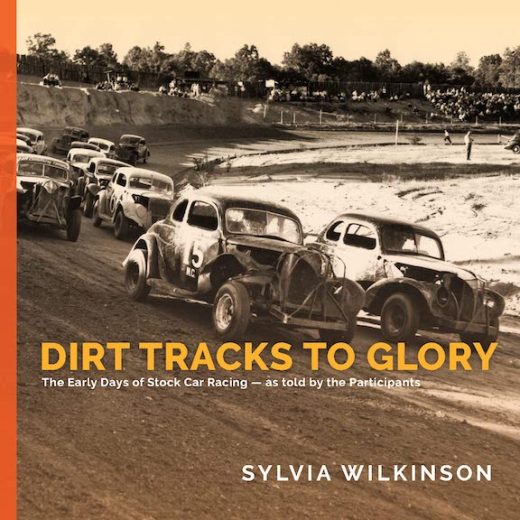

Dirt Tracks to Glory

The Early Days of Stock Car Racing As Told by the Participants

by Sylvia Jean Wilkinson

“In the final analysis, I have a book full of words—from people who spent their lives expressing and supporting themselves with machinery, roaring around in a circle or through the spiraling blacktop of the Appalachians. Richard Petty says stock car divers never think about some things, much less talk about them, unless some writer asks them to. Take fear, for example. ‘If we thought about fear,’ he said, ‘we couldn’t be race drivers. Not good ones, anyway.’”

If you don’t already know this book—it’s been around for 40 years!—the words above must strike you as refreshingly well put together, not so much the underlying sentiment but the actual words. If they do, you’re not alone: Time magazine called her “One of the most talented Southern belletrists to appear since Carson McCullers.”

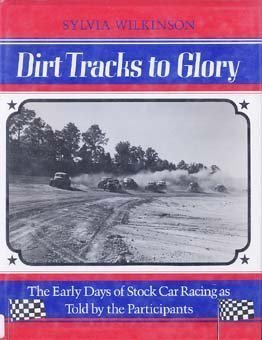

Anytime a 40-year-old book is being reissued, someone must be on to something. The book itself does not shed light on the reasons even if it does have a new Preface written just for this new version. An earlier attempt had been cancelled by the disruptions in the wake of 9/11. On a practical note, the author (b. 1940) is in her eighties and has for a long while nibbled at the thought that certain improvements and emendations would make a good book better. Likewise, that advances in printing and image manipulation might bring new life to old photos.

Anytime a 40-year-old book is being reissued, someone must be on to something. The book itself does not shed light on the reasons even if it does have a new Preface written just for this new version. An earlier attempt had been cancelled by the disruptions in the wake of 9/11. On a practical note, the author (b. 1940) is in her eighties and has for a long while nibbled at the thought that certain improvements and emendations would make a good book better. Likewise, that advances in printing and image manipulation might bring new life to old photos.

There are at least two primary reasons that had made this book good back in 1983 (written in 1981): it gathered first-person accounts from a foundational phase in US motorsports and let them stand unvarnished (edited, of course, and with some connective narrative for context), and it had been written by a woman who had carved out her own place in motorsports against the odds (primarily as a much-in-demand timer, one of maybe three people in the whole US). To appreciate the latter you’ll have to time-travel to the 1980s and recall that women in and around motorsports were still marginalized, which was actually an improvement compared to the earlier decades you’ll read about here. To quote one her interviewees, “Stock car racing is for men only. There are two groups of women in the stock car world: wives and mothers in one group, whores and race queens in the other.” Ouch. But at least the guy was letting her interview him, albeit with misgivings—twenty years earlier he had her ejected from his shop when she had come in to buy racing fuel for a friend!

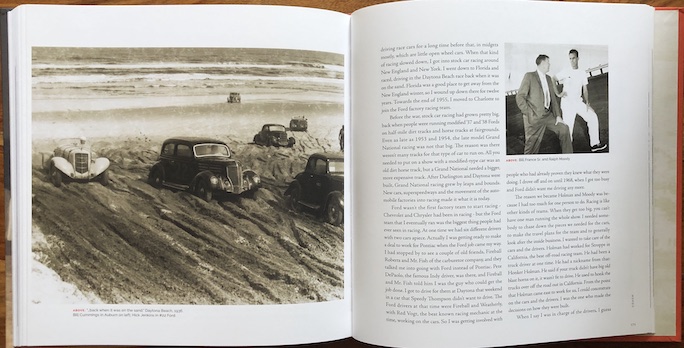

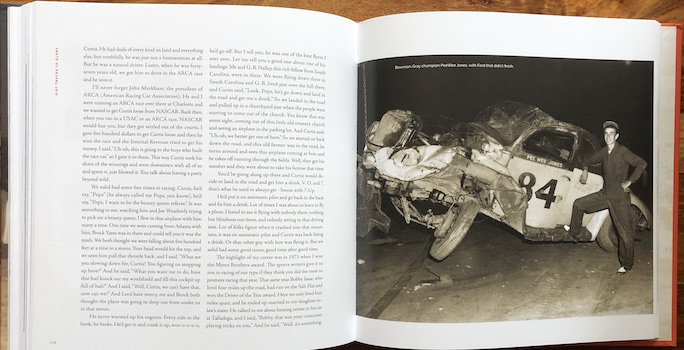

Look at those ruts! “Stock car racing came to the beach in 1936” (here Daytona), 12 years before NASCAR started.

Of the three major types of racing indigenous to these United States—stock car (NASCAR), drag (NHRA), Indy car (USAC, CART)—stock cars had the most extreme trajectory, from any old patch o’ dirt to billion-dollar glory at professional venues all over the country and then the world. Then there’s this: “All of the mystical connections between man and machine come from the streets of Monte Carlo, not the backwoods of the South or the brickyard of Indianapolis.” This, in other words, is an archly American story, and anyone interested in the origin story of US motorsports of all stripes will find here the first stirrings of a culture and of events and organizations and people that have shaped and are shaping our present.

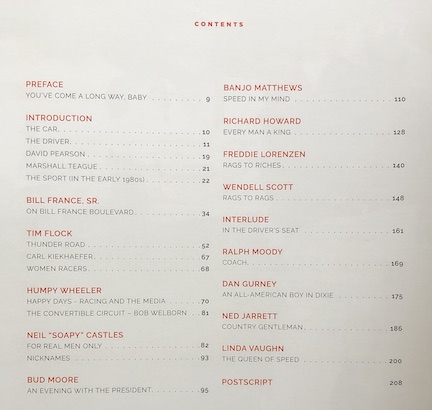

The book uncorks with a look at the Way-Way-Back of the 1930s and ‘40s and over the course of a dozen pages brings us into the 1980s. It consists of 14 chapters bearing the names of key people although everyone and everything under the sun makes an appearance (there is no Index). The last chapter is about Linda Vaughn and one wonders if it is relegated to the back for reasons of diplomacy but it is really the one to read first, not least because a woman writing about a woman requires a special acuity and point of view. There is a salient irony here because racing was decidedly hostile to women, and Wilkinson had quit her university teaching job at UNC in protest over her unequal pay as a female.

The book uncorks with a look at the Way-Way-Back of the 1930s and ‘40s and over the course of a dozen pages brings us into the 1980s. It consists of 14 chapters bearing the names of key people although everyone and everything under the sun makes an appearance (there is no Index). The last chapter is about Linda Vaughn and one wonders if it is relegated to the back for reasons of diplomacy but it is really the one to read first, not least because a woman writing about a woman requires a special acuity and point of view. There is a salient irony here because racing was decidedly hostile to women, and Wilkinson had quit her university teaching job at UNC in protest over her unequal pay as a female.

The chapter title is funny/clever, “Rags to Rags,” but nothing about the story of African American driver Wendell Scott is funny. Would you believe they had “white” and “black” ambulances in his day? If you watched the documentary “Greased Lightning” and think you got a handle on his life, read his own words here.

Wilkinson’s MO was to “let everyone just talk.” This means, for instance, that Bill France Sr. will simply not mention the bootleg side of the NASCAR story to which his name is indelibly attached. Yes, they, and mostly she, dispense plenty of facts and historical data points but this is first and foremost an oral history with the goal of capturing original—and usually not at all politically correct—reminiscences. It has to be remembered that at the time of the book’s first publication some of these events were already decades in the past and that many of those interviewed were already old. Alas, some who had not made it into the first edition and were supposed to be in the expanded new one had in fact died by then.

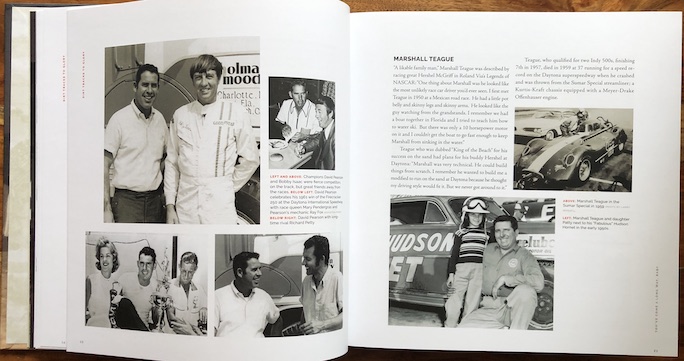

Another case of funny wordsmithing, in this case by NASCAR’s longest-lasting driver, Hall of Famer (Class of 2023) Hershel Eldridge McGriff, who describes Marshall Teague as “the most unlikely race car driver you’d ever seen . . . he had a little pot belly and skinny legs and skinny arms. He looked like the guy watching from the grandstands.”

It is of no small matter that Wilkinson is herself a Southerner, as are so many of the people in her book, one notable exception being New York-born California hot-rodder Dan Gurney. When she relates her interviewees’ attitudes about north and south, which permeate their whole outlook on and approach to life, it is not as a geographical reference but a cultural divide. Her original publisher, Algonquin Books, founded by her erstwhile M.F.A. adviser Louis D. Rubin who had a great effect on her fiction writing career, saw itself as a specifically Southern publisher and had brought this topic to her because they knew of her passion for racing but also her chops as a novelist. This was her second of now three motorsports books, after The Stainless Steel Carrot: An Auto Racing Odyssey (1973, Houghton Mifflin; reissued by Brown Fox Books in 2012 and even today NOS copies can still be found). That book had come on the heels of three successful novels, the first draft (of eleven) of the first one she had started at the tender age of 12 in her seventh-grade school notebook! She has some two dozen books under her belt by now, more than half of them for the Young Adult market and with automotive themes. Read them all and be the better for it!

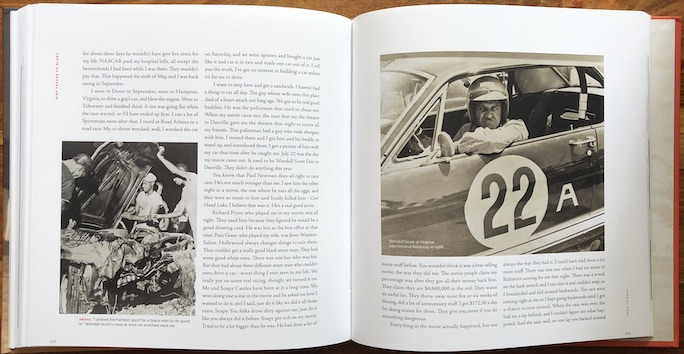

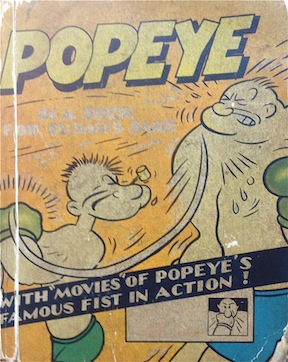

“PeeWee Jones with Ford that didn’t finish.” Well, he seems all right—and look at those gleaming shoes!

Kudos to Racemaker Press’ chief Joe Freemann who had known this book since it first came out for bringing it back for another round, and at such an astonishing low price. If you have the old one, know that this new one has corrections to some of the photo captions; some additional writing (including “stage directions” for those readers to whom 1983 is ancient and unrelatably distant); a number of new photos, partly because she had a bunch that had never made it into the first edition and partly because a third of the original photos went MIA after Algonquin Books was sold to a big New York publisher; some additional text that had been deemed “unsuitable” back in the day (but found its way into her sixth novel, On the Seventh Day); plus a few bits culled from her later writings for magazines. And, just to say it again, fine digital work on the old photos that really bring out detail that the same photo in the first edition just did not reveal.

So, all around a mighty fine book, “guaran-damn-teed” as one of Wilkinson’s protagonists would say. Her original taped interviews still exist and have been digitized, hopefully to be preserved in an appropriate archive.

Copyright 2023, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter