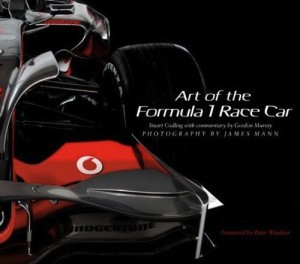

World Championship

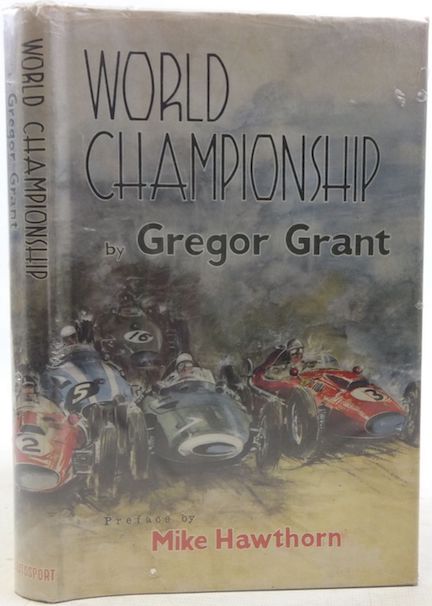

When World Championship by Gregor Grant (b. 1911), the founder and editor of the motor racing weekly Autosport and an amateur racer himself, appeared in May 1959, it was quite probably the first such book—at least in English, as far as I have been able to determine—to devote itself entirely to the Championnat du Monde des Conducteurs, the World Championship for Drivers, which had been created by the Commission Sportive Internationale in the Fall of 1949. This followed, not so incidentally, the successful introduction of a world championship series for motorcycle racing during the 1949 season by the Fédération Internationale de Motocyclisme. As in the case of the FIM’s world championship, this CSI world championship was instigated by the organization’s Italian delegation.

Of the five classes that competed under the inaugural season of the FIM world championship, the 125cc (Nello Pagani, Mondial) and 250cc (Bruno Ruffo, Guzzi) classes were won by Italian riders and machines. The remaining three classes in the 1949 FIM world championship, the 350cc, 500cc, and sidecar were all won by British riders and machines: Freddy Firth (Velocette), Les Graham (AJS), and Eric Oliver/Denis Jenkinson (Norton), respectively. Similar success by the British during the inaugural season of the new CSI world championship was, however, not anticipated, the Italians being very much the favorites in that sphere.

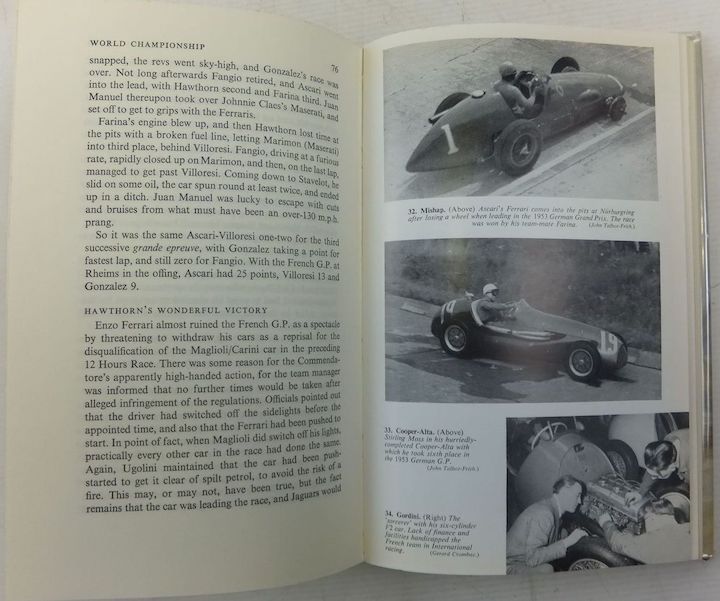

The format of Grant’s World Championship is really quite straightforward. It opens with a Preface by Mike Hawthorn (written in December 1958, a mere month prior to his death in a road accident on the Guilford Bypass), followed by an opening chapter on the world champions (Farina – 1950, Ascari – 1952/1953, Fangio – 1951/1954/1955/1956/1957, and Hawthorn – 1958), a chapter on the cars used by the world champions (Alfa Romeo Tipo 158 and 159 – 1950/1951, F2 Ferrari – 1952/1953, Maserati 250/F1 – 1954/1957, Mercedes-Benz W196 – 1954/1955, D.50 Ferrari (Lancia) – 1956, Ferrari Dino 246 – 1958), chapters on each of the championship seasons, 1950 to 1958. Finally, there is a listing of what Grant refers to as the Grandes Épreuves, that is, the world championship events held over the nine seasons covered in the book, 1950–58. For schoolboys in 1959, this latter feature was almost manna from the heavens. This listing included the first five finishers and who set the fastest lap for each event, in other words, everyone who earned world championship points. To appreciate this seemingly small thing one needs to realize that this sort of information did not grow on trees back then! While one might have been able to create a listing of the races that comprised the world championship for each of its seasons, along with such information as the venues and the winners and the marque of car used, everything after that was usually a challenge.

Finally, there is a listing of what Grant refers to as the Grandes Épreuves, that is, the world championship events held over the nine seasons covered in the book, 1950–58. For schoolboys in 1959, this latter feature was almost manna from the heavens. This listing included the first five finishers and who set the fastest lap for each event, in other words, everyone who earned world championship points. To appreciate this seemingly small thing one needs to realize that this sort of information did not grow on trees back then! While one might have been able to create a listing of the races that comprised the world championship for each of its seasons, along with such information as the venues and the winners and the marque of car used, everything after that was usually a challenge.

Also, a Guinea was not an insignificant amount of money for a schoolboy in those days. Book Lust for works such as World Championship, Norman Smith’s Case History, Alf Francis’ and Peter Lewis’ Alf Francis: Racing Mechanic, 1948–58, The Vanishing Litres: 30 Years of Grand Prix Racing by Rex Hays, John Fitch’s Adventure of Wheels, and, later, A Story of Formula 1 by Denis Jenkinson (or “DSJ” as he was known in each month’s issue of Motor Racing) was real for legions of schoolboys in those years. For those on the Other Side of The Pond, it was even more challenging, of course.

Grande Épreuve translates into English, as best as I can in my very rusty French can figure, as “great trial” or basically a big sports event. The Automobile Club de France and then the Association Internationale des Automobile Clubs Reconnus, now the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile after a post-World War II name change, along with the CSI, when it came along in 1922, used the term to denote the major motor sport events of the day, such as the national Grands Prix of the members of the organization. The premier among these was, of course, the Grand Prix de l’Automobile Club de France, first held in 1906, with some creative tinkering by the ACF pushed back to the Paris to Bordeaux to Paris Trial of 1895. Prior to World War II, interesting enough, it was the Tourist Trophy that was listed as the Grande Épreuve for Great Britain, so such events could be held for something other than Grand Prix machines.

It is this notion of an event having to be considered as one of the relative handful of Grandes Épreuves in order to be included in the Championnat du Monde des Conducteurs that Grant, as they say, “comes a cropper.” The Grande Épreuve for the United States during this time was the 500 mile International Sweepstakes race held on Memorial Day at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. From 1950 until 1960, eleven years, the International Sweepstakes race was a part of the world championship. It is, however, almost completely absent from this book. It is certainly not listed as being a part of any of the championship seasons for which Grant provides that information which was once so important for schoolboys. After being mentioned as one of the Grandes Épreuves accepted for inclusion for the 1950 world championship, the Indianapolis 500 mile race then simply disappears for the rest of the book and the championship.

For that matter, it is still rare today to find the Indianapolis races of 1950–1960 included or discussed in books focusing on the world championships of 1950–1980 and the one currently in place since 1981. The Indianapolis race is dismissed as being a remote event, not really a “Grand Prix” in the usual (that is, European) sense and not even run to the International Racing Formula 1, as the CSI so quaintly put it in its regulations, from 1954 to 1960. Overlooked in this line of thought is the overlooked loophole that until the 1961 season, there was not a requirement that an event counting towards the world championship, a Grande Épreuve, be held using the cars conforming to the current Formula 1. Odd, yes, but as we are reminded from time to time, the past was different back then.

Is there any reason to take the time today to read an old book like this? I would suggest yes. (It is still easily found and not expensive.) It certainly provides an excellent window into the Zeitgeist of the era. Whatever the weaknesses or merits of World Championship, as the editor of Autosport the words of Gregor Grant definitely meant something at the time. His words resonated not merely in Britain but also among the community of racing enthusiasts in America who followed European road racing.

While not that many copies of World Championship may have reached the shores of America, most of those that did wound up in the hands of people who either wrote about racing then or would later.

Won the “Autosport Magazine Gregor Grant Award” for lifetime achievement in motorsport which is awarded annually at the Autosport Awards.

Copyright 2017, Don Capps (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter