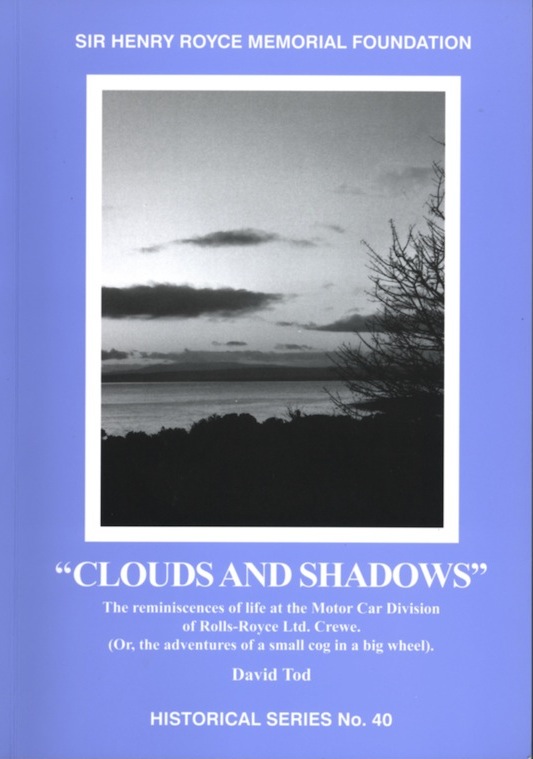

An Account of Partnership – Industry, Government and the Aero Engine

The Memoirs of George Purvis Bulman

Major George Bulman played a crucial role in Britain’s embryonic aircraft engine development business. As a government employee, Bulman’s responsibilities included the determination of whether an aircraft powerplant was fit for Royal Air Force service. His official title was Director of Engine Development and Production which means his responsibilities ranged far and wide.

This autobiography was written in the late 1960s but for various reasons was never published. It is thanks to M.C. Neale, one of Bulman’s successors, that this manuscript saw the light of day lo these many years later. And what a wonderful account it turned out to be.

To prepare the reader for what is in store, Neale wrote a lengthy and informative introduction. Although Neale’s writing style could be perceived as irritating due to chopped-up sentences and at times, an awkward grammar style, the intro is highly recommended reading and well worth the effort.

At the onset of World War I, not surprisingly, the British had no organized aircraft engine capability, therefore the responsibility for developing one was thrust upon the government. It is during this embryonic stage that Bulman enters the picture; he remains in engine development and production until his departure in 1942. During his tenure, Bulman rubbed shoulders with all the movers and shakers of British aviation including his close friend Frank Halford, also Ernest Hives, Rod Banks, Wilfrid Freeman, Winston Churchill, Dr. Roxbee Cox, Harry Ricardo, Roy Fedden, and many other luminaries. His involvement with the Schneider Trophy races sheds more light on this fascinating contest of national pride and honor. The story of the infamous head and bank change on the Rolls-Royce R engine the night before the 1929 race has been well documented. But the manner in which the head and bank assembly was changed has never before been dealt with. Even Bulman’s text does not get into any details but a painting depicting the job occupies a full page of the book. Normally, when a bank is removed from a 60 degree V-12, the engine is rotated 30 degrees in order to remove the bank vertically. With the engine mounted in the aircraft, this 30 degree tilt becomes problematic. However, in a scene similar to, “if Mohammed will not go to the mountain then move the mountain to Mohammed,” the Rolls-Royce mechanics charged with replacing the problematic bank assembly tilted the entire aircraft (a Supermarine S6B) the requisite 30 degrees. Fascinating stuff!!!

As war clouds gathered in the mid to late 1930s, it was thanks to Bulman’s proactive approach to engine manufacturing that the British were prepared; or at least as prepared as one can be with such a calamitous event about to overtake the entire world. Thank goodness Bulman got the British car industry geared up for production of aircraft engines. And remember, as today, the top executives of the 1930s were an egocentric bunch to whom the term “team player” as it pertained to cooperating with their bitterest rivals was anathema. Nevertheless, Bulman managed to get them to pull together for the national good.

After reading Bulman’s account, it was obvious the war took a terrible toll on him, even though he didn’t always admit to such in the text. At times, a reader needs to read between the lines to understand the implied messages. One cannot help but admire his charity towards those who would stab him in the back or otherwise do him political harm. Having a top-level government job clearly thrust him into the inevitable politics that came as part and parcel with such a position. With one exception, he had nothing but praise for those he worked with and worked for. The one exception was Frank Whittle. Perhaps we will never get the whole truth on this sordid episode. But the fact of the matter is, Whittle received a patent for the jet engine in 1930, handing the British a 10-year lead in gas turbine development. By the early 1940s the British were lagging behind the Germans due to ineptitude and a lack of appreciation of what this new technology was capable of. This tremendous lead was frittered away. Bulman has to take at least some responsibility for this sorry state of affairs but instead he blames Whittle and his difficult personality. All accounts seem to support the contention that Whittle was difficult to work with, nevertheless, when a world-beating technology comes along it is incumbent upon those in power to exploit this new technology to the full, regardless of the difficulties in dealing with “unique” personalities. The British missed the boat on this one—big time.

Bulman’s downfall appears to have been the result of protracted problems with the Napier Sabre. In all fairness, he was given a classic “Mission Impossible” with this complex and problematic engine. Exacerbating Bulman’s situation was the apparent lackadaisical attitude Napier executives demonstrated. No wonder the US turned down manufacturing rights to this complex nightmare. Perhaps Bulman’s close association with Halford, the Sabre’s creator, had a lot to do with his fall from grace. According to Bulman’s account, the Sabre was finally coming out of the woods and turning into a useful engine for RAF Typhoons when he was unceremoniously posted to a different position. Rod Banks replaced Bulman and received all the accolades for “fixing” the Sabre problems. I find it interesting to read Bulman’s account and compare it with Banks’ account—it’s almost as if we are reading about two different stories. Likewise, comparing Whittle’s biography shows a different spin on how events transpired. Freeman’s biography probably adds yet another angle to this story.

It was somewhat surprising to see a number of errors in the book that could have easily been corrected in the editing stage. The photo of a Hispano Suiza V-8 shown upside down is a real blooper. An even more egregious error is the photo of government and industry big shots supposedly looking at a Napier Sabre. The photo actually shows a Napier Dagger, a very different engine. Bulman leaves the reader with the impression that the Rolls-Royce Eagle 22 was an exact copy of the Napier Sabre. In fact the Eagle 22, although conceptually the same as the Sabre, was a totally different engine.

Development of the two-stage Merlin is covered. These were 60 series Merlins but the text incorrectly describes the first two-stage Merlin as the Merlin XX. In fact, this latter engine was single stage engine.

Overall, this book represents a great read with all the intrigue and politicking that one could ever envision. As all books from the Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust Historical Series, this is one well worth buying and as always at a bargain basement price.

Copyright 2013, Graham White (speedreaders.info).

White heads the Aircraft Engine Historical Society (AEHS) for whom this review was originally written.

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter