45 RPM, A Visual History of the Seven-Inch Record

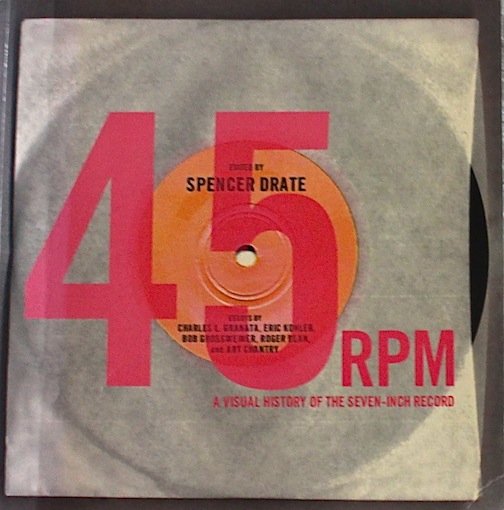

Spencer Drate is a graphic designer and creative director of Drate/Salavetz. Some of his company’s clients had included Billy Joel, Talking Heads, Lou Reed, Mick Taylor, and Sir Paul McCartney. He has the chops for this book. On the front cover, floating underneath the red bold title we find an image of a 45 RPM record, life-sized, in a translucent glassine sleeve. Additional information, the editor and the contributors, is formatted as the title, artist and recording information on the disc illustration. In the USA we are used to seeing 45s with the 1.6“ center hole, but although a “punch out” is seen for this, the illustration shows the record with the much smaller LP-sized spindle opening. Drate demonstrably shows his talent in the precision in which he uses a small shadow to create a clever illusion. Each time you look at the cover, you must remind yourself that it is perfectly flat and that despite what your eye tells you, it is not possible to insert the tip of your fingernail into the spindle opening. The rendering of the transparency and texture of the sleeve also works well. The back cover shows the sleeved record’s B-side with the blurb, in large red font as an overlay. Odd, though, that the B-side label is blank. The ubiquitous striped ISBN and price label is centered below the image of the disk’s label proving that Drate did the best that he could with this necessary but inconvenient design element. The spine, with the author and title, shows a mid-slice of a 45, the grooves looking somewhat worn. Eye-catching, then, is the design, and as you leaf through inside the book, you find the graphics smart throughout.

The layout for the main introduction and for the introductory chapter essays freely uses white space, allowing the text to breathe. The very first page is an abstract illustration of a vinyl record (and this image pops up near the end of the book again, another design touch worth the notice), the source of the image on the spine of the book. The introduction by Charles L. Granata, set in red font, is informative, a history of the various sizes and speeds of disc recordings. Granata tells how RCA tried to win the size/speed war by offering albums as a set of 7-inch 45 RPM records, their sides programmed and numbered so that the listener could stack them on a large spindle in playing order; and how, because of the inherent deficiency of this arrangement, it was soon abandoned. For nostalgic car buffs, it is fun to read of the attempts made to design a record changer/turntable for one’s driving pleasure. And Granata states the obvious—that LPs were well-suited for symphonies (they also favor extended jazz compositions and concept albums) while the 45 RPM seven-inch discs were perfect for the pop hit single. The 45 was introduced in 1949 and rock-n-roll happened not long after, a heavenly match if ever there was one.

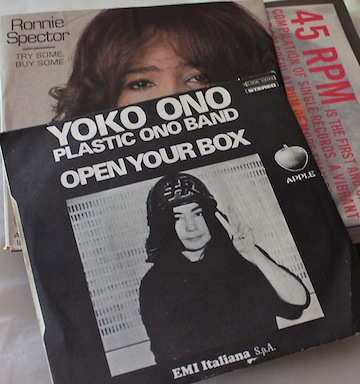

For the most part, the book is not paginated. The “discography” lists the sleeves in order, giving the artist, the song title, the record label, the release date and, when known, the illustrator, designer and/or photographer. Chapters are by decades, the 1950s through the 1990s, and each is introduced by a graphic designer, thus adding weight to the book’s concept and theme. Art Chantry (appropriately named), for example, introduces the 1990s, Chantry being “the subversive design genius behind countless independent 45s.” These introductory essays are short and to the point and this emphasizes that the book’s raison d’être is the reproduction of 45 RPM record picture-sleeves, “prized objects of fascination” to use Granata’s words. The book delivers: Reproduced are over 200 photographs of the actual sleeves in their actual size, and the progression of the graphic styles over time just may make many a collector covet each and every one.

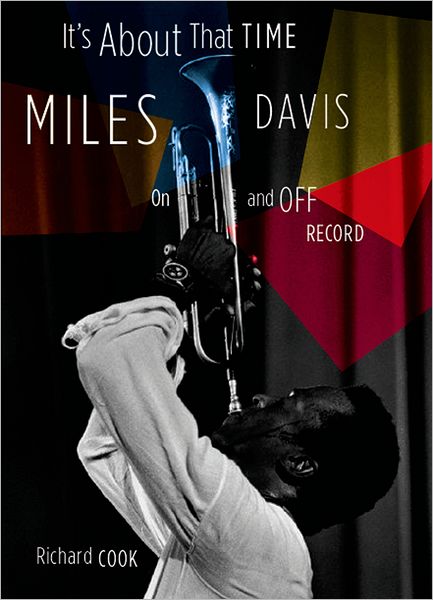

Ah, the sweet and tart savors of collecting! If there is a set of something of roughly the same size and the same intention, a baseball card for example, collectors weep openly with pleasure to find a complete set—but always, always, there are always those few oddments, hard-to-find pieces, to compel a rabid collector, perhaps at a certain age and with a certain commitment to life and values, to gladly hand over large money for a rare and sanctified object d’art, for the pride of possession, as to fill, say, even the blocked hole in a Blue Whitman Coin Folder. So it is with the Picture Sleeve, this by-now archaic form of lithography, a talisman more than a usable object. Collect them all! But that, even to the richest and most hardcore collector, money-no-object, would be an absurd impossibility. Millions of them exist. But narrow it down: Select a set of the hand-drawn jazz art from the 1950s or, on the other end, the in-your-face late 1990s artwork from such groups as The Fatal Flying Guillotines and Tsunamis. Or go into the cherished world of the 1960s: The Stones, The Temptations along with the lesser-knowns . And all of this leads off into a philosophical cul-de-sac: Is there a diminishing return through time as the importance of these objects and the artists and the eras they represent decline, fade and eventually become but a footnote to a footnote? Through this dissemination of millions—billions?—of record sleeves, these adverts and come-ons for the vinyl inside,

Ah, the sweet and tart savors of collecting! If there is a set of something of roughly the same size and the same intention, a baseball card for example, collectors weep openly with pleasure to find a complete set—but always, always, there are always those few oddments, hard-to-find pieces, to compel a rabid collector, perhaps at a certain age and with a certain commitment to life and values, to gladly hand over large money for a rare and sanctified object d’art, for the pride of possession, as to fill, say, even the blocked hole in a Blue Whitman Coin Folder. So it is with the Picture Sleeve, this by-now archaic form of lithography, a talisman more than a usable object. Collect them all! But that, even to the richest and most hardcore collector, money-no-object, would be an absurd impossibility. Millions of them exist. But narrow it down: Select a set of the hand-drawn jazz art from the 1950s or, on the other end, the in-your-face late 1990s artwork from such groups as The Fatal Flying Guillotines and Tsunamis. Or go into the cherished world of the 1960s: The Stones, The Temptations along with the lesser-knowns . And all of this leads off into a philosophical cul-de-sac: Is there a diminishing return through time as the importance of these objects and the artists and the eras they represent decline, fade and eventually become but a footnote to a footnote? Through this dissemination of millions—billions?—of record sleeves, these adverts and come-ons for the vinyl inside,  what of the discerning collector?: “I own one of the very few Picasso sleeves—made for the obscure Bell label!” or “Check out my very eccentric, very desirable The Rolling Stones promotional cover!” Or the more casual collector: “Yes, I have a handful of Beatles sleeves—and is that a cigarette between Sir Paul’s fingers on “I’m Happy Just to Dance With You”? But how long will the importance and status of these hold? Will Picasso outlive the Beatles, or could it flip the other way?

what of the discerning collector?: “I own one of the very few Picasso sleeves—made for the obscure Bell label!” or “Check out my very eccentric, very desirable The Rolling Stones promotional cover!” Or the more casual collector: “Yes, I have a handful of Beatles sleeves—and is that a cigarette between Sir Paul’s fingers on “I’m Happy Just to Dance With You”? But how long will the importance and status of these hold? Will Picasso outlive the Beatles, or could it flip the other way?

Which brings us to the heart of the matter. These fleeing images—the book here reviewed is over ten years old now! And here at Speedreaders.info we are only now getting around to it. But think: In another two years or even less the distinction between the now overdue and the historic archive will be meaningless. Time travels that fast and revs up exponentially as we go. For those of you over 60, just think if someone told you back when you were 17 that a universe of online, texted material would be available to anyone with a laptop, smartphone, or computer. Implausible Science Fiction. Or for those of you from the future, a little plug-insert behind your ear that lets you do your texting, scrolling, researching etc. whilst you look over your collection of mid-twentieth century artifacts, Picture Sleeves among them. We float in the Universal Cloud and we, you the reader and I the reviewer, along with millions of others, we float uninhibited through this Cloud; we pour through all of this wonderful stuff, these hundreds of elegant Speedreaders reviews for example—but note: These reviews are not hardcopies, they are made up of digital font and pixels. Some younger collectors understand this intuitively and are no doubt assembling digital collections of one sort or another, but others, getting back on track, will gather objects, these often beloved 45 RPM Picture Sleeves being ripe for such an assemblage.

No wonder Princeton Architectural Press offered up its imprimatur to something some may consider—wrongfully—beneath the notice of the aesthete: Picture Sleeves featuring line-drawings of Sinatra and Clooney; that heavenly sneer of Elvis Presley (and when was the last time you saw Elvis on a supermarket-tabloid?); pretty boys like Fabian—who, eventually went on to play in a handful of movies, The Longest Day among them; the iconic 1960s and 1970s overripe with The Beatles; the Indie Bands with their post-pop-art sensibilties—all playing, as it were, at forty-five revolutions per minute. And as I am winding my way through this labyrinth—as we live in this post-digital age, or nearly so, a twisting, turning tunnel absorbs facts and images and pixels as it moves speedily along and these detours, digressions, asides and indirections seem almost mandatory. And in this I hope to find my way back to the thesis: The images in this book evoke a manifest time and a place, a feeling and an aesthetic now long gone—and to those of you under thirty you may find all of this nearly incomprehensible, but to others with an older sensibility, the offerings are wonderful: pen-and-ink, ink-washed images of Nat King Cole or Frank Sinatra; punk art, hardcore to shock and surprise, but homey and safe somehow nonetheless; the Rolling-Stones; Manfred Mann. And when it gets down to this level: Who in, say, 2045 will have any real knowledge of Manfred Mann? Even then the Beatles will be known for their influence, their claim to fame as the absolute Most Popular Group ever; but in 2045, how many, besides a small covey of scholars rummaging through the lumber of the Department of Cultural Studies, will ever have really listened to the White Album complete?

Here is what I am getting at and here is the heart of Drate’s 45 RPM: This book is important because it freezes an era succinctly, offers more than just an entrée of examples. How about the Spock cover for “F**k You Spaceman”—insouciance in spades? Especially for us oldsters this is a very nice book to pick up and thumb through. You might feel 21 again, young when the Beatles were still new, but even now the Yardbirds seem now but a footnote on some remote Master’s Thesis about the 20th century from the point of view of the mid-21st—and how many of YOU, oh, Speedreaders.info readers, have listened to a Yardbirds song in decades? Quick! Name one of the stars from this stellar group!* What I am discussing, finally, is this wonderful need of collectors to gather these cultural-artifacts, combine, collate and reproduce them in a book for all to share—and how many 45 Picture Sleeves can be found on the Internet today, a dozen years after the publication of 45 RPM? But we older folks like the feel and the texture of the book, the well-considered and finely-reproduced images, one sleeve after another, each one evoking a pang of need for the old days, a taste of a shot of youth renewed, and if each and every image found herein becomes merely a footnote in the larger historic ledger that envelopes time and remembrance, where the footnotes for those living through them were the heart substance of it all, the pleasures of the postage stamp collection, the row of 19th century half-dollars, the baseball card, that rare CD, that elusive download and, too, whatever comes next. So stop a moment, draw back a bit in time: Pick up Drate’s minor masterpiece here and explore some memories—or, if young, explore the possibilities of the ephemera of a time gone by, alas gone by.

- *Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page

Copyright 2015, Bill Wolf (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter