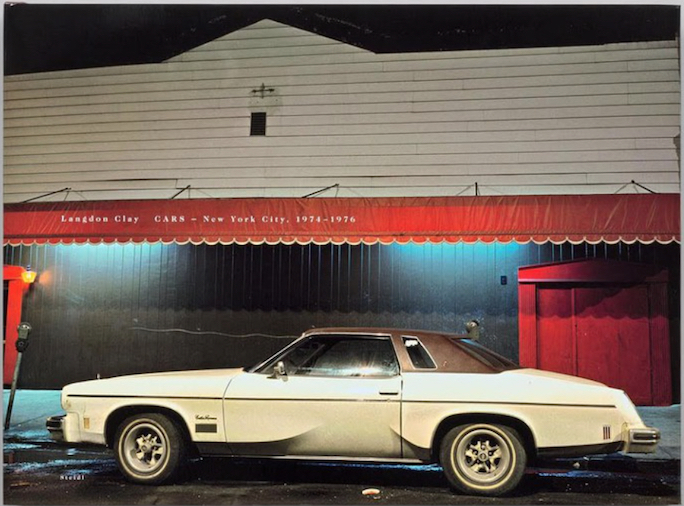

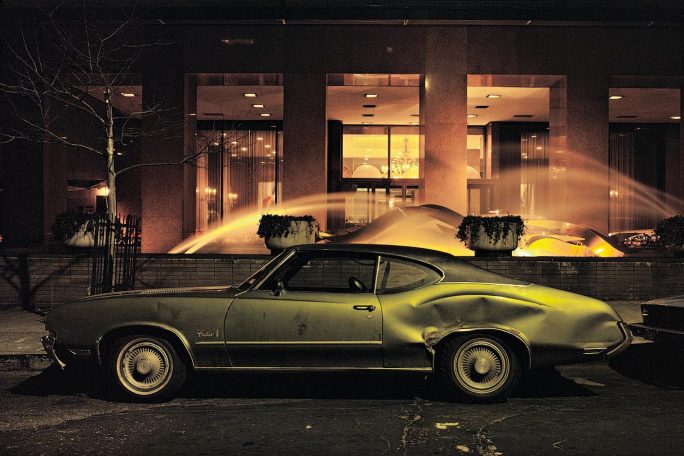

Langdon Clay: Cars – New York City, 1974–1976

by Langdon Clay

“I view the history of photography as a big tree with two main branches—the impressionist branch and the expressionist branch. It is certain that I allied myself then and now with the former. To see what ‘is,’ to record it clearly and to pass it on faithfully to your children and their children and to inquiring Martians and to leave it for posterity, has become my calling. I don’t think I’ve ever wavered in my desire to pull that off, even up to and continuing in the digital era where certain frauds might come easy.”

It helps to have lived in a big city, and at a certain time to appreciate that these are not just any old photos. And it helps to know something about German publisher/printer Steidl to appreciate that this is not just any old book. A Steidl book is a piece of art, or if not art then craft, in its own right regardless of the art it depicts.

If you like photography, if you like bibliophile books, if you like the urban vibe and, not least, if you want to use your dollars to keep art going—Clay shooting, Steidl printing—this book has things to offer you. You do not have to like cars—they are, in this book, props. Or, if you are the cerebral type, placeholders, cyphers. Speaking of dollars, a 20 x 24″ Clay original of a photo in this 12.5 x 8.5″ book starts at $2,200 for a signed and dated archival pigment print.

The book starts with a very intelligent Foreword by Luc Sante. It would make the perfect book review! Of course, it would be neither polite nor legal for us to reprint it so we shall write our own. And we will begin by saying something about Sante because the book does not. Can it really be assumed that the proverbial man in the street would know why him? If you are a New Yorker or read New York-based or -centric publications you may well recognize this Belgian-born (1954) writer and critic as a frequent commentator on all manner of cultural phenomena. The deft word-wrangler also teaches writing and the history of photography, these days at Bard College and, more specific to this book, wrote his own provocative portrayal of the sort of gritty NYC/Manhattan that makes Chamber of Commerce reps groan (Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York, 1991).

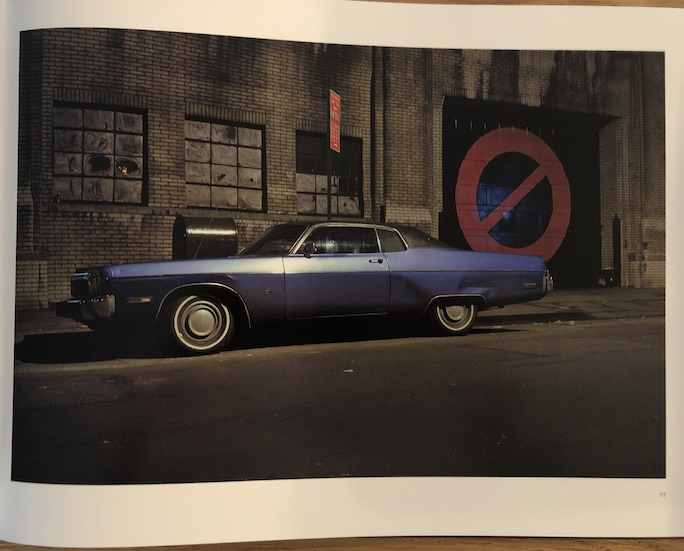

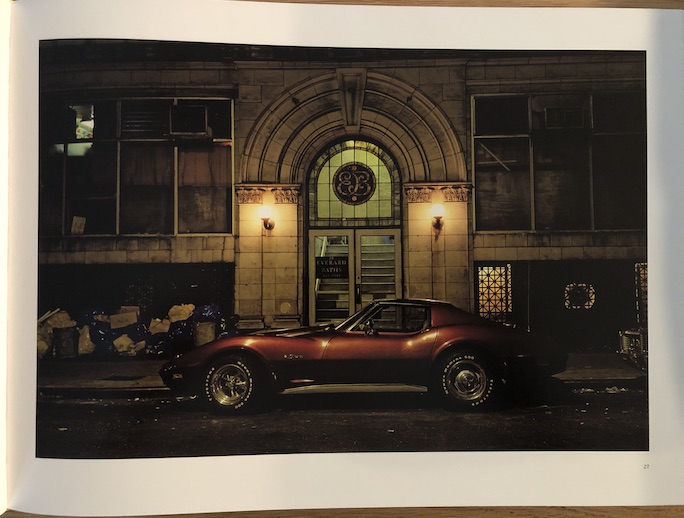

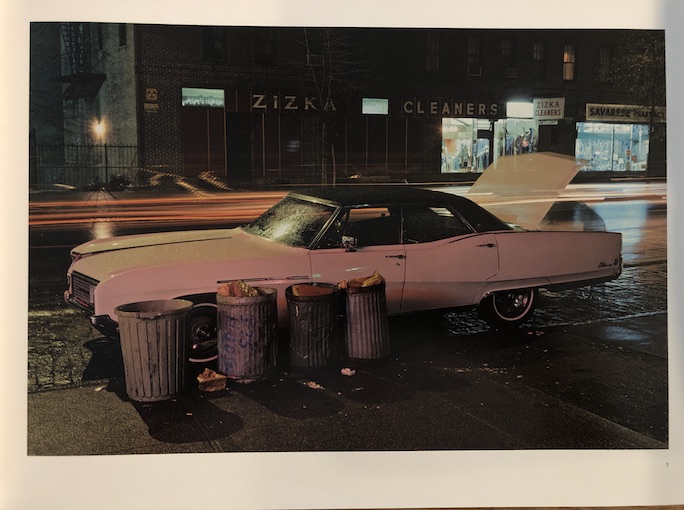

So, yes, him introducing this book is a case of the sighted leading the blind. His first few sentences are so apt that they bear repeating here: “One of the things that used to make America so distinctive was its cars. If you lived there, you would really have to go abroad for a while and then come back to appreciate the difference. In most countries of the world, cars were modest things, little bean-shaped units designed to take two or three people from here to there. In America, cars were real estate.”

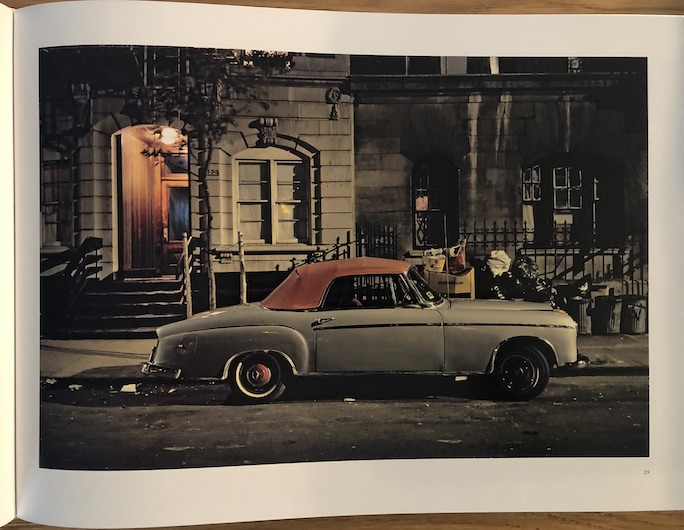

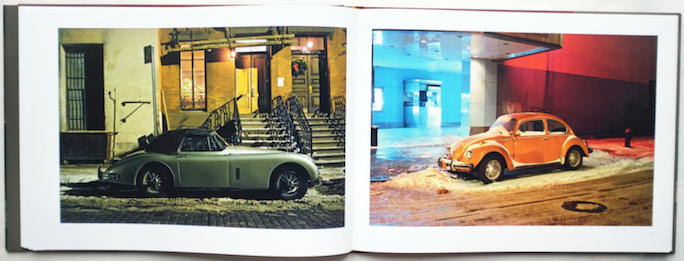

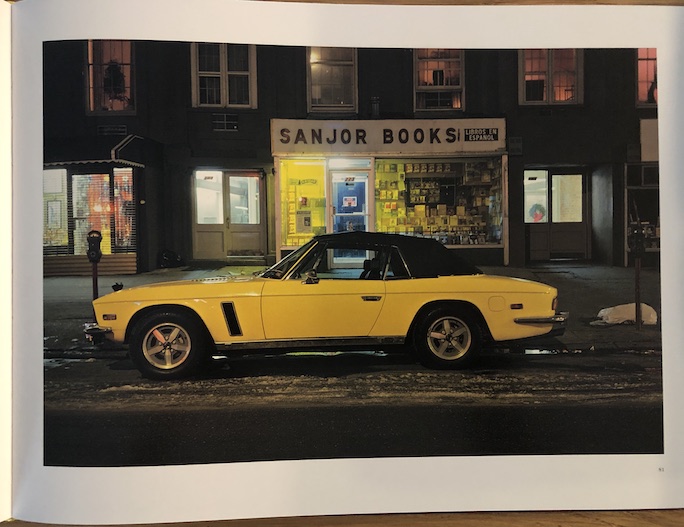

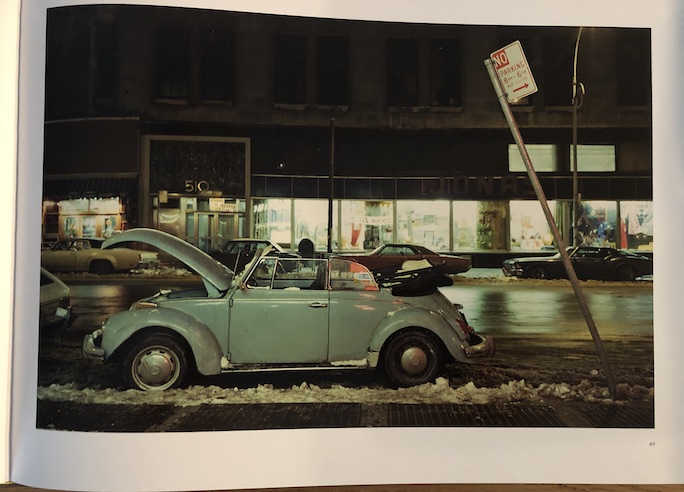

Two European cars. Hardly the bean-shaped pods Sante mentions but his point remains: American land yachts are bigger. The roads are bigger. The parking spaces are bigger. Life is bigger. “In America, cars were real estate. They were enormous boats in which you could eat, sleep, make love, change clothes, throw parties, maintain an office, practice unlicensed dentistry—or take your six best friends out for a spin.” Can’t do that in a Mercedes cabrio, above, or a Jensen, below.

If you read mainstream car mags you might have noticed a 2016 piece by Clay called “Why I Spent Two Years Photographing the Forlorn Cars of New York City” in Road & Track. Turns out that was an adaptation of this book’s Afterword, which you wouldn’t even know was here unless you thumbed through the book ahead of the deep dive (a good habit to develop anyway) as there is no Table of Contents. It contains many useful comments about Clay’s motivation, modus operandi, and technique. The key thought really is the introductory quote above; it actually has a closing sentence, which we omitted—“I wouldn’t say I’ve always succeeded”—because neither the photographer nor a viewer can answer it conclusively.

One wonders what Clay (b. 1949) thinks of the various reviews and essays in photo, car, and culture publications that followed the release of the book and the subsequent gallery shows. None of them have even a fraction of the juice Luc Sante wrings out of his Foreword. To this reviewer, many are utterly trite, regurgitating the press release and wallowing in superficial and beside-the-point imagery such as “the luminous loneliness of an Edward Hopper painting.” Groan. Some compositions have that look, sure, but that was not Clay’s goal nor does it represent his underlying esthetic or organizing principle.

A writer begins with a blank page and imagines, must imagine, what will populate it. A photographer looks through the viewfinder and doesn’t ever see blank space—always there is already something there. A writer can use ten words or a thousand to string a story together; a photographer has one frame to tell a story. Seeing if there’s something there, that’s where the art happens. Moreover, what Clay saw when he clicked the shutter may not at all be what you will see, and what you will see one time will surely not be what you see the next time.

It is interesting to think that young Clay took these photos for no other reason than wanting to do it, honing his craft, learning to speak in color (the last photo in the book is b/w and it is the one that predates all these others), and then shepherded the slides through four decades. Neither the book nor comments by Clay elsewhere explain why the photos are published only now. There obviously exist many more images than the 115 selected for the book.

Superficially, and only superficially, the photos have something in common: all are nighttime shots, which has its own technical challenges and storytelling value. Anyone who looks at these seemingly “simple” photos—car, usually in profile, behind it a building or street—and says “I could do that” is probably quite wrong. And then add the black magic that happens in the darkroom, and the even blacker magic of putting ink on paper . . .

If you have eyes to see, these photos will exercise the imagination. And do seek out Steidl books. Gerhard S. is now 70. After some 50 years in the business his almost monastic dedication to printing and design excellence has earned him the reputation of being—no kidding—the best printer in the world. Just look at the roster of artists who seek to work with him, sometimes waiting for years. That they also, often, come to dread the unwavering, unrelenting attention to detail of the man who lives a few floors above his press and roams the halls at night, is ultimately a compliment. Such perfection does not come cheap but this book was supposed to remain affordable (as indeed quite a few of his books are) and so represents a compromise between the ideal and the realistic. Still, you’ll be spoiled forever.

Oh, a few practical notes: all the photo captions are at the back of the book; they list model of car, location, and year. There are two Bill Collins haikus, one with the first and one with the last image. Only the recto pages have folios.

Copyright 2019, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

Thanks so much for your review of the Cars book.

What I like about what you said is that you are seeing it as a book.

Not a show on walls in a gallery or museum. Not a slide show on a computer or website. But a series of like images with quite specific written stuff. The Europeans would call that value added and try to tax it.

Of course if you’re lucky enough to have Luc Sante in your corner it helps you to sing like a bird.

The next one will be 42nd street of yore. I hope.

Thanks again and Happy New Year, Lang

Thanks! No one’s ever called me a word wrangler before and I like it!

Best wishes for the new year, Luc Sante