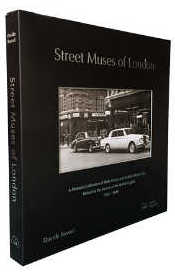

Austerity Motoring, From Armistice Until the Mid-Fifties

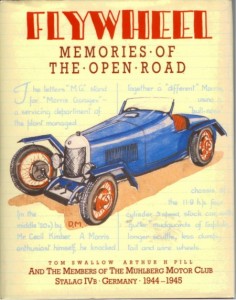

This book is a pocket history of England before, during, and after World War II as seen through an automotive lens. It is number four of the Veloce Publishing series “Those Were the Days” that now numbers 27 titles. The series title suggests nostalgia, and although Austerity does evoke this sentiment, hard facts of black markets, price gouging, and the general unavailability of cars are not ignored. But notwithstanding reminders of such considerations, the endurance, the inventiveness and the valor of a proud and courageous nation facing difficult times is what ultimately comes through.

War is declared in 1939. We find, at least concerning the motor industry, Britain was prepared. Plans had already been in place to construct “shadow factories,” factories “owned and financed by the government and managed by the motor industry” to produce airframes, aero engines and various military vehicles. The famous Rolls-Royce/Bentley, now Bentley, factory at Crewe was one of these. This ploy was successful. Commonly known wartime measures such as gas rationing and headlamp masking are illustrated throughout the book, but what is more intriguing are the less known schemes:  Natural gas was used to fuel some cars, with large gasbags attached to the roofs (which rendered the cars “unstable in windy weather”). Since “polished cellulose reflected light and could be easily detected from the air” the Ministry of Home Security “considered having all private motor vehicles camouflaged”—which was ultimately only realized on a very small scale. And, immediately after the war, there was a consideration to nationalize the car industry and “a call to produce a ‘national car.’” Period photographs and advertisements illustrate these products and ideas.

Natural gas was used to fuel some cars, with large gasbags attached to the roofs (which rendered the cars “unstable in windy weather”). Since “polished cellulose reflected light and could be easily detected from the air” the Ministry of Home Security “considered having all private motor vehicles camouflaged”—which was ultimately only realized on a very small scale. And, immediately after the war, there was a consideration to nationalize the car industry and “a call to produce a ‘national car.’” Period photographs and advertisements illustrate these products and ideas.

In the immediate postwar era, automotive England dealt with various changes and problems. Women, because of their wartime experience in servicing and repairing military vehicles, were “more widely employed” in the automotive industry. England’s need for an inflow of foreign currency mandated that she “export or die,” the title of the book’s second chapter. By 1948 the government decreed that “steel supplies would only be available to those manufactures exporting 75 percent of their output,” and this too was a successful move in that it generated the needed cash.

Cars were of course made for the home market, and the more affordable models, some of them three wheelers, appear to today’s eyes amusing, toy like. The photograph of a family of four, Father in a coat and tie, Junior in a shirt and tie and Mother and Sis in summer frocks, picnicking beside a tiny Reliant Regal could be a Monty Python sketch. One cannot help but wonder how the family and the food basket could ever fit. But, on the other hand, one cannot help but admire the propriety and the gumption of such a family, unwilling to let adversity or a small budget hamper their enjoyment.

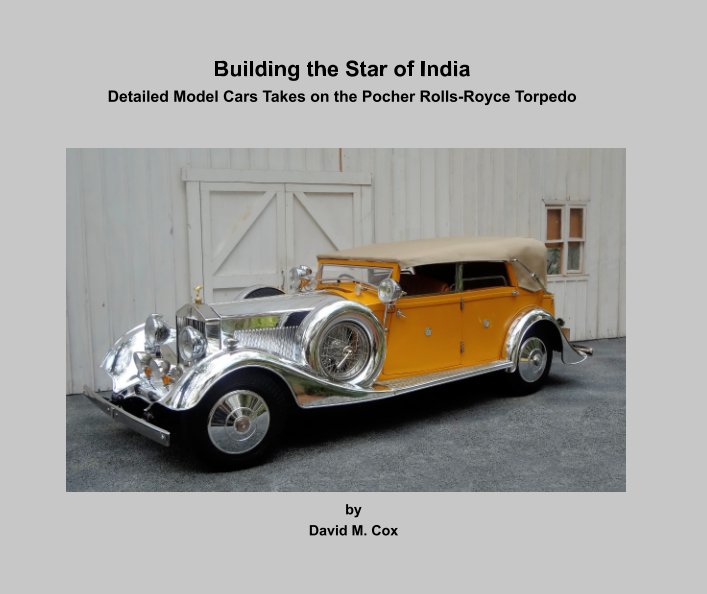

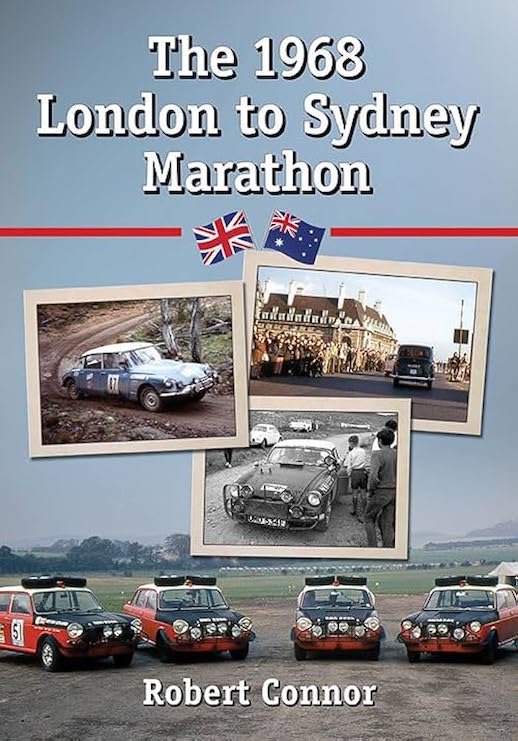

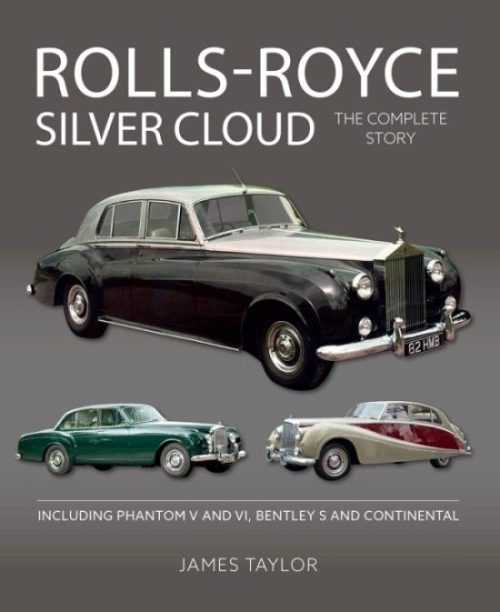

Austerity’s last chapter deals with the fact that “there remained a select few who were able to afford the best the motor industry could offer.” The various photographs, illustrations and advertisements of such marques as Armstrong Siddely, Daimler, Jaguar, Austin (the Princess with Vanden Plas coachwork), Bentley and Rolls-Royce afford much pleasure to the automotive enthusiast. This chapter also considers how racing and rallying eventually were reestablished, but here the book is shy of photographic illustration.

At the end of that era comes a crowning achievement: the world’s most expensive car of its time, the 1952 Bentley R Type Continental—and another calamity: the Suez Crisis.

The books in this Veloce series, Austerity among them, are compact and relatively inexpensive and thus the pages sometimes seem crowded and the illustrations not quite as clear and crisp as one would want. But this is a mild complaint as the overall virtues of the book warrant attention and praise.

Copyright 2012, Bill Wolf (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter