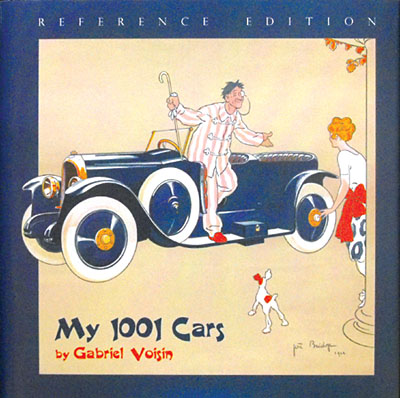

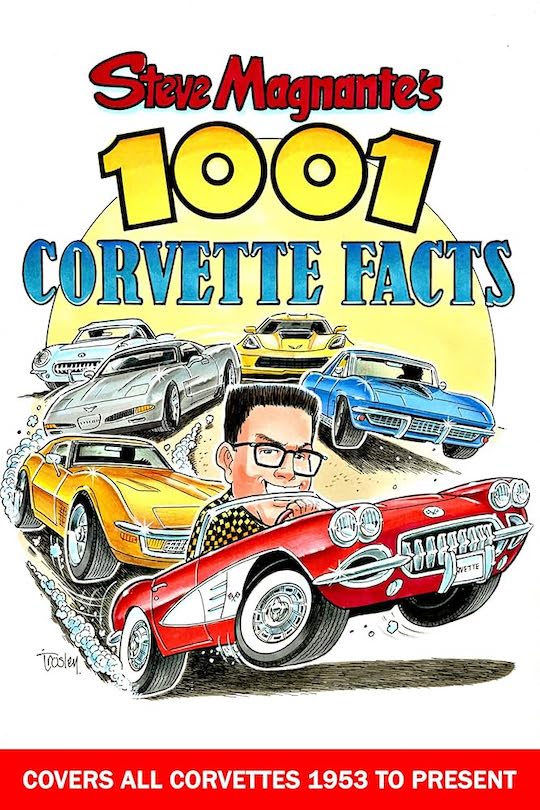

My 1001 Cars, The Reference Edition

The best books need the shortest review: Buy it. Right away.

“A practical man who couldn’t look at a functional object without trying to devise a better way of fulfilling its purpose. A man with no head for business, but who worked as hard as he played. A man unmotivated by money, but who spent it with panache.”

What, you’re still not itching to read this book??

Alright then. Say it’s 1927 and you’re looking for a new car. One of them French motors takes your fancy—a Voisin. You order the catalog. You flinch. Repeatedly. “The purchaser of a motorcar,” it says at one point, “always reminds us of a child wanting to buy a toy.” If you’re a rational sort of person—the only kind arch-rationalist Gabriel Voisin deems worthy of his products—you’ll agree with the sentiment, even if you bristle at the words, when it says elsewhere “Publicity that does not give facts is a despicable imbecility and a waste of your time.” Harsh, n’est ce pas? Just wait until you actually bought the car and read the manual. On page after page it leaves no doubt that you, the hopelessly incompetent consumer, will surely find all manner of ways to ruin Voisin’s perfect machine only to then blame the maker.

Voisin’s view of his fellow man did not improve over time. The house in which he wrote in his eighties this memoir was surrounded by signs warning trespassers that advancing further would set off discharges of pièges à feu—gunpowder, often laced with coarse salt to really prick the skin (lead shot being frowned upon by the authorities). If this makes you see Voisin as a bitter old curmudgeon, you’d be wrong. Grossly oversimplified, he saw himself as the smart man in a stupid world. And smart he was; you don’t have to take his word for it. By any objective measure, Gabriel Voisin (b. 1880) was a giant among men, an innovator of the first order, an original thinker. And a man who did not get his due, especially in aviation matters, the first of his three lives and the one he cared about the most.

In this book, though, you do have to take his word for what it says about him—it is, after all, an autobiography. Unlike the original version, which only ever existed in French, this new one benefited from the ministrations of an editor, or, rather, commentator. An “editor” would have probably helped Voisin straighten out his often ponderous way of expressing himself but Reg Winstone, who even in his English translation purposely tried to maintain Voisin’s voice, draws on his decades of immersion into all things Voisin to offer critical insights, context, and even corrections to passages where Voisin’s own memories failed him or where he intentionally fudged the record. As a longstanding member of Les Amis de Gabriel Voisin, the keeper of the flame, Winstone is a proper authority on the subject in particular and French engineering activities in general. And he has a way with words, tossing off with ease such uniquely British, dry, understated witticisms as referring to Voisin as “a robustly opinionated character.” Elegant, clever, a joy to roll around in your head.

All of the above should suffice to convey that Voisin was a complex character and that his story, warts and all, is commensurately rich in color and detail. From the inner workings of a gearbox to gossip to interactions with his fellow man—and especially woman—he tells his story with verve, possibly even joy, which is all the more surprising considering that he really didn’t want to write his memoirs at all.

This book is actually the second of two volumes, covering 1917 to the 1960s. First published in 1962 in French as Mes mille et une voitures (ISBN-13: 978-2360590070, Edition de La Table Ronde. Re-issued in 2010 by Editions du Palmier) it was never translated into other languages. As you would gather from the title, it deals predominantly with motorcars, the one activity Voisin is best remembered for today but the very one he cared for the least. Aeronautics was his first professional endeavor and the field in which he truly advanced, no, pioneered the state of the art. That, and his childhood, were the topic of volume 1, Mes 10,000 cerfs volants (1960), published in English by Putnam in 1963 as Men, Women and 10,000 Kites. He also wrote, and illustrated himself, a book of hunting recollections (Nos étonnantes chasses, 1963) and there exists a considerable body of as yet unpublished philosophical musings about life and the future.

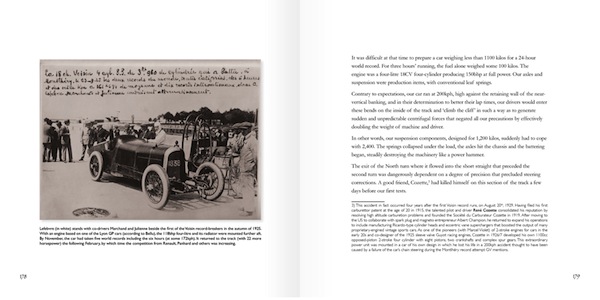

The early versions of his memoirs were Spartan: no illustrations, no apparatus, no fancy presentation. This is yet another aspect in which Winstone’s “Reference Edition” shines. It has over 150 extensively captioned period illustrations of which many are new to the record, generous layout and properly thought-out typesetting, footnotes (on the same page on which they are called out, merci bien), and a list of 1908–66 patents. Two Appendices carried over from the original offer Voisin’s thoughts on safety, traffic and weight, and modern car design. All this on good paper, properly printed and bound as a hardcover—and indexed!

On every count and without reservation, this a desirable book and beautiful to behold. It is true of many people, and most certainly of Voisin, that to understand their work you have to get to know the person behind it. It is hard to think of a reader, no matter his interests, who would not find something engaging in this book.

A word about the publisher. Faustroll Books is a new enterprise whose mission is to “explore the technology of early 20th century France in terms of its wider sociocultural context.” Their currently three titles all deal with Gabriel Voisin. Faustroll describes itself as “determined to be an authoritative imprint [and therefore] meticulous about the accuracy of what we publish.” Judging by just this book they are clearly a publisher to watch and set aside shelf space for!

Copyright 2012, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

Thank you for sending me your more than generous critique of My 1001 Cars.

I consider myself fortunate that the book has received generally very positive reviews in the specialist press, but yours is by far the most elegantly crafted, the wittiest and the best informed. Your knowledge of the subject matter shines through, and I’d find it a delight to read even if I had nothing to do with its subject.

With sincere thanks and best wishes,

Reg