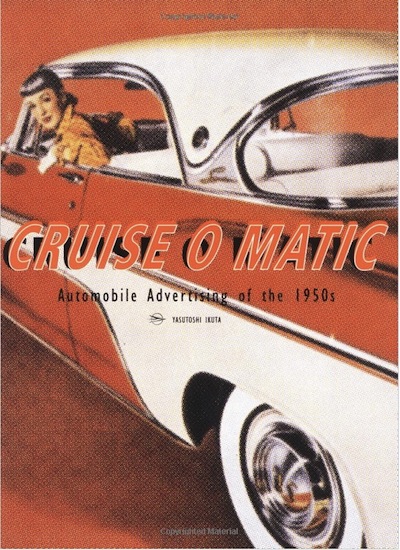

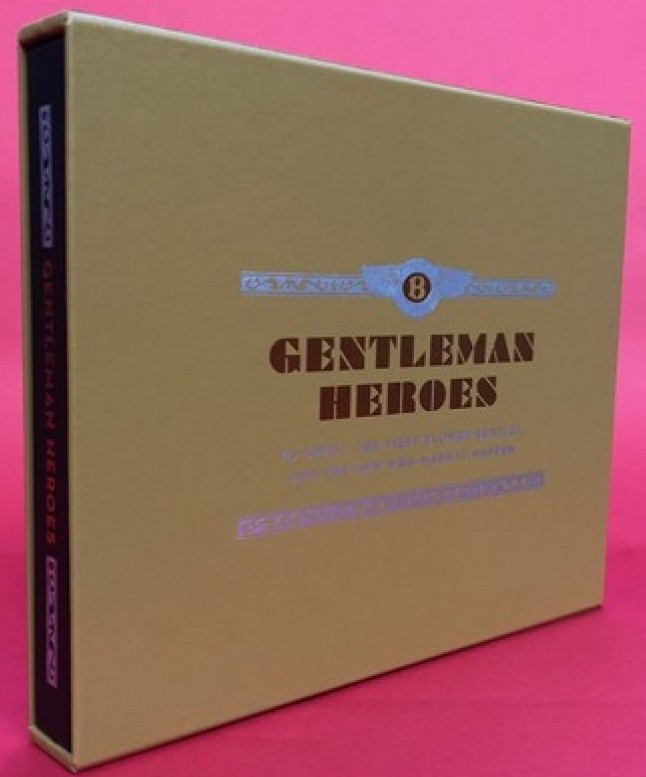

Northeast American Sports Car Races 1950–1959

by Terry O’Neil

by Terry O’Neil

“The early 1950s was a time when the majority of people in America had never seen a motor race. It was something that happened in Europe, or so they thought. When British and other European sports cars began appearing along the leafy glades of suburbia, people looked quizzically at them, possibly wondering whether they had a purpose.”

This book documents the progression, and the reasons behind it, from amateur to professional sports car racing in North America over the course of a decade. This era was rife with change in another racing-related aspect as well, the emergence of purpose-built racetracks that began to replace road circuits. In the US, as elsewhere, former military airfields provided an interim home to the racers who gladly availed themselves of the existing airplane-sized taxiways and service facilities. (Oddly, the book doesn’t mention the role of U.S. Air Force General Curtis LeMay in this. A racing enthusiast himself, it was thanks to his efforts that Strategic Air Command bases were repurposed for use by the Sports Car Club of America.)

Although it was neither the first nor the only sanctioning body for road racing, rallying, and autocross in this country, the SCCA (formed in 1944 and rooted in the Automobile Racing Club of America founded in 1933 and dissolved in 1941) features prominently in O’Neils story because it was the Big Kid on the Block—the “block” here being California and that part of the US east coast that is comprised of the northeastern states north of the Mason-Dixon line. O’Neil’s focus, at least for the purposes of this book, is only on the latter because the California racing scene has been widely covered already.

If you know his 2006 book The Bahamas Speed Weeks you already have a sense for his approach and presentation: lots and lots of tables strung together by narrative covering people, cars, and racing. Given that his personal interests lie in the Ferrari world (after a professional life in sales and marketing at the Rootes Group and British Leyland; he is a Brit, incidentally) one can only wonder what it is about North American sports car racing that motivates him to willingly seek out the gargantuan task of tunneling through piles of paper to reconcile conflicting, often haphazardly kept primary sources so as to give his fellow man as complete a reference-level resource as the state of current knowledge permits.

Before you balk at the book’s $200 price tag and say that all this could be found for free on the Internet, consider that the cardinal flaw of web-sourced data is that much of it is not vetted. And even if it is, provided it exists at all, the data of a myriad of minor and major events is unlikely to be in any sort of uniform format that would allow apples-to-apples treatment. Moreover, O’Neil strives to account for all entrants, not just the top finisher/s. If you place any value on your own time, and want the reassurance that someone with a brain looked at the data and worked out the kinks, $200 doesn’t look so bad!

The base statistical data used by O’Neil comes primarily from newspapers, magazines, and various libraries and archives. Where written records were incomplete, especially in regard to less prominent venues or lower-placed finishers, sources such as photos were analyzed to gather additional data about entrants. The International Motor Racing Research Center at Watkins Glen is an obvious resource, and its historian since 2004, Bill Green, wrote the short Foreword. Green is also Watkins Glen track historian since 1968 and was SCCA deputy archivist 1984–1995 and his private collection is legendary, as it should be, considering that he started it at the tender age of eight!

Each year is covered in a separate chapter. The first year, 1950, is obviously given a more extensive exposition as a good deal of context to the preceding years has to be established. The race events are described in chronological order, from a few sentences to several pages. The venues are described, as are personalities, cars (only in brief!), politics, regulations and the sport’s general growing pains. The race commentary proper is of necessity reduced to brief highlights. Hundreds of tables of race results make up half the book. As alluded to earlier, their principal virtue is in presenting the data in a like manner throughout (location, distance, class, starters, winner’s time, average speed and then race number, car make, chassis no., driver, and position). Data that is unknown is indicated by blanks, and O’Neil hopes to progressively flesh out the picture in future editions.

Track maps, race posters, and miscellaneous ephemera add visual interest. A large number of the many, many photos are new to the record as well. They come from a variety of amateur and professional sources—with a commensurate variety in quality and composition. Their purpose in this book is first and foremost documentary; don’t expect art here. They are pretty much evenly divided between on- and off-track activity. All are thoroughly captioned, credited, and rather well reproduced.

The Index is a bit on the light side and divided into people, organizations, and venues (no cars, being as they are peripheral to O’Neil’s focus on the overall history of a specific type of racing in a specific time and place).

PS: Eagle-eyed readers who notice that two images (covers of race programs; photo only, no text) are used twice but each time with a different race track named in the caption should know that it was not uncommon for the same, generic brochure to be used repeatedly.

Copyright 2010, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter