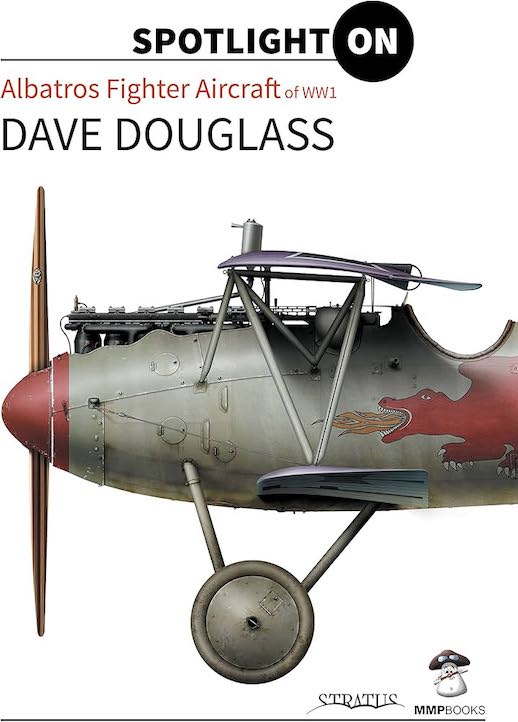

Albatros Fighter Aircraft of WWI

by Dave Douglass

by Dave Douglass

“The Albatros is perfect for the genre of aircraft profile art, not only because of its beautifully finished fuselage of varnished plywood, painted metal fittings, pleasing shape, and variety of factory finishes, but also because of its myriad Jagdstaffe [sic] and personal markings.

This little Mercedes-powered German fighter had only a short operational career but made up the bulk of the German and Austrian fighter squadrons for the last two years of World War I. It was supposed to do better than the Fokker Eindecker against the Nieuport Bébé and others but it struggled.

Several versions—I, II, III, V, and Va—followed each other in quick succession, often only months apart, and all are shown in this book. “Shown” is the operative word as there is no text other than a general introduction and captions for the drawings. This book is the first in a new series called “Spotlight ON” whose main thrust is to be a resource to modelers.

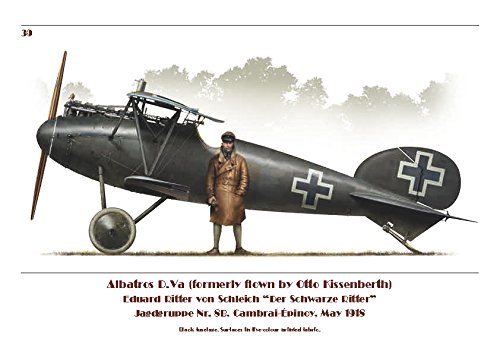

There are 39 profile views in color, created on the computer, printed in landscape format, all at the same size and only of the left side. Two are of aircraft on the ground, one of which has a pilot standing next to it which gives a useful idea of scale. This book clearly presumes that the reader is familiar with the topic, i.e. the aircraft, and also modeling or even rendering techniques. The Introduction, for instance, makes mention of “frisket masking” which won’t mean a thing to anyone who doesn’t apply colors to surfaces. (In airbrushing, which is the context here, a frisket is an adhesive-backed plastic sheet that is applied over the entire object and then you remove those parts, by cutting into the sheet, you want to work on at that specific stage.)

Since the only real text is found in the captions, and since the press release calls them “very comprehensive,” it must be said that this is a mixed bag. They are only comprehensive inasmuch as they contain a date, pilot particulars if known, and color info. They also give a city location but not country so if you don’t know if, say, Ugny or Eswars are in France but Heule or Marckebeke in Belgium, this information is not really as comprehensive as it could/ought to be.

Moreover, since this book by its very nature is aimed at people who deal in micro detail it is odd that in at least three cases the number painted on the tail doesn’t match the one called out in the caption! Then there’s the case of one and the same aircraft being shown twice (p. 10/11), in the same month, once with German markings and then, after being captured, with French. This is neither here nor there—although it would have been useful to show these two next to each other—but why does the captured plane now have a different wheel and tire?? It is not impossible that the landing gear got damaged and the French stuck a new or scavenged wheel on, but why not explain such deviations? In another case (p. 40/41) two 1918 D.V models are shown but their gross weight placards are not identical. Not likely!

It would be nice to have explanations for these and other issues—but it would be nicer still if there was no need for them in the first place! The reader’s confidence in the author is not boosted by seeing, right on the first page, the German word for fighter squadron (see quote above) misspelled every single time. (It is ok only in the Bibliography.) That confidence would come in handy on, for instance, p. 20 where the D.V prototype is dated “September 1916” which seems dubious since the D.III didn’t come on-line until December 1916. Speaking of this prototype, it seems a tall order to expect even the fairly well-informed reader to simply “know” that the shape of the rudder on only that one example matches the standard rudder of D.IIIs built at the Johannisthal factory whereas D.V production examples switched to the enlarged rudder that the D.IIIs built at Ostdeutsche Albatros Werke sported. While the prototype is drawn here correctly, not explaining such detail seems a totally lost opportunity to school readers’ eyes. Ditto for a plethora of differences in engine plumbing, spinners, various apertures, even headrests which ought to be fairly obvious but really aren’t unless pointed out. You will have to keep your eyes peeled all the time! (And just maybe you’ll spot the one plane out of 39 that is drawn with an access cover on the fuselage in the open position . . .)

It would be nice to have explanations for these and other issues—but it would be nicer still if there was no need for them in the first place! The reader’s confidence in the author is not boosted by seeing, right on the first page, the German word for fighter squadron (see quote above) misspelled every single time. (It is ok only in the Bibliography.) That confidence would come in handy on, for instance, p. 20 where the D.V prototype is dated “September 1916” which seems dubious since the D.III didn’t come on-line until December 1916. Speaking of this prototype, it seems a tall order to expect even the fairly well-informed reader to simply “know” that the shape of the rudder on only that one example matches the standard rudder of D.IIIs built at the Johannisthal factory whereas D.V production examples switched to the enlarged rudder that the D.IIIs built at Ostdeutsche Albatros Werke sported. While the prototype is drawn here correctly, not explaining such detail seems a totally lost opportunity to school readers’ eyes. Ditto for a plethora of differences in engine plumbing, spinners, various apertures, even headrests which ought to be fairly obvious but really aren’t unless pointed out. You will have to keep your eyes peeled all the time! (And just maybe you’ll spot the one plane out of 39 that is drawn with an access cover on the fuselage in the open position . . .)

For people who need books like this, profile views are important but they don’t help with markings on, say, wings.

This book, this series, is clearly a nice idea and serves a purpose—but it could be made more useful still!

Copyright 2025, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter