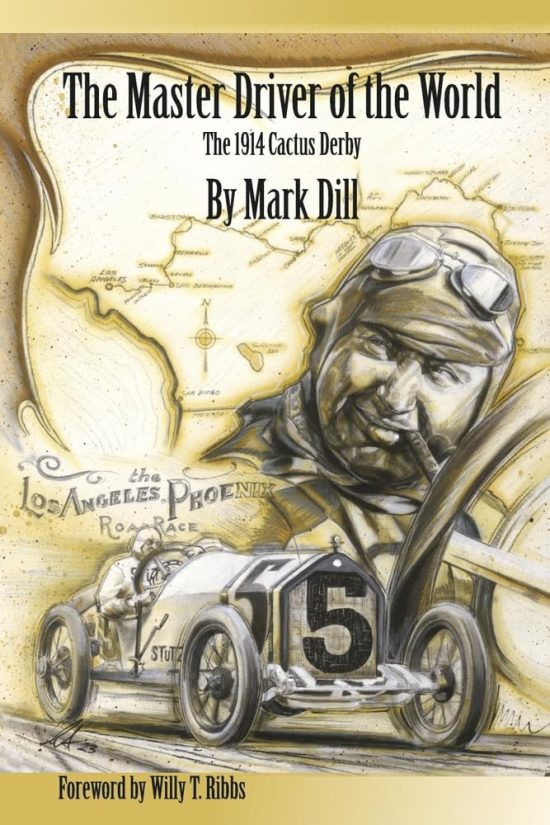

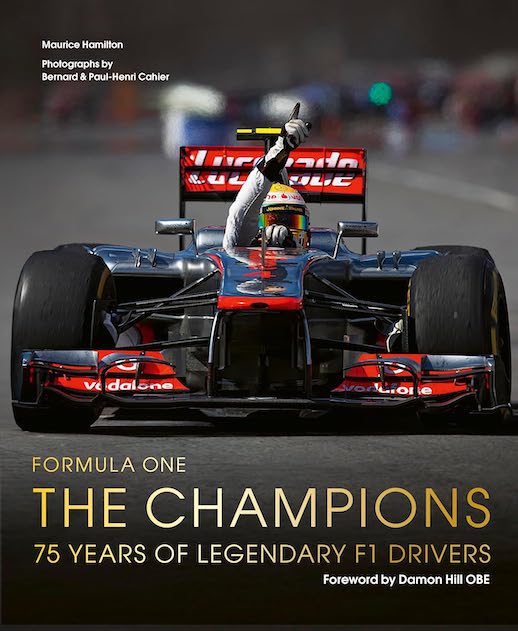

The Master Driver of the World, The 1914 Cactus Derby

by Mark G. Dill

by Mark G. Dill

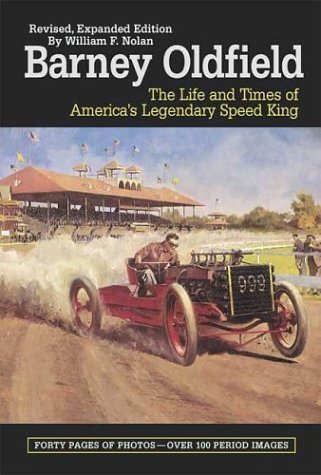

Until Mark Dill wrote and published Master Driver of the World focusing on the 1914 Cactus Derby it was William F. Nolan’s biography Barney Oldfield, The Life and Times of America’s Legendary Speed King that had been the single main resource.

Nolan’s book was first published in 1961 by G.P. Putnam’s Sons. After the millennium this prolific author (being credited with 70 books qualifies him as prolific, right?) decided to rewrite, and Brown Fox Books published it in 2002. Now there’s a new writer adding his views on Barney Oldfield. Although Dill uses the 1914 Cactus Derby competition as his book’s raison d’être, interspersed are chapters that flash back to prior events and aspects of Oldfield’s life.

Publisher BookBaby categorizes The Master Driver of the World as a history. However I found myself wondering whether it might be more accurate to describe it similarly to author Dill’s first book that was about the creation of Indianapolis’ Speedway, as a work of historical fiction. As Dill expressed it to the writer of one of the prefaces to that first book, “I’ve read so much about these guys I really feel I can get into their heads.” So he crafts dialog and with Oldfield he characterizes this master showman’s speech and some of his attitudes as sometimes a bit crude and rough.

Then too I noted some differences between the Nolan biography of Oldfield and Dill’s recounting of certain instances. One concerns how Oldfield’s riding mechanic George Hill badly injured one of his hands. Nolan described it happening after an engine backfire set off an underhood fire with “Hill attempt[ing] to free the fire extinguisher from its bracket on the cockpit wall, slashed his right hand in the process.” Dill, on the other hand, writes the injury occurred as “the mud-coated Stutz sometimes leaped as it bounded over the craggy trail.” Hill grabbed at something to hold onto in order not to be thrown out of the car and in so doing sliced his hand.

Then too I noted some differences between the Nolan biography of Oldfield and Dill’s recounting of certain instances. One concerns how Oldfield’s riding mechanic George Hill badly injured one of his hands. Nolan described it happening after an engine backfire set off an underhood fire with “Hill attempt[ing] to free the fire extinguisher from its bracket on the cockpit wall, slashed his right hand in the process.” Dill, on the other hand, writes the injury occurred as “the mud-coated Stutz sometimes leaped as it bounded over the craggy trail.” Hill grabbed at something to hold onto in order not to be thrown out of the car and in so doing sliced his hand.

Another difference is how the Howdy’s—the club of Los Angeles businessmen and boosters that followed the action from the comfort of a chartered railroad train (the route ran alongside the train tracks) dubbed the Howdy Special—are characterized. Nolan’s description has them wholly and totally supportive of Oldfield and Hill. He noted they included race officials and even a masseuse in their number. It was the latter’s job to ease the battering Barney and Hill’s bodies endured on each day’s run.

In contrast, Dill has some of the Howdy’s number taunting Oldfield and many placing bets with odds as great as 10:1 against his winning. A number of them even did their best to tease and encourage Barney to drink during the race, plying him with challenges and invites to toss back a few drinks with them, a form of sabotage which would serve to blunt his competitive edge and put him off his game.

Both authors had access to period newspaper reports and other documents. Moreover, Dill has built and maintains an extensive online archive of pre-1920 auto racing history with still other sources/resources on his other website and at www.MarkGDill.com

Unfortunately for us, Nolan (1928–2021) can no longer speak for himself. It would no doubt be a fascinating conversation if Dill and Nolan could compare notes. It is certainly a conversation your commentator would have been most interested in hearing.

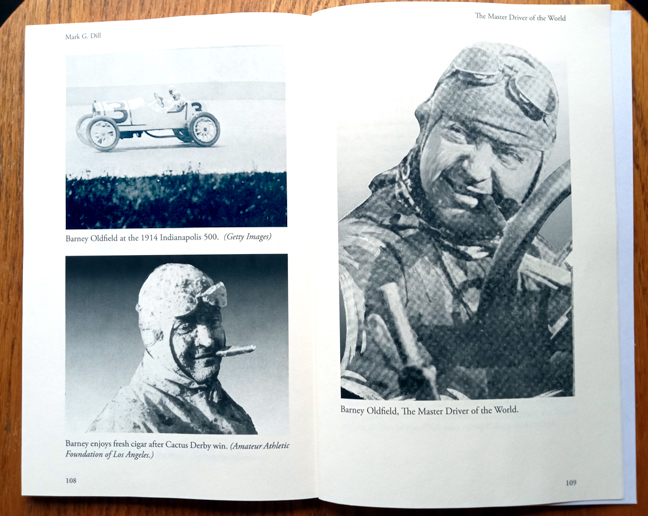

Nolan’s book contains forty-some pages of just images—something over 100 of them—whereas Dill’s book is all narrative until the final half dozen pages on which are reproduced a dozen or so period images. One of those page pairs is offered here. The real service Dill’s book contributes is its day-by-day, practically mile-by-mile, description of those 1914 days along with the challenges ma nature presented to the racers as well as the challenges of competing against one another that is ever and always a factor in any race.

Even taking into consideration all the racing action told of, Dill’s concluding chapter is perhaps the best one overall. It features a conversation between Barney Oldfield and Los Angeles Times reporter Al Waddell over a rare Porterhouse steak as they rode “The Howdy Train back to Los Angeles” for Waddell had told Barney he was planning a lengthy full profile on The Master Driver of the World because, “I figure you’re at a point in your career where it is time to reflect and assess. I want to hear your thoughts on how you got to this moment. And where you’re going.”

The artwork on Dill’s book cover drew my attention so I sought out more about its creator for his name, Alex Wakefield, was unfamiliar to me. The search was rewarded with learning that Wakefield had been artistically inclined since childhood. Art school polished his skills and soon he was hired by the Indianapolis Motor Speedway as a graphic designer, a dream position for someone like Wakefield with his appreciation for history and motorsport enthusiasm. When he left the Speedway’s employ, he concentrated on developing his fine art and the market for it. This book’s cover provides one example of his talents.

You can accompany Barney Oldfield and George Hill on their fast transit of the 671 miles of unforgiving terrain of the California and Arizona deserts on the 1914 Los Angeles to Phoenix Desert Classic Road Race in this fast-paced and fresh look at Barney Oldfield.

Copyright 2024 Helen V Hutchings, SAH (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

Would like to thank my friends Mark Dill and the late William F. Nolan for keeping the legacy of my Great Uncle Barney Oldfield, Master Driver of the World & America’s Legendary Speed King, alive. Was honored to be of help on both books. American Automotive Racing History at its best!