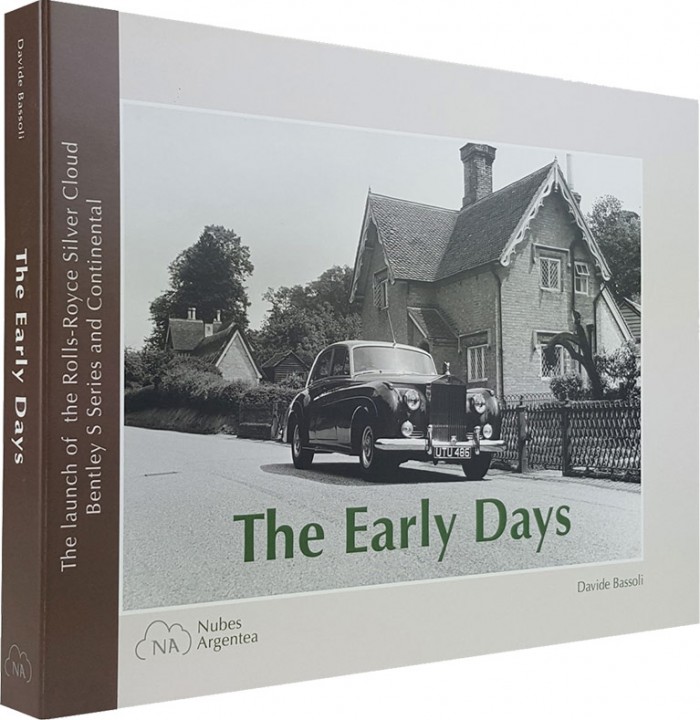

Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud, The Complete Story

It is this publisher’s intention to create an encyclopedic library of books (Crowood AutoClassics), each one covering a specific marque or model. This work is the 46th in a series that currently ranges from the AC Cobra to the VW Transporter, and the 8th to be authored by Graham Robson. Each edition is said to be written by an expert on the marque or model, thus providing a reliable reference tool as well as an introduction to the specific car. This book doesn’t quite accomplish the former, and as to the latter, it isn’t obvious just what this volume gives us that doesn’t exist already.

Graham Robson has a long career in the motor industry and was once competition manager for Standard Triumph during the 1960s. He has over 100 books to his credit and we know he is no stranger to this particular subject matter. It is, therefore, puzzling to note that his Cloud book repeats often-seen PR photographs and text that is little different from the company press releases, interspersed with the author’s own observations. Other than combining the material neatly between the covers of one book there is little else remarkable. Far from its title, The Complete Story, it appears anything but.

One cannot escape the impression that the author takes an unsympathetic view of his topic when he describes the Cloud series as both stylistically and technically obsolete right from its inception—an arbitrary verdict and a difficult pill to swallow. If one accepts Rolls-Royce’s design philosophy and their demographics, it should be said that the longevity of its product lines speaks to the fact that Rolls-Royce, with few exceptions, managed to meet its market’s expectations admirably and to build cars that would most please and satisfy the people who actually bought them new. It would be folly to expect an auto manufacturer to ignore the dictum of its paying customers. As early as 1948 R-R decided that the cars would have slab sides, without the distinct front and rear fenders that had previously been the norm. Coachbuilders were encouraged to test the theory; Mulliner produced a small run of Bentleys with “modern” styling, James Young built a few cars along similar lines, and Park Ward created the memorable Wentworth. Brave attempts—but they fell into the pool of public disregard. Hence the hasty retreat to a more classical appearance. Were it not for a car-starved UK at the time, these styling exercises may never have found buyers.

Admittedly, there are aspects of a company’s history that remain subject to informed interpretation but one is pained to read that chief designer John Blatchley “copied the Mulliner Lightweight” when designing the Cloud coachwork. Blatchley’s impeccable record of original, even trendsetting, design hardly deserves this criticism of plagiarism.

Even on the very unambiguous level of unimpeachable fact there are problems. It doesn’t instill confidence in the book to find the geography rearranged: the author places Crewe (where the Rolls-Royce plant is) in Staffordshire instead of Cheshire; and Graber, last we checked, was still a Swiss coachbuilder, not French.

Copyright 2000/2013, David Mulvaney (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter