Classic Engines, Modern Fuel: The Problems, the Solutions

“Why doesn’t my lovely old car run as well as I remember it? It must be this stupid modern fuel.” Myths abound, particularly in this age of readily available information, quality thereof unspecified. One vividly remembered episode took place during the hot and dry summer of 1995/96 in New Zealand, shortly after unleaded fuel became mandatory. One hero drove his 6C 1500 cc supercharged Alfa Romeo through the notoriously dusty Molesworth Route, sans air filter. The engine became unwell, and our gallant Alfisti was going to sue the fuel company. Good luck with that.

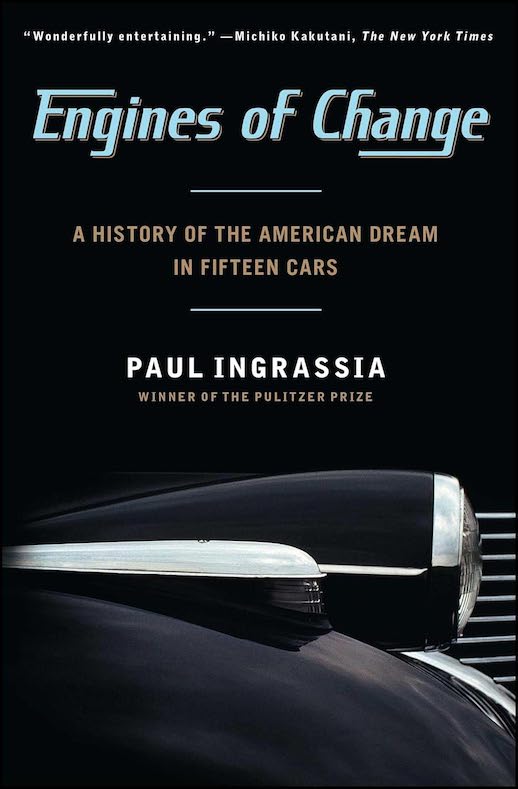

Unleaded fuel is here to stay, and so is an Ethanol content; this book sets out to separate fact from fiction, and, best of all, provide us with options and solutions. Since this attempts to be a review, rather than a report, the reader is best left to absorb the suggestions and solutions, often good common sense, that Ireland proposes. Since the book is addressed to the driver, rather than the concours entrant, some modifications from original are proposed. He aims to address how best to cope with stop-start driving in modern conditions, rather than the now rare opportunities to travel at the 3,000 rpm ideal at which most “classic” engines are happiest.

Unleaded fuel is here to stay, and so is an Ethanol content; this book sets out to separate fact from fiction, and, best of all, provide us with options and solutions. Since this attempts to be a review, rather than a report, the reader is best left to absorb the suggestions and solutions, often good common sense, that Ireland proposes. Since the book is addressed to the driver, rather than the concours entrant, some modifications from original are proposed. He aims to address how best to cope with stop-start driving in modern conditions, rather than the now rare opportunities to travel at the 3,000 rpm ideal at which most “classic” engines are happiest.

Paul Ireland was 16 when he bought his first car, a 1949 MG TC. Although his career has been desk-based after a PhD in Experimental Nuclear Physics, his family are mostly “proper” engineers, and Ireland has always maintained and restored his cars himself. After tetra-ethyl lead was removed from gasoline in the late 1980s, his MG didn’t run as well as he remembered, and he spent many years investigating the whys, hows, and wherefores. Eventually this led to a study by the School of Mechanical, Aerospace and Civil Engineering at his alma mater, Manchester University, with support of faculty and a team of six students; the Federation of British Historical Vehicle Clubs; various MG groups; and oil and other industries; they all contributed to his project, and the findings are now published in this book. Sources are all acknowledged, and Ireland is donating all royalties from his book to helping with children’s education in the developing world. What’s not to like?

The MG TC has a 1250 cc push-rod four-cylinder engine known as the XPAG, and, as well as Ireland’s familiarity with them, it is of an ubiquitous long-stroke design easily understood by most tinkerers with old cars. It was built in large numbers for almost thirty years, even in utility form right through the Second World War. A rebuilt XPAG engine was installed on a test bed, and connected to a wide variety of research devices.

The MG TC has a 1250 cc push-rod four-cylinder engine known as the XPAG, and, as well as Ireland’s familiarity with them, it is of an ubiquitous long-stroke design easily understood by most tinkerers with old cars. It was built in large numbers for almost thirty years, even in utility form right through the Second World War. A rebuilt XPAG engine was installed on a test bed, and connected to a wide variety of research devices.

Chapters such as “Suck, Squeeze, Bang & Blow” and “Carburettors” give a useful refresher course for those of us who thought we remembered it all, and will bring back rueful memories of struggles with recalcitrant machinery, and the wonder that we ever got them to run as well as they did.

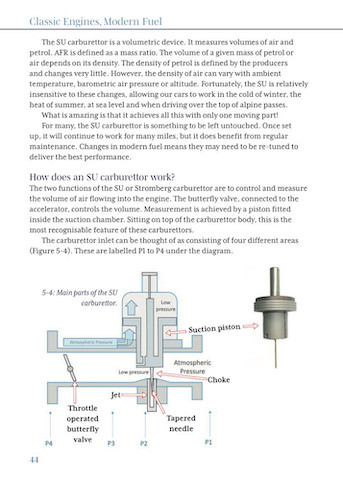

The XPAG used two SU carburettors, and those variable jet instruments, and the closely related Stromberg, are considered rather than the fixed-jet Solex, Weber, and Zenith designs. The charming simplicity of the SU dates back to the Skinner brothers’ 1908 design with a suction chamber to regulate the air and gasoline mixing, sealed by leather bellows, and improvements in machining meant that a piston was used to provide the pressure differential by the early 1930s. This later design was patented, but not the earlier, so that when in 1958 the British Motor Corporation declined to provide the SU product they had come to own, to their competitors, a development engineer named Dennis Barbet was able to design the Stromberg carburettor using the advances in rubber technology to employ a diaphragm in place of Skinner’s leather.

The XPAG used two SU carburettors, and those variable jet instruments, and the closely related Stromberg, are considered rather than the fixed-jet Solex, Weber, and Zenith designs. The charming simplicity of the SU dates back to the Skinner brothers’ 1908 design with a suction chamber to regulate the air and gasoline mixing, sealed by leather bellows, and improvements in machining meant that a piston was used to provide the pressure differential by the early 1930s. This later design was patented, but not the earlier, so that when in 1958 the British Motor Corporation declined to provide the SU product they had come to own, to their competitors, a development engineer named Dennis Barbet was able to design the Stromberg carburettor using the advances in rubber technology to employ a diaphragm in place of Skinner’s leather.

Leaving aside the whole world of needle profiles, Ireland gives a good guide to the SU’s overhaul and maintenance, and its tuning, over several chapters. The XPAG had the hardly ideal design, of carburettors and exhaust manifold placement in close proximity, so of course the elimination of fuel leaks is emphasised. At the other extreme, the splendid isolation from any possible heat source on a cross-flow cylinder head meant that the twin SUs on your reviewer’s Riley 12/4 always indicated their correct state of tune by icing up inconveniently on cold and dark nights.

The mysteries of ignition are well covered, and suggestions are made regarding adding more advance than originally provided, in order to reduce exhaust temperature and counteract the conception that modern fuel burns hotter than “classic.” Ireland does not advocate the use of electronic ignition, pointing out that failures are unlikely to be solved as readily as on the straightforward original design. Cold, dark nights again…

Ireland provides frequent safety suggestions and “Don’t try this at home” caveats, and although the technical details may induce tie-twiddling and finger-wiggling in the reader, it must be hoped that the trusted mechanics upon whom we all rely will also read this book.

Ireland provides frequent safety suggestions and “Don’t try this at home” caveats, and although the technical details may induce tie-twiddling and finger-wiggling in the reader, it must be hoped that the trusted mechanics upon whom we all rely will also read this book.

Paper and print quality are excellent, with graphs, drawings and photographs, albeit small, but all in color, on most pages. The book will, when properly run in, lie fairly flat.

Ireland’s book began as notes, so the persnickety reader may waste effort in mentally joining passages into properly punctuated sentences. There are also the usual minor quibbles with grammar, such as singular and plural confusion: “This chapter should reduce an owner’s worries and help them be better prepared for the future.” One unfortunate typo gives us “lose” for “loose”—not the word we want in the passage about tiny SU bits!

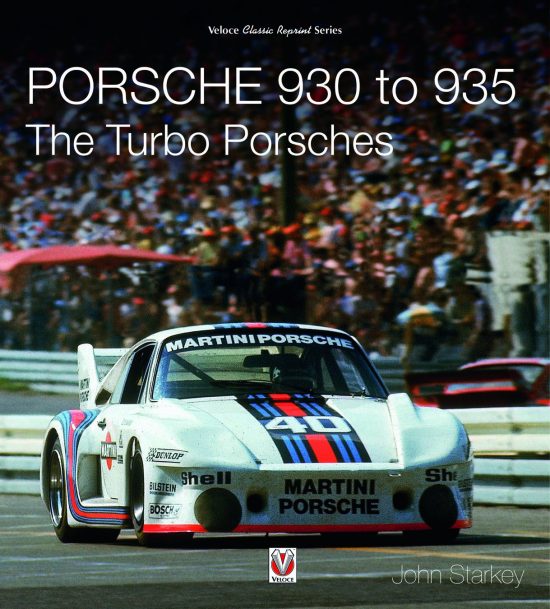

Well done, Paul Ireland and Veloce Publishing!

Copyright 2020, Tom King (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter