the age of four and even avoided a family wedding in order not to miss his annual fix of racing cars.

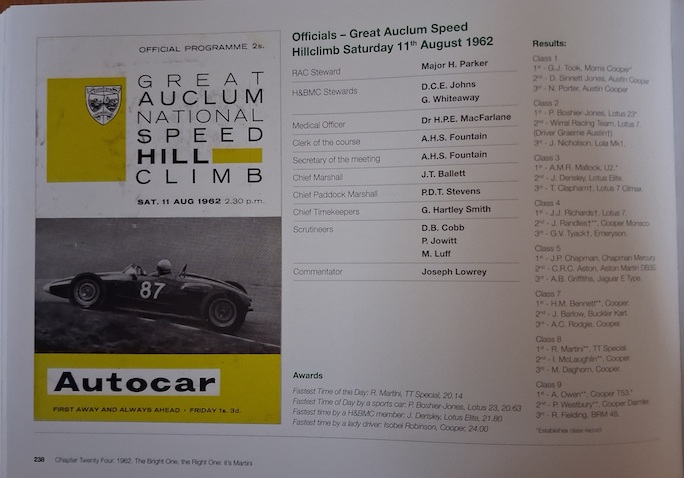

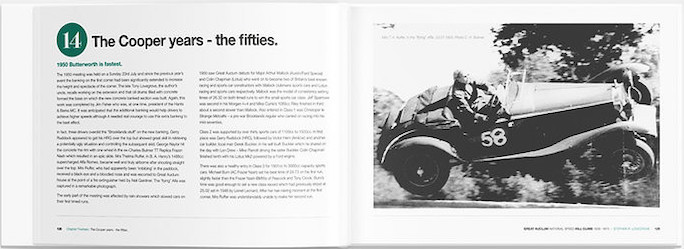

The book tells the full story of this endearingly quirky venue from its construction, just before the Second World War, to its closure in the 1970s. I haven’t double-checked (peccavi) but I think every single event held at Great Auclum is described. The text is interspersed with extracts from the results, copies of the programs, mini-biographies of the more notable contestants, as well as scores of period photographs. There’s a lot of material to digest in each of those categories, and to give an insight into the look and feel of the book I will comment on each of them.

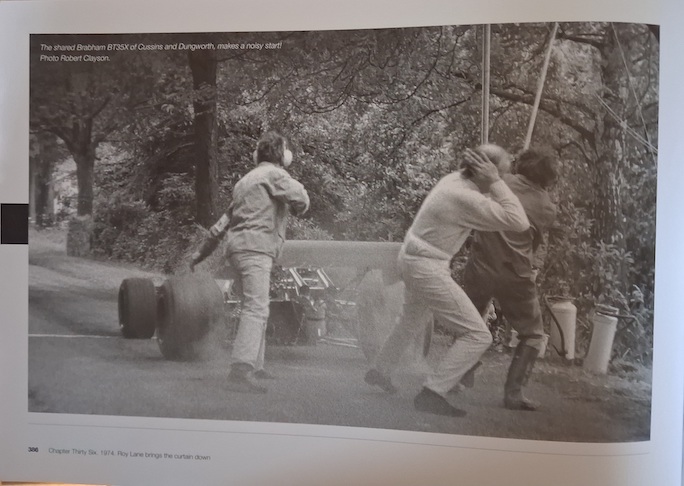

Why ear protection can be a good idea.

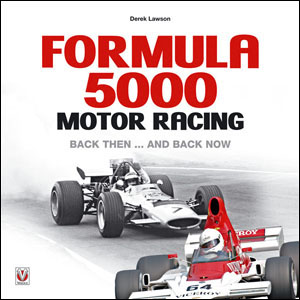

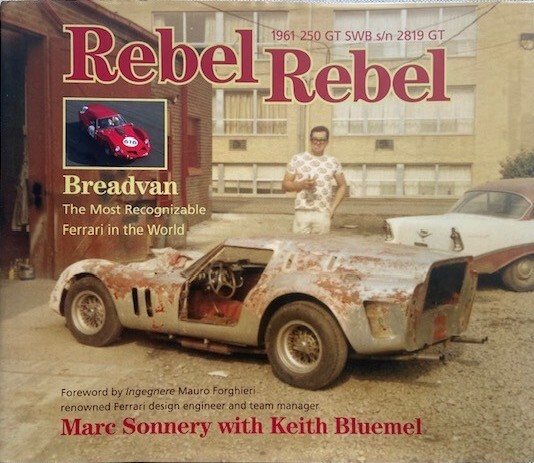

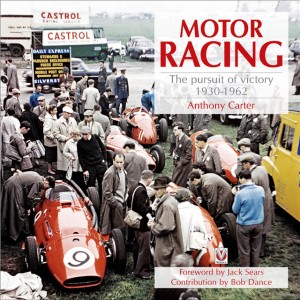

Results first, and it’s fascinating to contrast the prewar entries of Frazer Nashes, Alvises, and sundry MGs with the extraordinarily potent single-seaters that dominated speed hill climbs in the Sixties and Seventies. F5000 McLarens, Brabham and March F1 and F2 cars, and one-off hill climb specials like the formidable four-wheel drive Hepworth FF. I was a start-line marshal at hill climbs in the early Seventies—though not at this venue—and I confess I became misty-eyed at so many reminders of the cars that had entranced and nearly deafened me as a teenager. None more so, perhaps, than Jack Maurice’s Ferrari 250LM, whose owner would drive the whooping and snarling Berlinetta on the public highway to venues all over Britain. This car was last sold for $17m but if cars have souls, I bet the 250LM misses its salad days, when it was just another old race car enjoying its days in the sun at Great Auclum.

Program from August 1962.

There are several remarkable things about the event programs. Their style hardly changed in forty years, and even in 2026 a hill climb program has an almost identical format. How I love the sheer quirkiness of an event that always had a special class for gas turbine-powered cars, despite the fact that none was ever entered. And while last year’s Formula 1 cars are already museum pieces, many of the cars that competed in the early years of Great Auclum are still actively campaigned in Vintage Sports Car Club events. (As an aside, I’d recommend any American enthusiast on vacation in the UK to visit a VSCC event; it’s where Downton Abbey meets Brooklands. Big shot sponsors? Corporate guests and VIPs? Get outta here!)

The number of “names” who competed at Great Auclum might seem extraordinary to those unfamiliar with the status of the speed hill climb, especially in the late Forties and Fifties. How about Colin Chapman, John Cooper, Tony Crook, Alec Issigonis, Ken Miles (now beatified after the Le Mans ‘66 Ford v Ferrari movie), and even one Stirling Craufurd Moss? The author includes short biographies of many luminaries, from Frazer Nash 1937 record holder AFP Fane to Stuart Lewis-Evans (ftd* in 1953 in a Cooper Norton) and also many of the drivers with whom I once chatted as they waited to be called to the start line.

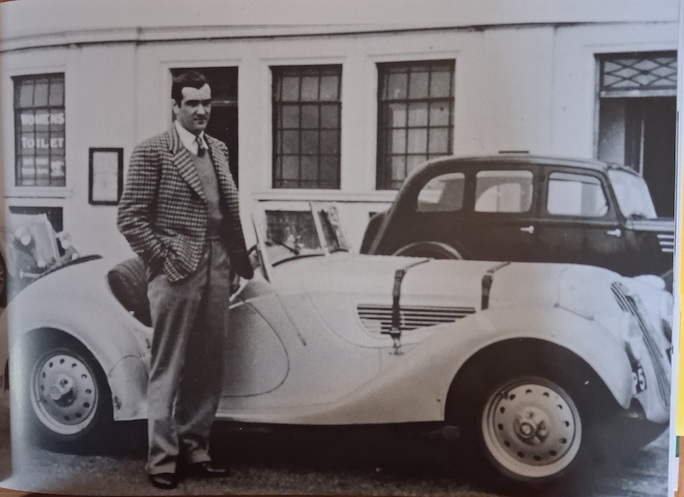

AFP Fane with his Frazer Nash BMW 328 in 1939.

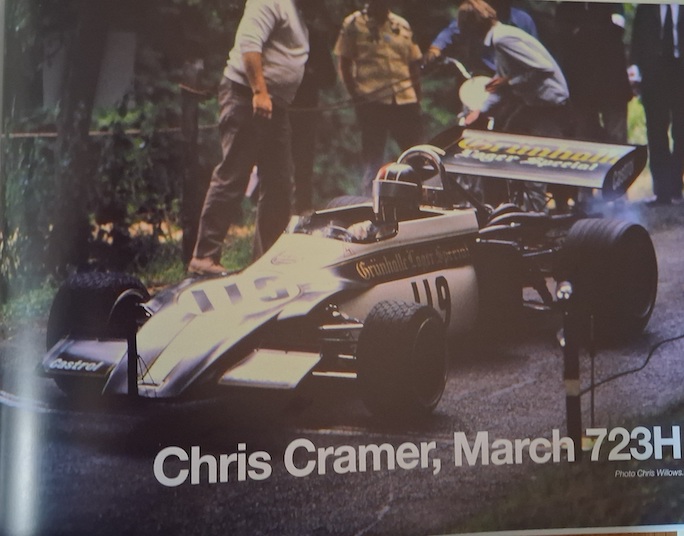

Men such as all-time course record holder (17.65 seconds!) Chris Cramer, yoghurt magnate David Good, engineer Roy Lane and the charming Sir Nicholas Williamson, officially the 11th Baronet Williamson—“Always reluctant to discuss his private life, when asked what he did for a living, he would famously reply ‘Not very much at all actually’”. Bertie Wooster made flesh. Eccentricity is part of hill climbing’s DNA.

The all-time record holder.

I once talked to the owner of a 1913 Theophile Schneider, powered by a 10L Hall-Scott aero engine at a vintage hill climb. He told me how he and his fearsome steed had just returned from a trip where they’d driven the route of the 1908 French Grand Prix, so I doubt Harewood’s 1585 yards had been much of a worry. I loved the author’s account of Thelma Ruffer’s antics at the 1950 event: “Mrs Ruffer, in BA Henry’s 1488cc supercharged Alfa Romeo, became well and truly airborne after shooting straight over the top [of the banked corner]. Mrs Ruffer, who had apparently been ‘imbibing’ in the paddock, received a black eye and bloodied nose and was escorted to Great Auclum house at the point of a fire extinguisher by Neil Gardiner**.”

Thelma Ruffer’s unpleasantness.

The photographs in this wonderful book add to its charm, not least because so many of the early shots are of such terrible quality. In 2026 we are spoiled by pin sharp digital pictures, where there is no limit to the number of images, and where errors can be edited out. But in those analog days of simple cameras with limited film, the results are often no more than vague and grainy impressions of the subject. But they are all the better for it, and testament to a technical zeitgeist which was light years distant from today’s hyper reality.

Reports of events before 1962 are culled from contemporary sourcesand their style reflects their era, such as this pearl from Autocar, on the 1939 hill climb: “Summing up, it was all very amusing for the competitors, in spite of the greyness of the skies.” But from 1962, when the author was present for the first time, a slightly more personal style of reportage appears, but I’d have liked even more personal recollections.

There’s no lack of detail, with class battles, winning times and retirements all being covered, leaving me to wonder if any detail was not included in this 414-page heavyweight of a book. A shame, though, that there’s no Index.

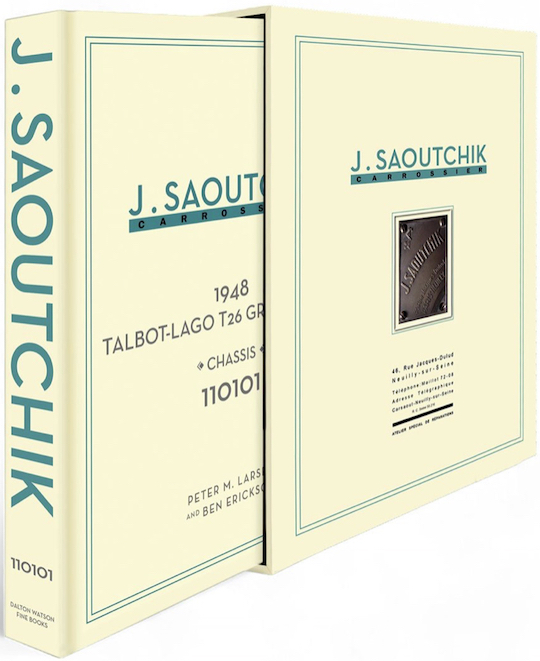

The book is beautifully designed and presented, as one might expect from the relatively high price. Limited to 200 copies of which 100 come in a slipcase and are accompanied by a certificate of authenticity signed by hill climbing royalty, including Chris Cramer, Peter Boshier-Jones, and David and Sean Gould.

The book is beautifully designed and presented, as one might expect from the relatively high price. Limited to 200 copies of which 100 come in a slipcase and are accompanied by a certificate of authenticity signed by hill climbing royalty, including Chris Cramer, Peter Boshier-Jones, and David and Sean Gould.

This is an enchanting book, and an essential purchase for students of British speed hill climbs. And even if that is not your specialty, I can think of few books that offer a better insight into the history of British amateur motorsport. It is a gem.

*ftd – fastest time of the day

**Neil Gardiner– racer and industrialist, the owner of Great Auclum House, and designer of the hill climb course

Copyright John Aston, 2026 (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter