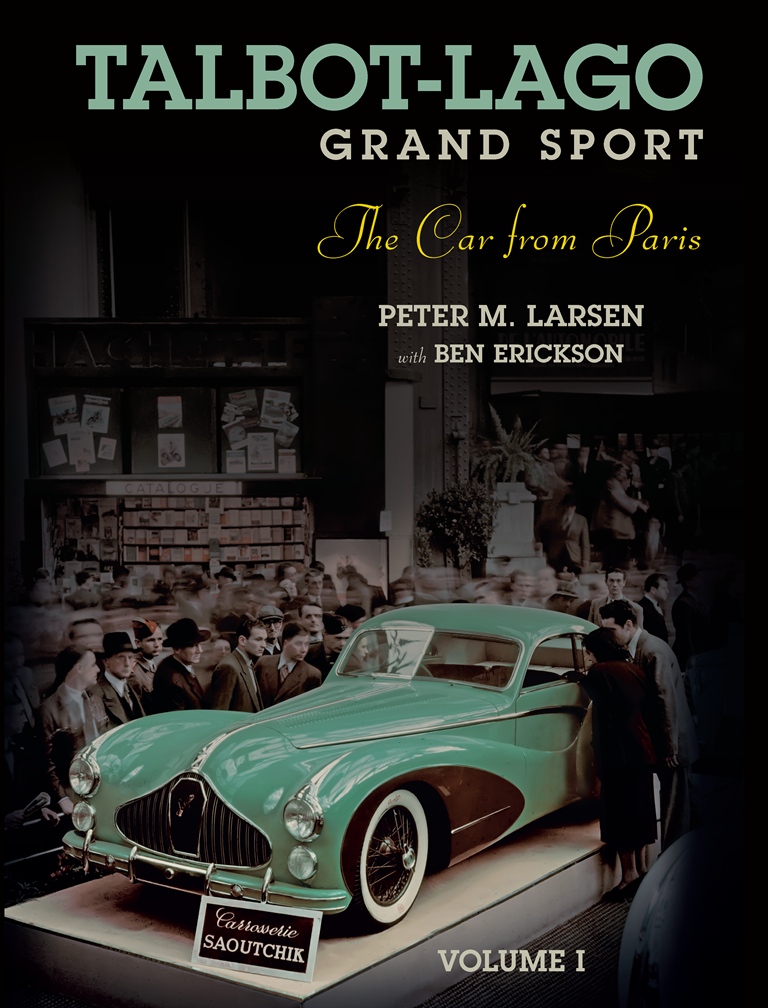

Talbot-Lago Grand Sport: The Car From Paris

by Peter M. Larsen & Ben Erickson

by Peter M. Larsen & Ben Erickson

Glass half full: one of the authors used to own a T26 Grand Sport L (#111013).

Glass half empty: he sold it in the 1990s because he didn’t know any better.

While the Longue version is not as valuable as a GS model it still came as a shock when just as the ink on this book was drying, a 1947 Talbot-Lago T-26 Grand Sport (#110113) fetched a record $2,035,000 at auction. Good thing Larsen has another one! And this one a GS! There weren’t many made—less than 40—and some people own more than one so there are not a lot to go around. Nor are there many books in this limited numbered edition to go around: 600, plus 100 in leather.

That record sale—irony of ironies—occurred at Barrett-Jackson, that powerhouse for American muscle cars that only two years ago rediscovered its roots in full classics. If this proves anything it is that there is no telling what will win favor or why. This new Talbot book, though, is a sure winner and we can tell you why.

It ought to suffice to say that this is a Dalton Watson book to give you confidence that it is important. It also means that it is the sort of specialized book that not many publishers would go near, and that it will be extraordinarily well put together. But even among the many upscale DW offerings, this newest opus scales new heights—not least in price, which absolutely pales in comparison to the sheer spectacle of handling this confection. Everything about is an event: from relieving the delivery person of a weight so tremendous s/he’ll want to put in for hazard pay to tearing into the box to find a plastic-handled cardboard carrying case containing a slipcase containing two books. Not something you see every day!

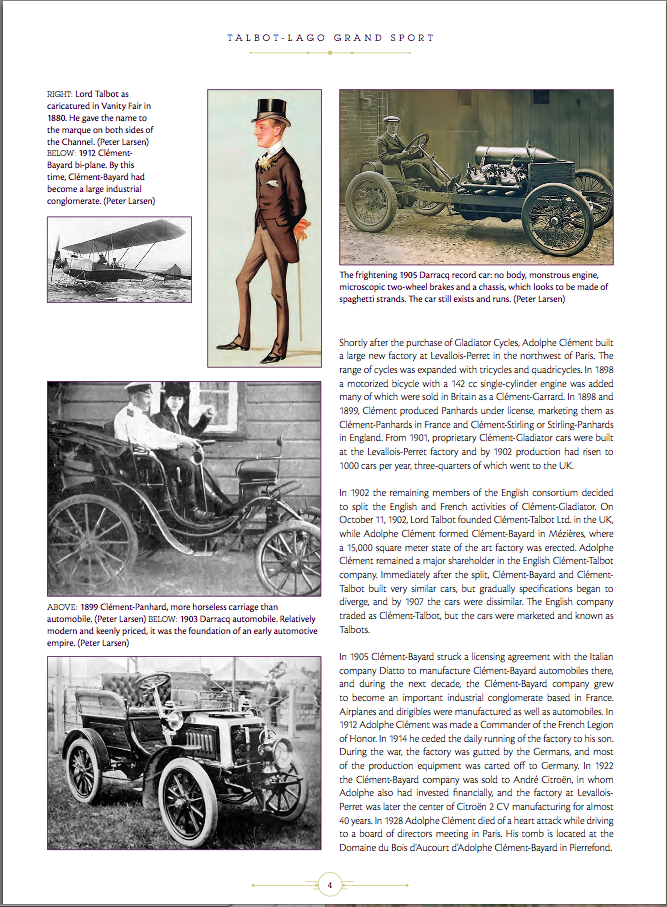

Even if you were to have no interest in Talbot-Lagos in general or the “sleeper” postwar models like the Grand Sport in particular, you’ll still want to know about this book because volume 1 is a really good soup-to-nuts primer on the political and economic currents of the era and the French coachbuilding scene. (Vol. 2 deals exclusively with each individual GS chassis.) It also introduces many strands from various corners of the Anglo-French automotive world that came together in the Sunbeam-Talbot-Darraq conglomerate whose history is even more convoluted than most of its peers’. It probably surprised one man from among the S.T.D. crowd as much as anybody that his name would be the one to become the second half of the company name, Italian-born (1893) and -trained engineer Antonio “Tony” Lago. To him is devoted a chapter here and even with this much room to roam, the authors struggle to pin down what made him tick. Picture young Lago walking through the doors in 1934, brimming with radical ideas and boundless enthusiasm for building some of the most expensive cars under the sun. Fast forward 10, 12 years: “It is indisputable that after the war, Lago went from being a dervish in business to an aging and obdurate man, incapable of recognizing change and reacting properly to it. This in itself is neither rare nor remarkable, but it is certainly sad.” And it is the backdrop to the Grand Sport era.

Even if you were to have no interest in Talbot-Lagos in general or the “sleeper” postwar models like the Grand Sport in particular, you’ll still want to know about this book because volume 1 is a really good soup-to-nuts primer on the political and economic currents of the era and the French coachbuilding scene. (Vol. 2 deals exclusively with each individual GS chassis.) It also introduces many strands from various corners of the Anglo-French automotive world that came together in the Sunbeam-Talbot-Darraq conglomerate whose history is even more convoluted than most of its peers’. It probably surprised one man from among the S.T.D. crowd as much as anybody that his name would be the one to become the second half of the company name, Italian-born (1893) and -trained engineer Antonio “Tony” Lago. To him is devoted a chapter here and even with this much room to roam, the authors struggle to pin down what made him tick. Picture young Lago walking through the doors in 1934, brimming with radical ideas and boundless enthusiasm for building some of the most expensive cars under the sun. Fast forward 10, 12 years: “It is indisputable that after the war, Lago went from being a dervish in business to an aging and obdurate man, incapable of recognizing change and reacting properly to it. This in itself is neither rare nor remarkable, but it is certainly sad.” And it is the backdrop to the Grand Sport era.

As an aside, if this quote struck you as well crafted, realize that both authors are not only car but also language guys, with academic backgrounds in literature and linguistics. While there surely was overlap, Larsen acted as lead writer and Erickson focused on research, photography, and digitization of archival material. (Painting word pictures is not an exact science: the aforementioned $2.3 mio Franay-bodied auction car is first described as “large and almost forbidding, but still svelte and swoopy” and later “looking almost like a charging rhinoceros.”)

As an aside, if this quote struck you as well crafted, realize that both authors are not only car but also language guys, with academic backgrounds in literature and linguistics. While there surely was overlap, Larsen acted as lead writer and Erickson focused on research, photography, and digitization of archival material. (Painting word pictures is not an exact science: the aforementioned $2.3 mio Franay-bodied auction car is first described as “large and almost forbidding, but still svelte and swoopy” and later “looking almost like a charging rhinoceros.”)

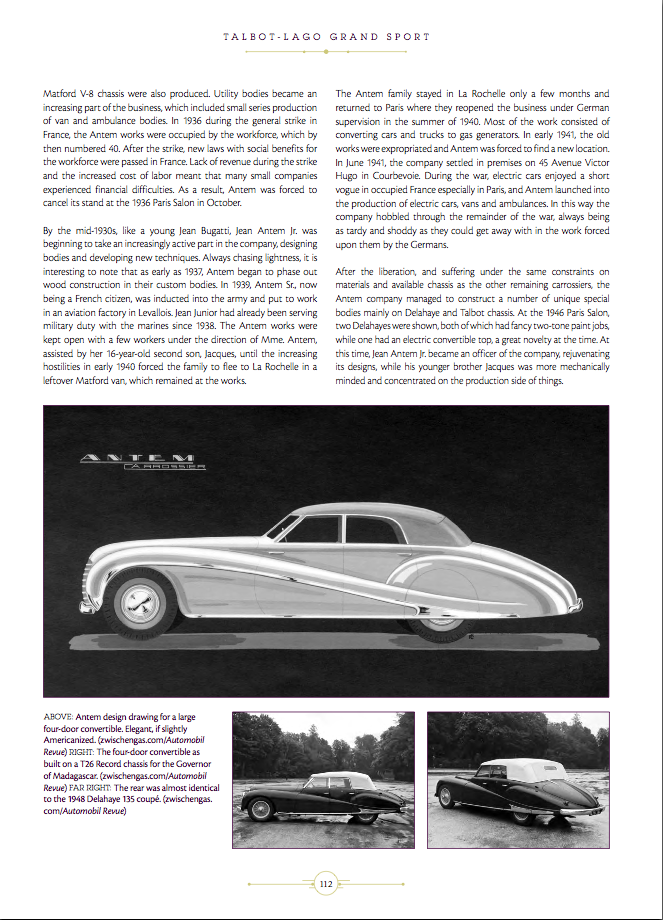

Assuming that knowledge of model and marque is not going to be widespread, volume 1 is used to properly set the scene and create context. It is, for instance, immensely useful that most everything the text mentions is also illustrated, especially other cars of the time without which the GS could not be properly appreciated. After explaining the industry and the key protagonists in the Talbot story, as well as the competition connection that was so integral to Lago’s positioning of the brand and also Lago’s earlier role in the development of the Wilson gearbox, the focus shifts to chassis design and construction, and then to the 18 coachbuilders that bodied or rebodied Grand Sports.

Thanks to a multitude of resources the illustrative and archival material is enormously wide-ranging and even the expert reader will surely make new discoveries here. Blueprints, technical diagrams, detail shots of components, promo material, and coachwork drawings are augmented with photos of restored cars.

Appended is a detailed list of all GS chassis (incl. original but not current owner), a discussion of mystery cars, pages from sales brochures, a reprint of an Autocar article, short commentary on the T26 Record model, and illustrated descriptions of GS scale models. The Bibliography is so detailed that it not only lists every book and magazine article by CIP data but also the specific chassis/subject covered—but what it doesn’t tell you is that it contains only those items the authors used in their work as opposed to everything ever published (even recent items!). The Index (divided by marques, coachbuilders, proper names, serial numbers) is commendably deep and common to both volumes.

Volume 2 is a seamless continuation of vol. 1 and does not have its own apparatus, even the chapter numbering continues consecutively. The only reason it is a separate volume is that it is solely devoted to the actual cars built, covering the histories of each of 35 GS models separately and additionally several T26GSL, T14LS, and T14 America models. It seems odd to devote fewer words here to vol. 2 even though it’s twice the size of the first but its contents is too highly specialized to be meaningfully commented upon. The level of magnification varies and depends on how much history survived or can be reconstructed today; certain ambiguities remain still. Considered are construction, coachwork, ownership and (if applicable) competition and concours highlights. In most cases the actual build sheet is reproduced, something the authors seem to want to apologize for as an eccentricity but is really par for the course in the case of cars as special as these. Lots of photos of restorations in progress and finished. It would have been useful to show profiles of all cars on one spread to illustrate how vastly different each looks.

We would be remiss if we didn’t praise the skills of the book designer who considered her work as much a labor of love as the authors did theirs. Overall layout and “period sensitive” colors, design elements, and display type impress.

Larsen’s next book will be on Saoutchik, the coachbuilder of the cover car. (That car now resides in the Mullin Automotive Museum, with different paint and trim, and is covered in vol. 2 of Michael Furman’s trilogy on that collection. To see it in its original form turn to Larsen’s book.)

Copyright 2013, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

Excellent review of just the sort of book we would all love to own, let alone an example of this relatively straightforward car. As a Riley owner, the appeal of the twin camshaft/short pushrod idea lingers.

There was a Lago Talbot saloon in the South Island of New Zealand, and I was told by one of two participants in what became a race between two friends, one in an R-Type Bentley and the other in the Talbot, between Invercargill and Queenstown. Willis Brown in the Bentley used a slight downhill bit to get up steam and won the “race.”