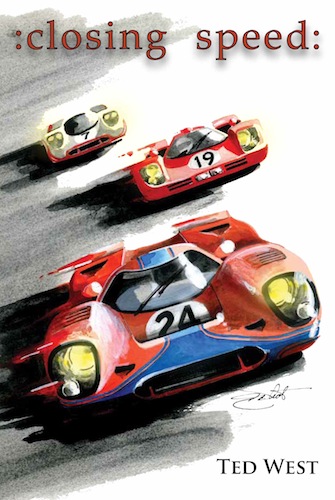

Closing Speed

by Ted West

by Ted West

First things first: start this book at the back.

Without reading the back cover you wouldn’t know the time and circumstances, namely that the author traveled to Europe as a racing reporter in 1970. Assignment: cover the World Manufacturers Championship for three months. And it will be good to know that the author was there and that this is on some level the basis of the book, lest you end up wondering what the point is of telling a story that so closely mimicks actual events that the reader will often find it difficult to tell reality from fiction.

If you don’t know racing history you’ll read this book like you would any novel. It grabs you or it doesn’t. No further comment. Oh, the cover artwork by Michael Jekot (who did the SpeedReaders logo!) is fabulous (and available separately as a poster).

If you do know about racing in that era, your brain will, without even making a conscious effort, flood your mind with facts and stats and images and half-remembered snippets of this and that. If you’ve read, say, The Speed Merchants, which covers exactly these events at exactly this time you’ll immediately see the parallels between real life and this part-docudrama. This helps inasmuch as it provides texture, and it hinders inasmuch as you knowing, for instance, that John Wyer’s Gulf Oil cars were orange and blue gets in the way when the author tells you that his protagonist Raymond Beacom’s Carnelian Oil cars are bright tangerine with navy-blue. If the author wants to take literary liberties, then why cut it so close? (Lack of imagination?) This is just one of innumerable examples. Muddying the waters further, and for reasons undisclosed, West mixes his fictitious (but so obviously recognizable) proper names with real-life ones.

It starts out promising enough. Fast cars, a mysterious woman in black—the ingredients for high drama are there. But then, no dramatic arch, no development of theme or character. The story just . . . is. The cars remain fast, on page 80—the first time something actually happens that seems to have anything to do with this particular story—one finally crashes, quelle surprise. The woman in black turns out to be a herring, with no discernible impact as a building block in the story. What themes there are revolve around unrequited love (with an entirely gratuitous soft-porn, ahem, climax that, if this were a movie filmed as written, would have garnered an X rating), the dangers of egotism, the need for speed. At no point are there insights—certainly not new ones—into the human condition or the meaning of life unless we count, on page 142, the psychological need of the racer to race (“the longer I’m in it the less I know what it means”) or p. 171—if we make it that far—the pensive German race driver’s ruminations on “the value of waiting.”

(We interrupt this broadcast for a bit of stage direction)

Reviewing a novel is akin to describing wine. The words are there; you know them and I know them. And still we both in all likelihood conjure up different images when we try to picture in our minds a “sappy midpalate without being cloying, hints of underbrush backed by tightly woven layers of roasted fig held together by a tangy iron note, good latent drive.” Say again? So how does it taste?? In other words, the normal parameters for reviewing nonfiction books don’t apply here. There is one tool in the ole tool chest, though. It’s sharp and cuts to the quick: literary criticism.

(Resume play)

For our purposes, let’s use literary criticism in the sense of “an interpretive strategy that focuses on the particularly literary qualities of a text, an author’s style, vocabulary, etc.” In no particular order: Most of the time the protagonists’ clothing is described in great detail. Detail so great that one surmises it must be a critical factor in the story. But it isn’t. Unless someone’s “oatmeal cable-stitch wool sweater” (p. 56) turns out to be the murder weapon (don’t get your hopes up; there isn’t one), what does this sort of detail add to advancing the story? When a paragraph starts in France and ends in Switzerland (p. 82), all the while using similar French place names but without clearly delineating the geography, is not the reader’s ability to follow along affected? Is “lubricous” (p. 49) a show-off word or critical to the storytelling? These are objective criteria worth examining; we won’t even mention subjective ones, such as the excessive use of cliches (try making it through the first 20 pages without bursting a blood vessel).

Ask yourself this: if you can pick up a novel that is new to you and begin reading the story randomly anywhere in the book without ever getting a sense of being lost in circumstances and characters you don’t know, is that a novel you’re curious enough about to devote precious hours of your life to reading from the beginning?

Copyright 2011, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter