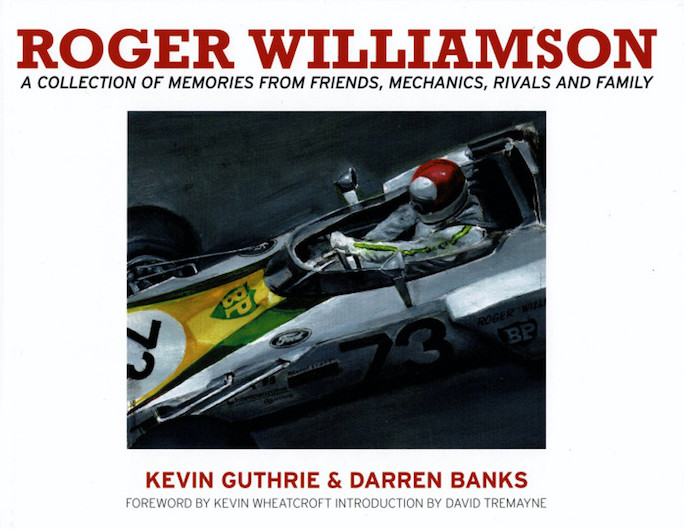

Roger Williamson: A Collection of Memories from Friends, Mechanics, Rivals and Family

by Kevin Guthrie and Darren Banks

“He was the greatest kid I ever knew, and my best racing friend. . . . He was such a character, and I so miss him. I’m looking at a picture of him now.”

—Dave Brodie, friend and fellow racer

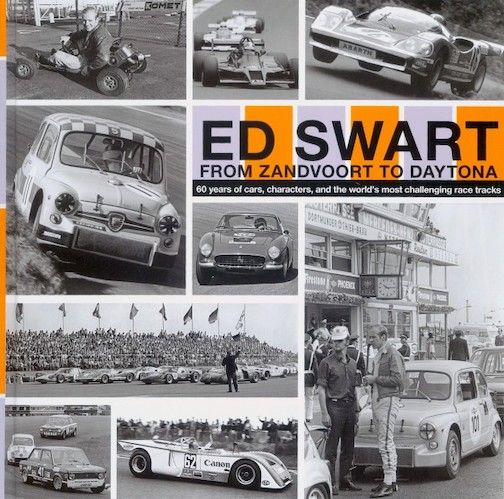

In his 2022 novel, Elizabeth Finch, Julian Barnes suggests there should be a name “for the moment when the last living person to remember you has their very last thought about you.” On the evidence of this lovely book, that moment is still a long time in the future for Roger Williamson, who died at Zandvoort in 1973.

Along with his contemporaries, Tony Brise and Tom Pryce, Williamson (b. 1948) was almost destined to become a successful Grand Prix driver, possibly even a world champion. But not one of that golden trio survived the decade, with Brise dead in Graham Hill’s air crash in late 1975 and Pryce killed at Kyalami in early 1977. They received the requiem they deserved in David Tremayne’s wonderful book The Lost Generation, published in 2006. Such a comprehensive and deeply moving book surely had left nothing unsaid, I had thought, until Messrs Guthrie and Banks wrote their excellent book about Tom Pryce in 2021.

And they have pulled it off again, by enabling those who had known Roger Williamson to share their memories of the gritty racer from Leicester in their own words. This 146-page book contains more than fifty contributions, ranging from a few short paragraphs to several pages of recollections. The fact that Kevin Wheatcroft wrote the Foreword and David Tremayne the Introduction bears witness to the authority of the work.

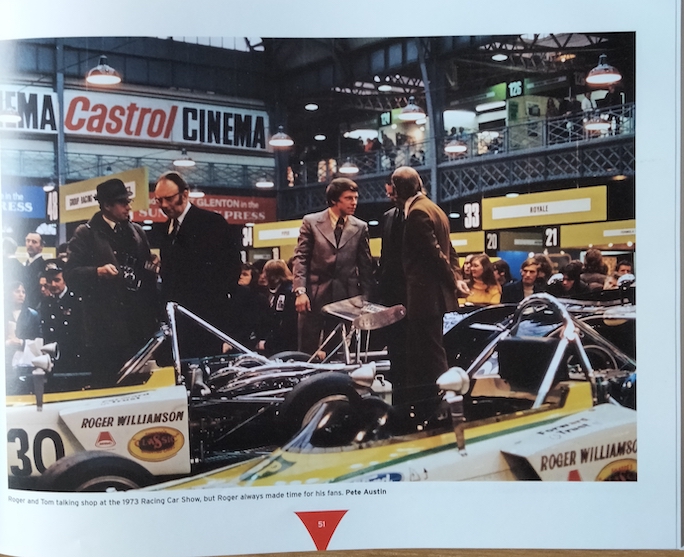

Roger Williamson and Tom Wheatcroft at the 1973 Racing Car Show, London.

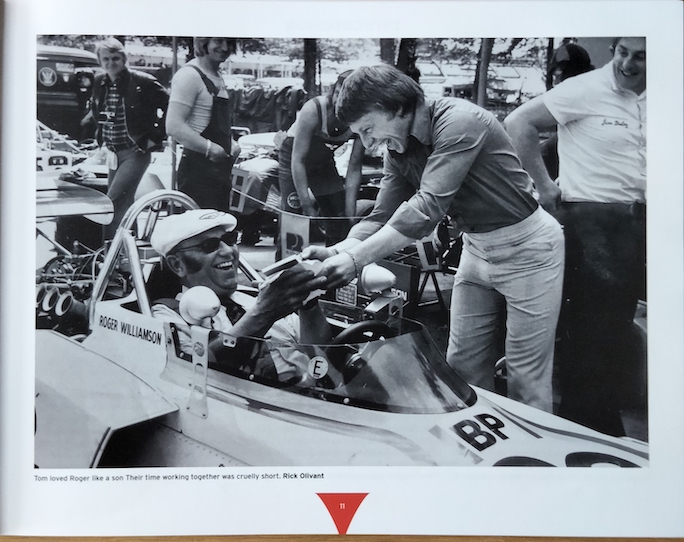

Again, Williamson and Wheatcroft. The caption says: “Tom loved Roger like a son. Their time working together was cruelly short.” There is plenty of period film footage of the crash and its aftermath—but you’ll need a strong stomach to watch it, not least because of the utterly shocking lack of action on the part of marshals who simply stood around listening to Williamson die, leaving fellow driver David Purley who had abandoned his own race in order to help increasingly desperate. He was awarded the George Medal which is granted in recognition of “acts of great bravery.”

Roger Williamson was a naturally talented driver who, having established himself in saloon car racing in a Ford Anglia, effortlessly made the transition to single-seaters; by the early 1970s he was seen as a future Grand Prix star. His reputation as (literally) a head down charger was made in the ferociously competitive arena of British Formula Three, where success almost guaranteed promotion to Formulae Two and then One, if the budgetary stars were in favorable alignment. Half a century ago (Jeez, how did that happen?) I recall motor racing as being a broader church than it is today, and the recollections in the book attest to the diversity of both drivers and their cars. Single-chassis spec formulae were almost unknown then, usually being reserved for novelty races, and drivers came from every stratum of society. Williamson’s contemporary and rival James Hunt’s elevation to Formula One wasn’t exactly hindered by the bullet proof self-confidence assured by an English public school* education. Williamson didn’t have that head start; as journalist Jeremy Walton reflects, “People like Tony Brise had huge talent and family around them. Tom Pryce was hugely talented. Roger was equally talented, but it was combined with sheer hard graft and grit.” And the little details of his personality also enthral—his reported love of the music of Motown made him all the more endearing to this reader.

As we learn from the testimony of friends and family, father figures played a very important role in Williamson’s life. “Dodge” Williamson, Roger’s father, was a self-made small businessman and as hard as nails. As mechanic Andy Dixon laughingly recalled, “I found him a cantankerous old bastard. He was a cranky old bugger!” Dodge supported Roger’s racing until the most important encounter in the latter’s life, when Leicester building magnate Tom Wheatcroft bought Roger a new Holbay F3 engine at Monaco. It has been widely accepted in the racing community that Wheatcroft became effectively a second—or even substitute?—father to Roger and, as Tom’s actual son Kevin recalled, “I felt that my Dad’s bond with Roger got so strong that, two days out of seven, I was losing a Dad.” Jan Neville, a friend of Roger’s, adds her own insight to the theme by remembering how “things changed when Tom took Roger under his wing. You could see the relationship blossoming, Roger really looked up to Tom.”

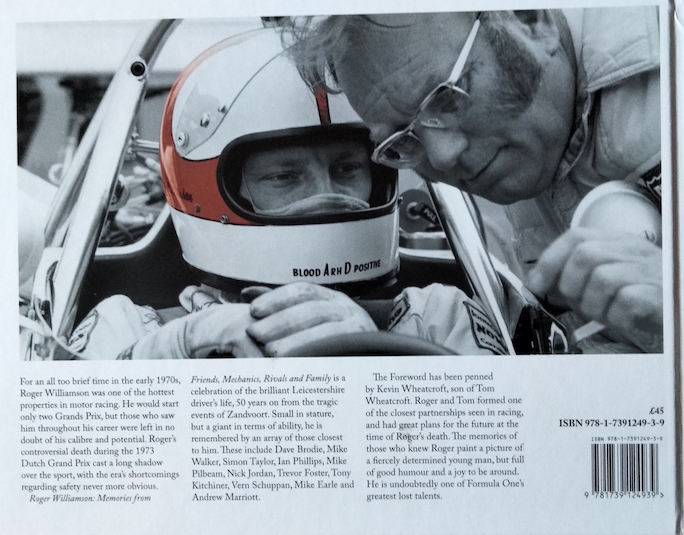

Back cover: note the helmet design; it is repeated in the background to the page numbers.

And maybe Roger’s third father could and should have been Ken Tyrrell; Holbay engine guru Paul Dunnell mentions how Tom Wheatcroft had stated that “it was after watching Roger test for Ken Tyrrell that Jackie Stewart first started thinking about retirement.” It’s possible, I guess, but I suspect that the elevation of François Cevert to the F1 elite, and the mental and physical toll of three world championships, were weighing far heavier in Stewart’s mind. Roger might have driven for Tyrrell, or even stayed with Wheatcroft in one of the two McLaren M23s which Kevin Wheatcroft recalls his father having ordered at the McLaren factory. But what did actually happen to Roger appals even more today than it did in 1973.

The statue commemorating the 30th anniversary of Williamson’s death (Tom Wheatcroft second from L).

Most of the facts are well known about Williamson’s fatal accident at Zandvoort. He had made his Grand Prix debut in the stubby little March 731 at the previous race, at Silverstone, where I had seen him for one lap only, because he fell victim to the huge shunt caused by Jody Scheckter’s mistake at Woodcote. At the next race, the Dutch Grand Prix, Williamson crashed on the eighth lap at Tunnel Oost, and died in the ensuing fire. The book doesn’t shrink from including harrowing testimony on the crash itself from eyewitnesses such as Rob Petersen, and from a host of friends and fellow racers on its aftermath. It is received wisdom that despite David Purley very visibly struggling to turn over a burning car while marshals stood by uselessly and callously, the 18 other drivers still circulating were reportedly unaware of Williamson’s fate. I didn’t believe that then and I don’t believe it now. Race drivers notoriously have acute powers of observation (in the Monaco Grand Prix 1950, Fangio famously noticed the crowd wasn’t looking at him and deduced there was an unseen accident), and it was an era when the show always went on (the 1967 Monaco race continued despite the hideous Lorenzo Bandini crash). Tellingly, Sir Jackie Stewart commented in a recent podcast that the only reason he carried on driving at Zandvoort was that the race had not been stopped. I point no fingers, the past is another country and all that, but this book reminds us graphically not only about the talent that we lost in Roger Williamson, but about how motor racing was once the cruellest sport of them all.

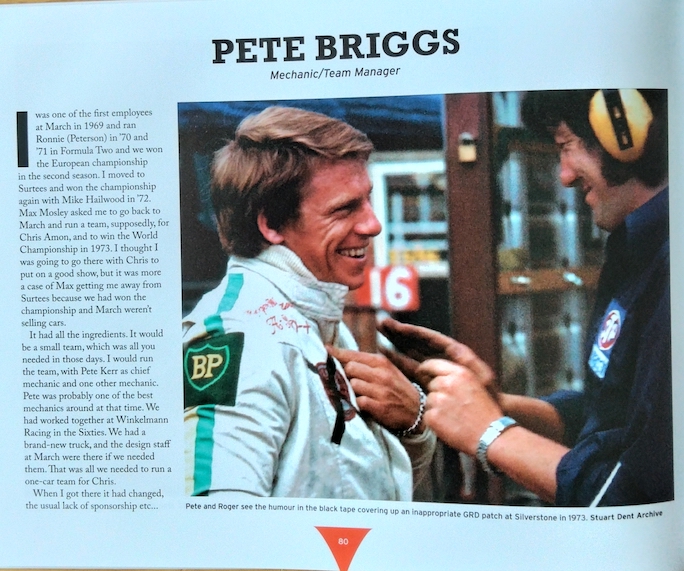

When Williamson made his F1 debut driving for March he first had to have Pete Briggs (r) tape over his previous employer’s logo, the short-lived Group Racing Developments (GRD).

This is not a long book, but its collection of personal memories makes it an absorbing and often moving read. As with the Pryce book, I suspect that the interviews have been reproduced almost verbatim, and doing so adds to their intimacy and authenticity. But as was also the case with the Pryce book, I am bemused why some interviewees felt it was appropriate to punctuate their thoughts with the F word, and with such apparent abandon.

That minor quibble apart, I recommend this book to any student of 1970s Formula One. And I will confess to a wry smile how the page numbers are incorporated into the helmet design of their subject, as they were in the Tom Pryce work. Tony Brise next, I wonder?

- *The English public school equates to an exclusive private school in the USA

Copyright John Aston, 2023 (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter