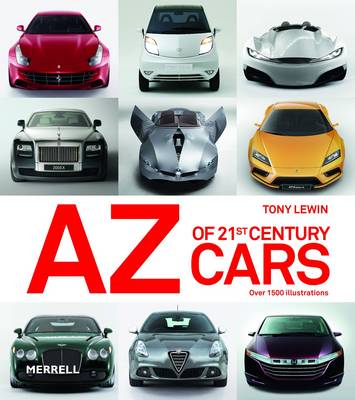

The A-Z of 21st-Century Cars

by Tony Lewin

by Tony Lewin

“Whether in motion or parked on the street, cars are the most visible form of design in our public spaces: their shapes are an important ingredient in our visual environment.”

Not to be mistaken for an encyclopedia-like blow-by-blow/model-by-model compendium of automobiles, this book looks at people, firms, and models that “changed the course of car design.”

Naturally, seeing the words “A–Z” conditions the reader to expect an exhaustive “Abarth to Zagato” sort of compilation. This book’s narrower focus on car design is no surprise considering Lewin’s previous books How to Design Cars Like a Pro and the annual Car Design Yearbook series (started in 2002) he writes with Stephen Newbury. In the larger scheme of things he’s been writing about cars and the car industry for 30 years and is a former editor of the British magazine What Car? (the self-acclaimed “biggest and best car buyer’s guide”) and launched Financial Times Automotive World.

Here he offers some 300 entries about those cars and designers “that altered the outlook and the expectations of the man or woman in the street; that inspired interest where previously there was none.” While these are timeless concepts the entries here pertain to mostly recent decades. As with all books casting such a wide net, the matter of selection rears its head. No matter how objective the criteria, the author’s choices are not only subjective but are further guided by the fact that a book has to be limited to a certain size and sell at a certain price. So, embrace what it does include and don’t argue about what it does not.

In a very well articulated Introduction Lewin paints a picture of the car as different from any other consumer product in terms of how a “highly design-conscious society” reacts to it. How automotive brands are perceived, how brands create and perpetuate an image, and the role of the designer in this process are the lines of inquiry that shape this book. All this may sound terribly abstract but Lewin shows the reader that it isn’t. And if that doesn’t light your fire consider that the book contains some 1500 images and even random rifling through the pages on a whim will entertain you for hours. This being a European publication of global scope, the entertainment—and envy—quotient will be especially high for US readers who will have occasion to groan yet again at the sight of mouthwatering, DOT-unencumbered examples of automotive finery that will never make it to these shores.

Some noteworthy thought went into the organization of the contents: the three main categories—designers/studios, marques, models—each have their own Table of Contents and are assigned separate colors (green, blue, red respectively). Since the book is set up in alphabetical order, not by category, the color-coding in the form of a colored stripe across the width of the page gives a quick visual cue as to what category you’re reading about. Each letter of the alphabet also has its own Table of Contents.

For each entry the main text is augmented with sidebars presenting (depending on category) biographical bits (career highlights, key designs), principal models, car specs (including—what novelty—emissions output in g/km), or timeline of company history. What is said in these descriptions is in the service of the aforementioned premise/s; in other words design-focused and not a general, “nuanced” history. And therein lie complications. We do not like to make unsubstantiated claims and so offer an example: the “boxy” design of the Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow (p. 434) is described as “lacking the aristocratic poise” of its predecessor and thus detrimental to esthetics. The unsuspecting reader would thus conclude that this model must be unsatisfactory—because the author omits to mention that this “deficiency” did not stop paying customers from voting with their wallets and making this model the highest-selling Rolls-Royce ever. Ever. And the supreme irony here is that Lewin knows this because in his How to Design Cars book he includes that very model in the “50 Landmark Designs” chapter.

Even on the mere factual level there are weaknesses; we will, again, give one representative example: the same incident—the 1970s bankruptcy of the Rolls-Royce Group—is listed under both the “Rolls-Royce” (p. 434) and the “Bentley” (p. 60) brands but each time with a different year. Now, no one is saying that one author should, or even could, know everything about everything—but that’s why you hire a good editor and fact checker.

Among the many nice touches are lists of which brands belong to which corporate parent (current as of May 2011), and independent makes and studios (which could have been better still if the country were listed). There is a useful glossary of design terms complied by one the big names on the British design scene, Coventry University. Units of measure are given in metric and Imperial form. In lieu of an Index the text is extensively cross-referenced. Do be aware that the type is microscopically small (5 pts). The photos are largely stock but interesting nonetheless.

So, to boil it down to one pithy final thought: a pretty book, with a good idea behind it, making useful and interesting connections on the macro level but suspect on the micro detail level.

Copyright 2011, Charly Baumann (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter