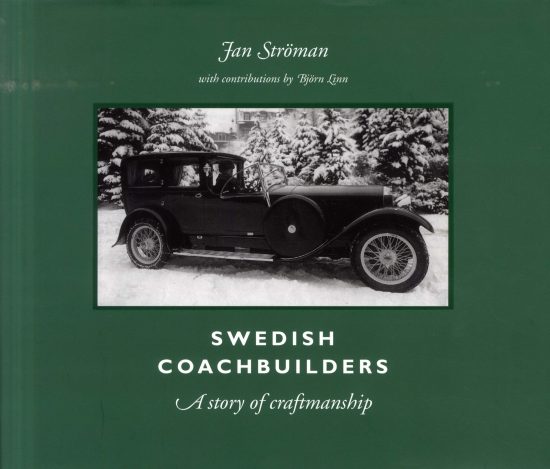

Swedish Coachbuilders – A Story of Craftsmanship

You’d be forgiven for expecting even the definitive work on this subject to be no thicker than, say, “Clarkson on Tact.” Not a bit of it. It begins with a potted social history of motoring in Sweden and a workmanlike romp through the history of coachbuilding by Professor Björn Linn—unusually, highlighting the work of Ernst Neumann (Neander), a neglected maverick of startling originality. The main content is devoted to each coachbuilder in turn, with a page to each design, often with a potted history of the car in question.

As with all good smörgåsbords, it’s a satisfyingly varied selection of the unfamiliar. The coachbuilders’ plates are crisp, and the less formal snaps are justified by the rarity of what they portray. There are also advertisements and posters, various factory shots, and color plates of a few restored cars.

What emerges is a distinctive design vocabulary with two unusual characteristics. The first is what can only be described as a rhinoplastic tendency. The Swedes clearly so liked the swaggering menace of the deep vee prow sported by Benzes and other pre-1914 German marques that their Vagnfabriks fashioned exuberantly pointed pastiches in place of the original manufacturer’s signature radiator—often to caricatural extremes that even the most fervent Crossleyist would find challenging. Good in deep snow, perhaps. At any rate, the Cyrano-like result had an undeniable presence, but like a couturier who has a bash at maxillofacial surgery, it somehow seems impertinent to make an Overland look so much like a K series Isotta. Radless, you can’t tell a Horch from a Hansa…

The other characteristic feature is the panoramic bow-fronted windscreen, of which several are shown between 1914 and the mid-twenties—some one-piece, some two, some three. Another German fad, of course. Was it simply the danger of using large sheets of plate glass in this way that accounted for the disappearance of this strikingly elegant feature for the next couple of decades?

As you will have gathered, the prevailing idiom is Teutonic. Concave curves in the Prinz Heinrich manner abound, and with massively articulated, duvet-padded tops and thickly swaged waistlines, the Swedes’ grammar of the 1930s would have fitted in perfectly Unter den Linden. Also German inspired—this time, by the aerodynamicists of the Stuttgart school—is the streamlined full-width pontoon body for the Venus Bilo, which Nordberg built in 1932 to the design of Gustaf Ericsson (of the telephone family) on a PV655 chassis supplied by Volvo. Clean and well resolved, this pleasingly prescient concept influenced the company’s Airflow-like PV36 Carioca of 1935.

What’s essentially Swedish gradually emerges. There’s a Chevrolet whose owner must have commissioned Norrmalm’s in 1933 to transform his Stovebolt into a simulacrum of Corsica’s thrilling Daimler Double Twelve 50 drophead of two years earlier. That they agreed to try at all is remarkable. Many of the cars are idiosyncratically appointed for exacting owners. The racy “aviation workshop automobile” of 1915, a rakish two-seater Minerva with Nordberg’s snazzy faired-in sidelights, boasted vast storage for parts and lubricants, a compartment for provisions, and a running board washstand. Several others are equipped with transformable beds, which the author soberly assures us were for devotees of exotic long-distance travel rather than the more stereotypically Nordic exertions that baser minds might otherwise assume.

Predictably, many of the names are unfamiliar. Outside Scandinavia, the owner of the Frazer Nash (!) bodied by Hoflageribolaget, for example, must have given the impression of suffering from a speech impediment, if not full-on glossolalia.

Ströman has made excellent use of the archives of the Nordberg (by far the largest player) and Osterman companies and the Swedish Centre for Business History, the publisher. It’s the best book on the subject you’re ever likely to see, and contains many fascinating nuggets. Have a nose.

Copyright 2019, Reg Winstone (speedreaders.info)

This review appears courtesy of the British magazine The Automobile to which Winstone is a contributor.

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter