The Lamborghini Miura Bible

by Joe Sackey

by Joe Sackey

“Sophisticated and sleek, there’s no question that if James Bond was Italian, his car of choice would have been a Miura!”

“Bible” is such a big word, laden with promise and received with expectation, but US Miura expert Sackey’s opus is well and truly The Book (in the sense of being a definitive word) and not just because there hasn’t been another serious Miura-only book (by Coltrin & Marchet) in 30 years. Soon enough anyone who has anything Miura-related to settle will quote chapter and verse from it. In fact, the first print run sold out within four months of publication! Also, Sackey has already committed to future editions if and when “newly received wisdom” becomes available—but only after “it is properly established.” This last bit is a crucial part of Sackey’s modus operandi. For his own book he was not content with just interviewing all the principals who had anything to do with the Miura (development engineer Claudio Zampolli wrote the Foreword), he cross-checked and corroborated everything until it was “properly established” and thus fit to become gospel.

This all started 20 years ago and Sackey is certain that in his book he weeded out all the gibberish (that Lamborghini was a hands-off executive who didn’t read and only watched Westerns), myth (that Enzo Ferrari goaded him into starting his own factory), error (chassis numbers), and ambiguity (yes, there is a clause in the company’s by-laws forbidding the manufacture of racecars) of previous reports. And he doesn’t just say so, he provides the paper trail.

Built from 1966–1972 in all of 764 copies, this two-door V12 sports car ushered in the era of the high-performance mid-engined road car. Never mind that Ferruccio Lamborghini’s engineers designed it against his wishes (he preferred powerful grand tourers to thinly disguised racecars) and in their spare time. The Marcelo Gandini-designed prototype P400 that was unveiled at the 1966 Geneva show was such a hit with both public and press that it was put into production until it was replaced by the vastly different Countach. The two have certainly not aged equally well.

Though well-earned, Sackey has his opinions and, to stay with the biblical theme, a certain fire-and-brimstone approach. He chides previous scribes for being nothing but dilettante armchair enthusiasts without any meaningful seat and certainly no wrench time (he himself has owned and restored examples of all models), takes a dim view of the one-off lightweight 1969 Jota (without any mention of the Iota, development engineer Bob Wallace’s and the company’s effort to recreate the Jota), and has disdain for “privateer customized cars and replicas.” His enthusiasm for this one model does not stop him from enumerating its and its maker’s flaws and, in his own words, the book is not a “wanton glorification” of either. It should be noted that he organized, on the Miura’s 35th anniversary, the first-ever Miura Reunion (2000, Monterey) and has brokered the sales of the crown jewels in Miuradom, the one-off Miura ZN75 roadster, SV Jota #4892, and the engineer Dallara-designed first Miura chassis and engine. He is also involved with the International Lamborghini Registry and while he maintains his own private registries for cars of his interest he does not include such information here, considering it too transitory.

The focus of the book is on design/development, technical specs, model identification, chassis numbers, and works modifications. Further attention is given to equipment variations, literature and press coverage, as well as driving impressions, ownership and restoration matters, and a buyer’s guide. One short chapter, by Simon George (writer for the Supercar magazine Evowho has the distinction of having covered more miles than anyone in a Lambo), is based on an interview with production manager Paolo Stanzani but talks more about the Countach than the Miura. Rather less is said about stylist Marcello Gandini or engineer Bob Wallace nor is there any overarching context given regarding the times or the industry. (For the latter Winston Goodfellow’s Isorivolta is eminently useful.)

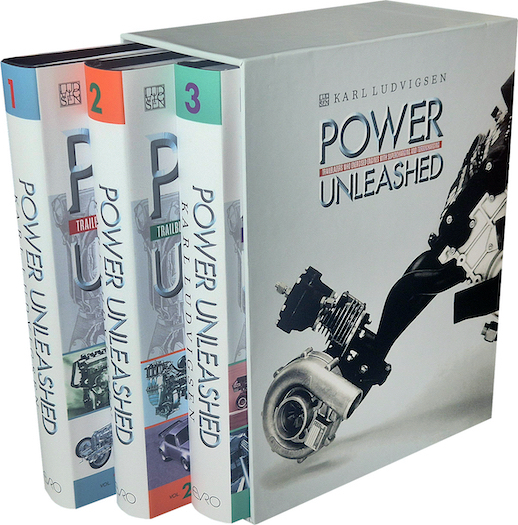

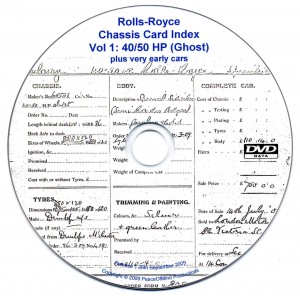

The photos, both period and modern, are plentiful and varied (although there are several that are so similar to each other as to be repetitive), of entire cars as well as close-ups of technical and trim details. Several photos are entirely new to the record, foremost the ones by Karl Ludvigsen of Miura engine production (1966) and him driving the first US-bound Miura (1967), as well as studio photography of ZN45. Complementing the photos are advertisements, technical drawings (no cutaways except for a side view of a Countach), and design sketches. The chassis number chapter is tellingly subtitled “Smoke and Mirrors” which alludes to the company’s slipshod record keeping. Sackey reproduces the company’s typed list (large enough to be legible) in toto and offers extensive commentary. There is however no comprehensive, authoritative, properly vetted chassis number list.

Shockingly, the thing at the end that calls itself “index” is nothing more than a page-long annotated alphabetical list of names of people, places, and companies but without any page references.

Sackey is also an expert on the Ferrari 288 GTO and is planning a book similar to this one about that car; same publisher.

Copyright 2010, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter