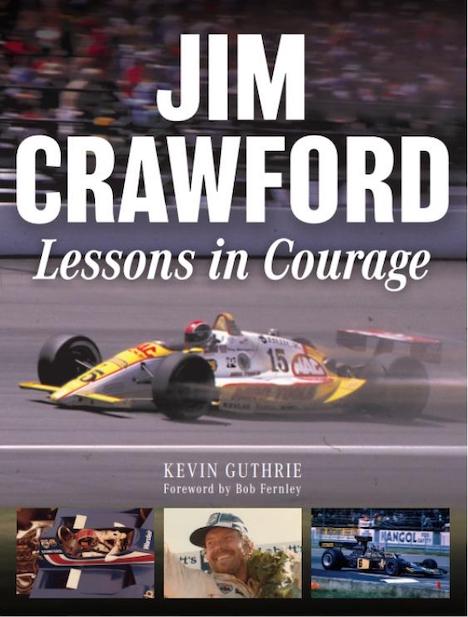

Second to One: All But For Indy

by Gordon Kirby & Joseph Freeman

by Gordon Kirby & Joseph Freeman

“The current phenomenon of lost recognition in American automobile racing seems to be an unfortunate trend and particularly unfair to the greatest athletes of historically one of the greatest American sports.”

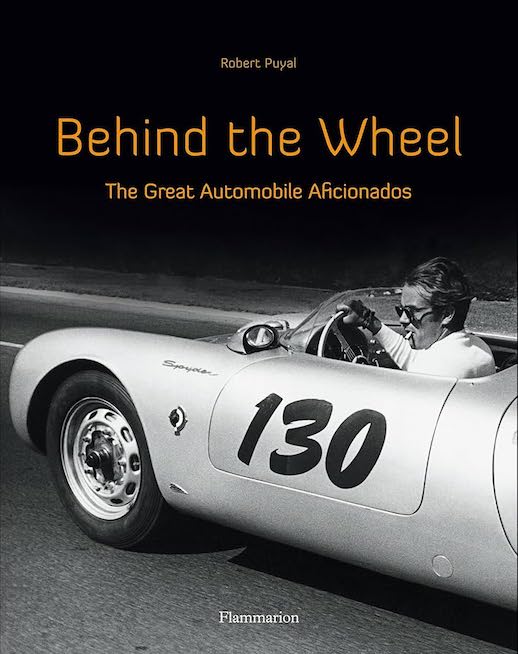

Whether it’s Grands Prix or spelling bees, if only one person can be the winner, is everyone else a failure—in any sense other than semantically? Is the person who came second a lesser looser than lower-placing contenders?

This is a fundamental question, at the individual and the societal level. Civilizations stand and fall with the answer to that question. This book does not attempt to answer it, although it considers the American psyche to be particularly susceptible to this all-or-nothing mentality, but it offers a glimpse into the moments when an Indy 500 victory slipped away from one and fell to another.

Professional motorsport is a complex undertaking and the work of many hands, further complicated by factors that are beyond anyone’s control at the time such control is required: a misaligned ply during tire construction, a shift in weather, an inopportune yellow flag, a bad night’s sleep, a nanosecond of distraction, a slow pit stop. These things and a thousand more can conspire to change the course of events, but however unpleasant they are acceptable because . . . “stuff happens.” If it happens often, how long before you take it personal and begin to wonder about fate or bad luck?

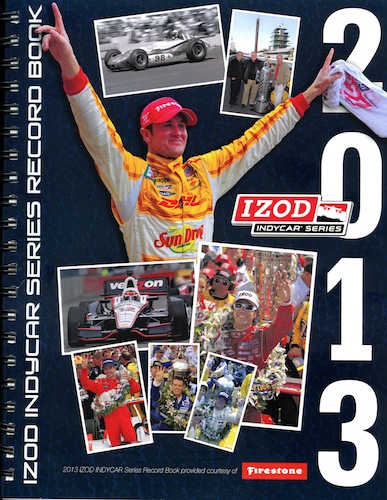

Both the drivers whose comments open and close the book—Michael Andretti and Tony Kanaan—have been through that wringer many, many, many times. If this book had been written a year earlier, Kanaan might have been one of the chapters but, as the authors write so cleverly, he managed “to drive himself out of our book” just in time. It only took twelve attempts.

Forty drivers between 1911 and 2013 are discussed, each one in an individual chapter. While the focus always is on the specific race in which they came second, a driver’s overall career achievements are discussed at some length because the whole point of this book is that a driver had to be eminently capable to even be invited to the grid to compete. Looking “only” at second places made a 344-page book in and of itself. Any number of pages could be added to cover the rest of the field; in fact, this book ends with the words “To be continued.”

This publisher’s primary mission, especially with the American Racing History Series, is to fill gaps, and at a scholarly level, meaning properly researched and expanding the record. The raw facts and stats the book relates are of course part of the known, public record and are therefore not “new.” Their virtue here is in being arranged conveniently in one place to examine a particular thread of the tapestry of racing history. One way in which Racemaker advances the record is by introducing new photographic material from its vast archive. On that score alone this book can justify its existence, and its price.

The bios are presented in chronological order, a straightforward choice. Different eras are bridged in the form of six separate commentaries, also a straightforward approach. What is not at all straightforward is why on the Table of Contents—which makes a surprise appearance after ten pages of introductory material—both the bios and the bridge chapters are all set in the same font at the same size, indistinguishable from each other. How does this help the reader? A book, too, is the work of many hands and on that score it must be said, yet again, that there is a regrettable lack of typesetting, editorial, and proofreading competence. From poor line breaks to an entire “side head” (consisting of name, year, gap to winner) duplicating the preceding race’s particulars (p. 257 vs 261) what would otherwise be an excellent book is tainted by the sort of shoddy QC that is incompatible with the values of an ambitious and important publisher like Racemaker Press.

Appended is a description of 46 second-placed cars by year, driver, name, noteworthy construction features, and whereabouts. There is a Bibliography but it seems oddly spotty until you deduce that this must be list of sources the authors are quoting in the text. No Index, which, in this sort of book, would probably have grown to unmanageable size.

Copyright 2015, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter