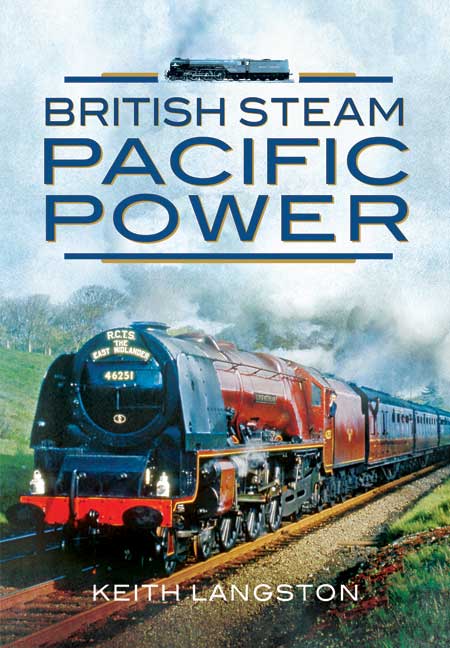

British Steam – Pacific Power

“In modern times we have rightly marveled at space travel, air travel and electronic wizardry of all kinds but way back in the days before computers etc. the combining of all the various skills to create a living breathing steam locomotive, from a drawing on a piece of paper, should be considered at least as impressive in its own right.”

If someone told you the last newly built steam loco first ran in 2008, would you bet on it? Weren’t they phased out in the 1960s? Well, yes and yes.

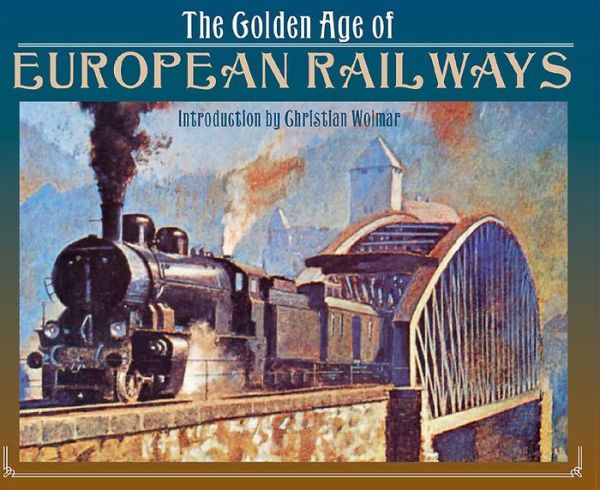

If you have an affinity for things mechanical, large steam locos are about as captivating as it gets. They need to be large to do the work: a passenger locomotive needs to reach high speed but doesn’t need to pull a lot of weight (in railroading lingo it doesn’t need to have “high tractive force”) but the opposite applies to a freight locomotive. In either case, since water heated into steam expands its volume 1600 times, you need to have a big boiler and a big coal grate and a big coal tender and a big . . . everything. And the Pacific class of steam locos is big!

Both the name and the typical wheel arrangement (4 in the front, 6 in the middle, 2 in the back, denoted as 4-6-2) are thought to be of American origin. Any of the famous express trains you could think of—the streamlined bullet trains of their day—probably had a Pacific up front: the Flying Scotsman, the record-setting Mallard, and that 2008 Tornado we teased you with above which wasn’t just a “because we can” retro-engineering exercise but is an actual revenue earner.

This book is part of this publisher’s series on British Steam. In fact, there’s a Scottish Steam title as well, also by this author but not (yet?) built out into a series. Coming from a railway family, Langston has had trains on the brain for a long time and contributed to many books and, increasingly, is writing his own.

This handy book begins with an explanation of the 4-6-2 type, making reference to the fact that it is subdivided into several classes. Fifteen important engineers are then introduced, in the order in which their creations entered service. If these few pages were any longer it’d be hard to find a specific name; on the other hand, Langston’s arrangement allows for a sense of progressive development to permeate the reader’s mind. Typical for this publisher, there is no Index.

The bulk of the book then discusses 28 specific machines in chronological order, from the first 4-6-2, The Great Bear of 1908, to 1954’s Duke of Gloucester before dealing with that 2008 outlier. The text presents developmental highlights, service life, upgrades or modifications (which, in some cases, meant reconfiguration to an entirely different class), and even paint schemes and markings. Blue tables present class specs, green ones offer loco-specific particulars such as numbers, names, yard, and dates.

Photos are plentiful (no line art), many previously unpublished, and supremely well captioned to draw attention to detail not easily noticed without such prompting. It helps to have some familiarity with the lingo, lest, when directed to look for “the shunter’s pole on the buffer beam” you don’t know where to cast your eye. There’s also some technical detail that requires of the reader to either know, for instance, the difference between a Schmidt superheater vs. a Swindon—or to simply keep reading.

Copyright 2025, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter